Stay in the know on all smart updates of your favorite topics.

Mobility and transport are crucial for a city to function properly. Amsterdam is considered the world capital of cycling; 32% of traffic movement in Amsterdam is by bike and 63% of its inhabitants use their bike on daily basis. The number of registered electrical car owners in the Netherlands increased with 53% to 28.889 in 2016. Since 2008 car sharing increased with 376%. However, this is less than 1% of the total car use. Innovative ideas and concepts can help to improve the city’s accessibility, so share your ideas and concepts here.

The impact of the availability of 'self-driving' cars on travel behavior 2/8

If autonomous cars can transport us affordably, do we no longer want to own our own car? Are we switching en masse from public transport, do we leave our bikes unused, or do we walk less? Do we drive alone, or do we share the car with other passengers? Will autonomous cars share he road with other traffic, including cycling? Are we going to use a car more often and longer and how many cars drive empty waiting for a customer?

Of course, no scientific study can answer all these questions yet. Nevertheless, research offers some insight.

Ride-hailing

First, what do we know about the influence of ride-hailing? That is calling a taxi from Uber or Lyft and a handful of other companies with an app. Juniper Research expects that the use of this service, which already has a global turnover of $ 147 billion, will increase fivefold in the coming five years, regardless of whether the taxis involved are 'self -driving' or not. Clear is that most users seem not to appreciate the presence of fellow passengers: the number of travelers that share journeys is only 13%.

Research in seven major American cities shows that 49 to 61 percent of all Uber and Lyft-taxi rides would have been made by walking, cycling, taking public transport or not at all. These journeys only replace car use to a limited extent. As a result, the number of train passengers has already fallen by 1.3% per year and that by bus by 1.7%. At the same time, congestion has increased.

A publication in the Journal Transport policy showed that travelers travel twice as many kilometers in every American region that they would have done if Uber and Lyft did not exist. It also turned out that taxis drive empty 50% of the time while they are waiting for or on their way to a new customer. Another study found that many Uber and Lyft customers who once used public transport buy a car for themselves.

The effect of 'self -driving' cars

The number of studies after the (possible) effect of the arrival of 'self -driving' cars is increasing rapidly. Research by the Boston Consultancy Group showed that 30% of all journeys will take place in a 'self -driving' car as soon as they are available. A considerable number of former public transport users says they will change. Despite the price advantage, the respondents will make little use of the option to share a car with other passengers, but it is known that attitudes and related behavior often differ. Nevertheless, this data has been used to calculate that there will be more cars on the road in large parts of the cities, resulting in more traffic jams.

Semi-experimental research also showed that the ability to travel with a 'self-driving' car results in an increase in the number of kilometers covered by around 60%. Unless autonomous cars drive electrically, this will also have significant negative consequences for the environment.

The Robottaxis in suburbs had a different effect: here travelers would leave their car at home more often and use the taxi to be transported to a station.

See robot taxis and public transport in combination

Despite all the reservations that must be made with this type of research, all results indicate a significant increase in the use of taxis, which will be at the expense of public transport and will result in more traffic jams in urbanized areas. This growth can be reversed by making shared transport more attractive. Especially on the routes to and from train, metro, and bus stations. Only in that case, will there be an ideal transport model for the future: large-scale and fast public transport on the main roads and small-scale public transport for the last kilometers and in rural areas.

In a couple of days my new ebook will be available. It is a collection of the 25 recommendations for better streets, neighbourhoods and city's that have been published at this spot during the last months

1. 'Self-driving' cars: a dream and a nightmare scenario (1/8)

How far are we from large-scale use of 'self-driving' cars. This and subsequent posts deal with this question. In answering it, I will focus on the potential contribution of self-driving cars to the quality of the living environment. Nowadays, the development of self-driving cars has faded a bit into the background. There is a reason for that, and I will get to it later.

When 'self-driving' vehicles first emerged, many believed that a new urban utopia was within reach. This would save millions of lives and contribute to a more livable environment. However, it is only one of the scenarios. Dan Sperling writes: The dream scenario could yield enormous public and private benefits, including greater freedom of choice, greater affordability and accessibility, and healthier, more livable cities, along with reduced greenhouse gas emissions. The nightmare scenario could lead to even further urban expansion, energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions and unhealthy cities and people.

The dream scenario

Do you have to go somewhere? On request, a self-driving car will stop in front of your door within a few minutes to make the desired journey. After you have been safely dropped, the car drives to the next destination. Until a few years ago, companies like Uber and Lync were looking forward to the day when they could fire all their drivers and offer their services with 'self-driving' cars. Naturally at lower prices, which would multiply their customer base. In this scenario, no one wants to have their own car anymore, right? The number of road casualties also will reduce drastically in this scenario. Autonomous cars do not drink, do not drive too fast, never get tired and anticipate unexpected actions of other road users much faster than human drivers. At least that was the argument.

Quick calculations by the proponents of this scenario show that the number of cars needed for passenger transport could decrease by a factor of 20 (!).

The nightmare scenario

This calculation was perhaps a little too fast: Its validity depends on a perfect distribution of all trips over day and night and over the urban space and on the presence of other road users. What you don't want to think about is that outside rush hour, most of the fleet of 'self-driving' cars is stationary somewhere or driving aimlessly in circles. Moreover, the dream scenario assumes that no one switches from public transport, walking, or cycling. Instead of improving cities, these types of cars have the potential to ruin them even further, according to Robin Chase, co-founder of Zipcar. Taxis, especially those from Uber and Lyft, are already contributing to traffic jams in major American cities and to the erosion of public transportation

Both views are based on suspicions, expectations, and extrapolations and a dose of 'wishful thinking' too. In the next posts, I will discuss results of scientific research that allows to form a more informed opinion about both scenarios.

Dit you already visit my new website 'Expeditie Muziek'. This week an exploration of world-class singer-songwriter 'Shania Twain

A new challenge: Floating neighbourhoods with AMS Institute and municipality of Amsterdam

A lot of what we did in Barcelona was about making connections, sharing knowledge, and being inspired. However, we wouldn’t be Amsterdam Smart City if we didn’t give it a bit of our own special flavour. That’s why we decided to take this inspiring opportunity to start a new challenge about floating neighbourhoods together with Anja Reimann (municipality of Amsterdam) and Joke Dufourmont (AMS Institute). The session was hosted at the Microsoft Pavilion.

We are facing many problems right now in the Netherlands. With climate change, flooding and drought are both becoming big problems. We have a big housing shortage and net congestion is becoming a more prominent problem every day. This drove the municipality of Amsterdam and AMS institute to think outside the box when it came to building a new neighbourhood and looking towards all the space we have on the water. Floating neighbourhoods might be the neighbourhoods of the future. In this session, we dived into the challenges and opportunities that this type of neighbourhood can bring.

The session was split up into two parts. The first part was with municipalities and governmental organisations to discuss what a floating neighbourhood would look like. The second part was with entrepreneurs who specialized in mobility to discuss what mobility on and around a floating neighbourhood should look like.

Part one - What should a floating neighbourhood look like?

In this part of the session, we discussed what a floating district should look like:

- What will we do there?

- What will we need there?

- How will we get there?

We discussed by having all the contestants place their answers to these questions on post-its and putting them under the questions. We voted on the post-its to decide what points we found most important.

A few of the answers were:

- One of the key reasons for a person to live in a floating neighbourhood would be to live closer to nature. Making sure that the neighbourhood is in balance with nature is therefore very important.

- We will need space for nature (insects included), modular buildings, and space for living (not just sleeping and working). There need to be recreational spaces, sports fields, theatres and more.

- To get there we would need good infrastructure. If we make a bridge to this neighbourhood should cars be allowed? Or would we prefer foot and bicycle traffic, and, of course, boats? In this group, a carless neighbourhood had the preference, with public boat transfer to travel larger distances.

Part two - How might we organise the mobility system of a floating district?

In the second part of this session, we had a market consultation with mobility experts. We discussed how to organise the mobility system of a floating neighbourhood:

- What are the necessary solutions for achieving this? What are opportunities that are not possible on land and what are the boundaries of what’s possible?

- Which competencies are necessary to achieve this and who has them (which companies)?

- How would we collaborate to achieve this? Is an innovation partnership suitable as a method to work together instead of a public tender? Would you be willing to work with other companies? What business model would work best to collaborate?

We again discussed these questions using the post-it method. After a few minutes of intense writing and putting up post-its we were ready to discuss. There a lot of points so here are only a few of the high lights:

Solutions:

- Local energy: wind, solar, and water energy. There are a lot of opportunities for local energy production on the water because it is often windy, you can generate energy from the water itself, and solar energy is available as well. Battery storage systems are crucial for this.

- Autonomous boats such as the roboat. These can be used for city logistics (parcels) for instance.

- Wireless charging for autonomous ferry’s.

Competencies:

- It should be a pleasant and social place to live in.

- Data needs to be optimized for good city logistics. Shared mobility is a must.

- GPS signal doesn’t work well on water. A solution must be found for this.

- There needs to be a system in place for safety. How would a fire department function on water for instance?

Collaboration:

- Grid operators should be involved. What would the electricity net look like for a floating neighbourhood?

- How do you work together with the mainland? Would you need the mainland or can a floating neighbourhood be self-sufficient?

- We should continue working on this problem on a demo day from Amsterdam Smart City!

A lot more interesting points were raised, and if you are interested in this topic, please reach out to us and get involved. We will continue the conversation around floating neighbourhoods in 2024.

Reflections from the 2023 Smart City Expo

My fifth round at World Smart City Expo in Barcelona brought a blend of familiarity and fresh perspectives. Over the past few years I have grown increasingly skeptical of what I often call “stupid” smart-solutions like surveillance systems, sensored waste bins and digital twins which dominate the Expo. I’ve learned that these solutions often lock cities into proprietary systems and substantial investments with uncertain returns. Amidst this skepticism, I found this year’s activities to be a hub of insightful exchanges and reconnection with international peers. Here's a rundown of my top five learnings and insights from the activities I co-organized or engaged in during the event:

- Generative AI Potential: Visiting the Microsoft Pavilion offered a glimpse into the transforming potential of Generative AI. Microsoft showcased a new product enabling organizations to train their own Generative AI models using internal data, potentially revolutionizing how work gets done. Given the impact we’ve already seen from platforms like OpenAI in the past year, and Microsoft's ongoing investment in this field, it's intriguing to ponder its implications for the future of work.

- BIT Habitat Urban Innovation Approach: I was impressed to learn more about Barcelona’s practical urban innovation approach based on Mariana Mazzucato vision. Every year the city defines a number of challenges and co-finance solutions. Examples of challenges tackled through this program include lowering the number of motorbike accidents, and improving the accessibility of public busses in the city. The aim of the approach is not to develop a new solution, but to find ways to co-finance innovation that generates a public return. This governmental push to shape the market resonates as a much-needed move in the smart city landscape where gains are often privatized while losses are socialized.

- EU Mission: Climate Neutrality and Smart Cities: Discussions at the European Commission’s pavilion with representatives from the NetZeroCities consortium highlighted the need for standardized CO2 monitoring in cities. Currently, methodologies vary widely, making comparisons difficult. Practically this means that one ton of CO2 as calculated in one city might translate to zero or two tons of CO2 in another city. While meeting cities at different stages on their climate journey is crucial (ie some cities might only monitor Scope 1 & 2 emissions, while others will also include Scope 3), a key priority for the European Commission and NetZeroCities should be to implement more standardized and robust approaches for measuring and monitoring CO2 emissions, for instance using satellite data.

- Sustainability & Digitalization Dilemmas: Participating in SmartCitiesWorld’s sustainability roundtable revealed several challenges and dilemmas. A key issue raised by participating cities is that sustainable solutions often benefit only certain segments of the population. Think for instance about the subsides for electric vehicles in your city or country – they most likely flow to the wealthiest portion of the population. Moreover, the assumption that digital and green solutions always complement each other is being challenged, as city representatives are starting to understand that digital solutions can contradict and undermine energy efficiency and neutrality goals. Ultimately many of the participants in the roundtable agree on the need to focus much more on low-tech and behavioral solutions instead of always looking to tech innovations which in many cases are neither affordable, nor effective in achieving their stated goals.

- Drum & Bass Bike Rave: Despite the interesting sessions and conversations, it’s an event outside the Expo that emerged as the highlight for me. Two days before the Expo I joined Dom Whiting’s Drum & Bass On The Bike event, with thousands other people taking to the streets of Barcelona on bikes, roller bladders and skateboards. Whiting first started playing music on his bike to counteract loneliness during the Covid-19 pandemic, and since then he has become a global sensation. This was by far the largest and most special critical mass event I have ever participated, and the collective experience was electrifying. To paraphrase H. G. Wells who is thought to have said that “every time I seem an adult on a bicycle, I no longer despair for the future of the human race”, I can similarly say that seeing thousands of people bike and jam through the streets of Barcelona provided me with a glimpse into a hopeful future where community, sustainability and joy intersect.

Overall, I experienced this edition of the Smart City Expo as a melting pot of diverse perspectives and a valuable opportunity to connect with international peers. However, I do have two perennial critiques and recommendations for next year's event. Firstly, the Dutch delegation should finally organize a "Climate Train" as the main transport for its 300+ delegates to and from the Expo. Secondly, I advocate for a shift in the Expo's focus, prioritizing institutional and policy innovations over the current tech-driven approach. This shift would better address the real challenges cities face and the solutions they need, fulfilling the Expo's ambition to be the platform shaping the future of cities as places we aspire to live in.

CTstreets Map

🚶♀️ How walkable is Amsterdam? 🚶♂️

🏘️ Ever wondered how pedestrian-friendly is your neighbourhood?

Do you feel encouraged and safe to walk in your surroundings?

Do the streets have too much traffic 🚦 and not enough trees 🌳?

I am thrilled to introduce to you the newest sibling of CTwalk: CTstreets Map!

CTstreets is a web tool that highlights how walkable Amsterdam is 🚶♀️ 🚶♂️

It uses openly available data sources and provides information on how walkable neighborhoods, walksheds (5 and 15-minutes), and streets are.

CTstreets was developed through a participatory approach in three main steps:

📖 We studied the literature and made a list of all the factors that are most commonly found to impact walkability.

💬 We asked urban experts who work in Amsterdam to prioritize the identified walkability factors while considering the characteristics and citizens of Amsterdam.

💯 Based on our discussions with the experts we created overall walkability scores, and scores per theme (e.g., related to landscape or proximity) and visualized them.

👀 Explore the web tool here:

CTstreets Map

[currently does not support mobile phones or tablets]

🔍 Learn more about CTstreets Map:

Documentation

On a more personal note, it was wonderful collaborating with Matias Cardoso to develop this project. CTstreets draws significantly from Matia's MSc thesis "Amsterdam on foot," which is openly accessible and you can read here: https://lnkd.in/eyj3dpBZ

Disclaimer:

The estimated walkability scores are heavily based on the availability and quality of existing data sources. The reality is undoubtedly more complex. Walkability can be also personal and the presented scores might not reflect everyone’s point of view. Ctstreets is practically a tool aiming to enable the exploration of factors that impact walkability according to the experts in a simple, interactive, and fun way.

CTwalk Map

What opportunities for social cohesion do cities provide?

Is your neighbourhood park frequented by a homogenous or diverse mix of people? How many hashtag#amenities can you reach within a short hashtag#walking distance? And do you often encounter people from different walks of life?

I am very excited to introduce to you CTwalk Map, a web tool that seeks to highlight the social cohesion potential of neighbourhoods while also unmasking local access hashtag#inequities. CTwalk maps opportunities that different age groups can reach within a 5 or 15-minute walk.

🚶♀️🚶♂️ It uses granular population, location, and pedestrian network data from open sources to estimate how many children, adults, and elderly hashtag#citizens can reach various destinations in a city within a short walk.

🌐 It offers a simple and straightforward understanding of how the 5 and 15-minute walking environments are shaped by the street network.

➗ It estimates the degree of pedestrian co-accessibility of various hashtag#city destinations.

CTwalk Map is now available for the five largest cities in The Netherlands.

Take a look at the web tool:

https://miliasv.github.io/CTwalkMap/?city=amsterdam

... learn more about CTwalk Map at this link:

[currently does not support mobile phones or tablets]

...and let us know what you think!

The Netherlands: country of cars and cows

Last months, 25 facets of the quality of streets, neighbourhoods and cities have been discussed on this spot. But what are the next steps? How urgent is improvement of the quality of the living environment actually?

I fear that the quality of the living environment has been going in the wrong direction for at least half a century and in two respects:

Country of cars

Firstly, the car came to play an increasingly dominant role during that period. Step by step, choices have been made that make traveling by car easier and this has had far-reaching consequences for nature, air quality, climate and environmental planning. Our living environment is designed based on the use of the car instead of what is ecologically possible and desirable for our health. At the same time, public transport is rarely a good alternative, in terms of travel time, costs and punctuality.

Country of cows

A second structural damage to the quality of the living environment comes from the agro-industry. About one half of the surface of our country is intended for cows. These cows make an important contribution to greenhouse gas emissions that further destroy the remaining nature. But this form of land use also leads to inefficient food production, which also results in health problems.

In the next months I will explore two themes: 'Are 'self-driving' cars advantageous ' and the 'The merits of the 15-minute city'. These themes are case studies regarding the quality of the living environment and in both cases mobility and nature play an important role.

After the publication of these two miniseries with zeven posts each, the frequency of my posts on this site will decrease, although I will continue to draw attention on the fundamental choices we have to make regarding environmental issues.

Meanwhile, I started a new blog 'Expeditie Muziek' (in Dutch). I have always neglected my love for music and I am making up for it now. I think readers who love music will enjoy my posts in which pieces of text alternate with YouTube videos as much as I enjoy writing them.

Curious? Visit the link below

Walkability index for Amsterdam 🚶♀️

🚶♀️ How walkable is Amsterdam? 🚶♂️

🏘️ Ever wondered how pedestrian-friendly is your neighbourhood?

Do you feel encouraged and safe to walk in your surroundings?

Do the streets have too much traffic 🚦 and not enough trees 🌳?

Together with Vasileios Milias, we've developed CTstreets map, a new tool where you can check how your street scores in different walkability factors and what might be missing to make it more attractive for pedestrians.

👀 Explore the web tool here: https://miliasv.github.io/CTstreets/?city=amsterdam#15.18/52.371259/4.895385/0/45

🔍 Dive into the methodology and process on our info page: https://miliasv.github.io/CTstreets/info_page/

CTstreets is based on the results of my thesis "Amsterdam on Foot" where I developed a participatory approach to evaluate walkability in every street segment of Amsterdam using open data.

The categories available on the map are Overall walkability, Landscape, Crime Safety, Traffic Safety, Proximity and Infrastructure.

📍 With this tool, you can check how is the walkability per street, neighbourhood or walkshed (5 or 15 minutes) and switch between categories.

A disclaimer about the results presented: While based on the opinions of municipality workers, urban designers and advocates for pedestrian accessibility, this work might not reflect the opinion of everyone. After all, walkability is also influenced by personal factors. Furthermore, the data we used comes from open sources and it might not always be accurate / up to date. Ctstreets aims to enable the exploration of factors that impact walkability according to the experts in a simple, interactive, and fun way, and spark a conversation about how we think and design for pedestrians.

24 Participation

This is the 24st episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Its topic is how involving citizens in policy, beyond the elected representatives, will strengthen democracy and enhance the quality of the living environment, as experienced by citizens.

Strengthening local democracy

Democratization is a decision-making process that identifies the will of the people after which government implements the results. Voting once every few years and subsequently letting an unpredictable coalition of parties make and implement policy is the leanest form of democracy. Democracy can be given more substance along two lines: (1) greater involvement of citizens in policy-making and (2) more autonomy in the performance of tasks. The photos above illustrate these lines; they show citizens who at some stage contribute to policy development, citizens who work on its implementation and citizens who celebrate a success.

Citizen Forums

In Swiss, the desire of citizens for greater involvement in political decision-making at all levels is substantiated by referenda. However, they lack the opportunity to exchange views, let alone to discuss them.

In his book Against Elections (2013), the Flemish political scientist David van Reybrouck proposes appointing representatives based on a weighted lottery. There are several examples in the Netherlands. In most cases, the acceptance of the results by the established politicians, in particular the elected representatives of the people, was the biggest hurdle. A committee led by Alex Brenninkmeijer, who has sadly passed away, has expressed a positive opinion about the role of citizen forums in climate policy in some advice to the House of Representatives. Last year, a mini-citizen's forum was held in Amsterdam, also chaired by Alex Brenninkmeijer, on the concrete question of how Amsterdam can accelerate the energy transition.

Autonomy

The ultimate step towards democratization is autonomy: Residents then not only decide, for example, about playgrounds in their neighbourhood, they also ensure that these are provided, sometimes with financial support from the municipality. The right to do so is formally laid down in the 'right to challenge'. For example, a group of residents proves that they can perform a municipal task better and cheaper themselves. This represents a significant step on the participation ladder from participation to co-creation.

Commons

In Italy, this process has boomed. The city of Bologna is a stronghold of urban commons. Citizens become designers, managers, and users of part of municipal tasks. Ranging from creating green areas, converting an empty house into affordable units for students, the elderly or migrants, operating a minibus service, cleaning and maintaining the city walls, redesigning parts of the public space etcetera.

From 2011 on commons can be given a formal status. In cooperation pacts the city council and the parties involved (informal groups, NGOs, schools, companies) lay down agreements about their activities, responsibilities, and power. Hundreds of pacts have been signed since the regulation was adopted. The city makes available what the citizens need - money, materials, housing, advice - and the citizens donate their time and skills.

From executing together to deciding together

The following types of commons can be distinguished:

Collaboration: Citizens perform projects in their living environment, such as the management of a communal (vegetable) garden, the management of tools to be used jointly, a neighborhood party. The social impact of this kind of activities is large.

Taking over (municipal) tasks: Citizens take care of collective facilities, such as a community center or they manage a previously closed swimming pool. In Bologna, residents have set up a music center in an empty factory with financial support from the municipality.

Cooperation: This refers to a (commercial) activity, for example a group of entrepreneurs who revive a street under their own responsibility.

Self-government: The municipality delegates several administrative and management tasks to the residents of a neighborhood after they have drawn up a plan, for example for the maintenance of green areas, taking care of shared facilities, the operation of minibus transport.

<em>Budgetting</em>: In a growing number of cities, citizens jointly develop proposals to spend part of the municipal budget.

The role of the municipality in local initiatives

The success of commons in Italy and elsewhere in the world – think of the Dutch energy cooperatives – is based on people’s desire to perform a task of mutual benefit together, but also on the availability of resources and support.

The way support is organized is an important success factor. The placemaking model, developed in the United Kingdom, can be applied on a large scale. In this model, small independent support teams at neighbourhood level have proven to be necessary and effective.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

22. Nature, never far away

This is the 22st episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Its topic is the way how the quality of the living environment benefits from reducing the contrast between urban and rural areas.

Photos from space show a sharp contrast between city and countryside. Urban areas are predominantly gray; rural areas turn green, yellow, and brown, but sharp contrasts are also visible within cities between densely built-up neighborhoods and parks. Even between neighborhoods there are sometimes sharp transitions.

The division between city and country

Large and medium-sized cities on the one hand and rural areas on the other are worlds apart in many respects and local government in municipalities would like to keep it that way. For a balanced development of urban and rural areas, it is much better if mutual cohesion is emphasized, that their development takes place from a single spatial vision and (administrative) organization and that there are smooth transitions between both. The biggest mistake one can made is regarding the contrast between city and country as a contradiction between city and nature. Where large-scale agriculture predominates in the rural area, the remaining nature has a hard time. Where nature-inclusive construction takes place in cities, biodiversity is visibly increasing.

The idea that urban and rural areas should interpenetrate each other is not new. At the time, in Amsterdam it was decided to retain several wedges and to build garden villages. Some of the images in the above collage show such smooth transitions between urban and rural areas: Eko Park, Sweden (top right), Abuja, Nigeria (bottom left), and Xion'an, China (bottom center). The latter two are designs by SOM, an international urban design agency that focuses on biophilic designs.

Pulling nature into the city

Marian Stuiver is program leader Green Cities of Wageningen Environmental Research at WUR. In her just-released book The Symbiotic City, she describes the need to re-embed cities in soil, water and living organisms. An interesting example is a design by two of her students, Piels and Çiftçi, for the urban expansion of Lelystad. The surrounding nature continues into the built-up area: soil and existing waterways are leading; buildings have been adapted accordingly. Passages for animals run between and under the houses (see photo collage, top left). Others speak of rewilding. In this context, there is no objection to a small part of the countryside being given a residential destination. Nature benefits!

Restoration of the rural area

The threat to nature does not come from urban expansion in the first place, but mainly from the expansion of the agricultural area. Don't just think immediately of the clearing of tropical rain woods to produce palm oil. About half of the Dutch land area is intended for cows. Usually, most of them are stabled and the land is mainly used to produce animal feed.

The development of large-scale industrialized agriculture has led to the disappearance of most small landscape features, one of the causes of declining biodiversity. Part of the Climate Agreement on 28 June 2019 was the intention to draw up the Aanvalsplan landschapselementen . Many over-fertilized meadows and fields that are intended to produce animal feed in the Netherlands were once valuable nature reserves. Today they value from a biodiversity point of view is restricted and they are a source of greenhouse gases. Nature restoration is therefore not primarily focusses at increasing the wooded area. Most of the land can continue to be used for agricultural and livestock farming, provided that it is operated in a nature-inclusive manner. The number of farmers will then increase rather than decrease.

Pulling the city into nature

There are no objections against densification of the city as long this respects the green area within the city. So-called vertical forests by no means make up for the loss of greenery. Moreover, space is needed for urban agriculture and horticulture (photo collage, top center), offices, crafts, and clean industry as part of the pursuit of complete districts. Nature in the Netherlands benefits if one to two percent of the land that is currently used to produce animal feed is used for housing, embedded in a green-blue infrastructure. Some expansion and densification also apply to villages, which as a result are once again developing support for the facilities, they saw disappearing in recent decades.

Finally, I mentioned earlier that nature is more than water, soils, plants, and trees. Biophilic architects also draw nature into the built environment by incorporating analogies with natural forms into the design and using natural processes for cooling and healthy air. The 'Zandkasteel' in Amsterdam is still an iconic example (photo collage, bottom right).

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

21. Work, also in the neighbourhood

This is the 21th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Its topic is the combination of living and working in the same neighbourhood. This idea is currently high on the agenda of many city councils.

Benefits for the quality of the living environment

If there is also employment in or near the place where people live, several residents might walk to work. That will only apply to relatively few people, but urban planners think that bringing living and working closer together will also increase the liveliness of the neighborhood. But more reasons are mentioned: including cross-fertilization, sharing of spaces, the shared use of infrastructure (over time), a greater sense of security and less crime. Whether all these reasons are substantiated is doubtful.

In any case, mixed neighbourhoods contributes to widening the range of residential environments and there is certainly a group that finds this an attractive idea. The illustrations above show places were living and work will be mixed (clockwise): Deventer (Havenkwartier), The Hague (Blinckhorst), Leiden (Bioscience Park), Amersfoort (Oliemolenterrein), Amsterdam (Ravel) and Hilversum (Wybertjesfabriek).

Break with the past

Le Corbusier detested the geographical nearness of work and living. In his vision, all the daily necessities of residents of the vertical villages he had in mind had to be close to home, but the distance to work locations could not be great enough. Incidentally, very understandable because of the polluting nature of the industry in the first half of the 20th century. Nowadays, the latter is less valid. An estimated 30% of companies located on industrial sites have no negative environmental impact whatsoever. A location in a residential area therefore does not have to encounter any objections. The choice for an industrial site was mainly dictated because the land there is much cheaper. And that's where the shoe pinches. The most important reason to look for housing locations on industrial estates is the scarcity of residential locations within the municipality and consequently their high prices. Moreover, in recent decades the surface of industrial estates has grown faster than that of residential locations, at least until a couple of years ago.

Companies are still hesitating

Companies are generally reserved about the development of housing in their immediate vicinity. Apart from the realistic expectation that the price of land will rise, they fear that this will be at the expense of space that they think they will need to grow in the future. This fear is justified: In the Netherlands 4600 hectares of potential commercial sites disappeared between 2016 and 2021. Another concern is that future 'neighbors' will protest against the 'nuisance' that is inherent to industrial sites, among others because of the traffic they attract. The degree of 'nuisance' will mainly depend on the scale on which the mixing will take place. If this happens at block level, the risk is higher than in case of the establishment of residential neighborhoods in a commercial environment. But as said, there is no need to fear substantial nuisance from offices, laboratories, call centers and the like. Companies also see the advantages of mixing living and working, such as more security.

Searching for attractive combinations of living and working

Project developers see demand for mixed-use spaces rising and so do prices, which is an incentive for the construction of compact multifunctional buildings, in which functions are combined. To create sufficient space for business activity in the future, they advocate reserving 30% for business space in all residential locations. The municipality of Rotterdam counters this with a 'no net loss' policy regarding gross floor surface for commercial spaces.

Gradually, attractive examples of mixed living and working areas emerge. Park More (from Thomas More), the entrance area of the Leiden Bioscience Park, which will consist of homes, university facilities and a hotel (photo top right). The idea is that in the future there will also be room for the storage of rainwater, the cultivation of food and the production of the estate's own energy.

Another example, which can probably be followed in more places, is the transformation of the Havenkwartier Deventer into a mixed residential and working area, although part of the commercial activity has left and the buildings are being repurposed as industrial heritage (photo above left). The starting point is that, despite hundreds of new homes, the area will retain its industrial and commercial character, although some residents complain about the 'smoothening' of the area'. Living and working remains a challenging combination, partly depending on where the emphasis lies. In this respect, many eyes are focused on the substantiation of the plans of Amsterdam Havenstad.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

20. Facilities within walking and cycling distance

This is the 20th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Its topic is to enable citizens having daily necessities in a walking and bicycling distance.

During the pandemic, lockdowns prevented people from leaving their homes or moving over a longer distance. Many citizens rediscovered their own neighbourhood. They visited the parks every day, the turnover of the local shops increased, and commuters suddenly had much more time. Despite all the concerns, the pandemic contributed to a revival of a village-like sociability.

Revival of the ‘whole neighbourhood’

Revival indeed, because until the 1960s, most residents of cities in Europe, the US, Canada, and Australia did not know better than their dally needs were available within a few minutes' walk. In the street where I was born, there were four butchers, four bakers, three greengrocers and four groceries, even though the street was not much longer than 500 meters. No single shop survived. My primary school was also on that street, and you had to be around the corner for the doctor. This type of quality of life went lost, in the USA in particular. However, urban planners never have forgotten this idea. In many cities, the pandemic has turned these memories into attainable goals, albeit still far removed from reality. Nevertheless, the idea of the 'whole neighborhood' gained traction in many cities. It fits into a more comprehensive planning concept, the 15-minute city.

Support for facilities

The idea is that residents can find all daily needs within an imaginary circle with an area of approximately 50 hectares. This implies a proportionate number of residents. A lower limit of 150 residents per hectare is often mentioned, considering a floor area of 40% for offices and small industry. The idea is further that most streets are car-free and provide plenty of opportunity for play and meeting.

Opportunity for social contacts

In a 'whole neighbourhood', residents find opportunity for shopping and meeting from morning to evening. There is a supermarket, a bakery, a butcher, a greengrocer's shop, a drugstore, a handful of cafes and restaurants, a fitness center, a primary school, a medical center, craft workshops, offices, green spaces and a wide variety of houses. Here, people who work at home drink their morning coffee, employees meet colleagues and freelancers work at a café table during the quiet hours. Housemen and women do their daily shopping or work out in the gym, have a chat, and drink a cup of tea. People meet for lunch, dinner and socializing on the terrace or in the cafes, until closing time. A good example is the Oostpoort in Amsterdam, albeit one of the larger ones with a station and a few tram lines.

Planning model

On the map above, the boundaries of the neighborhoods with an area of approximately 50 hectares are shown in the form of circles. The circular neighborhood is a model. This principle can already play a role on the drawing board in new neighborhoods to be built. In existing neighbourhoods, drawing circles is mainly a matter of considering local data. The center of the circle will then often be placed where there are already some shops. Shops outside the intended central area can be helped to move to this area. Spaces between existing homes can be reserved for small-scale businesses, schools, small parks, communal gardens and play facilities. Once the contours have been established, densification can be implemented by choosing housing designs that align to the character of the neighbourhood. Towards the outside of the imaginary circle, the building density will decrease, except at public transport stops or where circles border the water, often an ideal place for higher buildings.

If a thoroughfare passes through the center of the circle, this street can be developed into a city street, including a public transport route. Facilities are then realized around a small square in the center of the circle and the surrounding streets.

Incidentally, space between the circles can be used for through traffic, parks, and facilities that transcend districts, for instance a swimming pool or a sports hall or an underground parking garage. Mostly, neighborhoods will merge seamlessly into each other.

It will take time before this dream comes true.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

19. Safe living environment

This is the 19th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. This post is about increasing the independent mobility of children and the elderly, which is limited due to the dangers that traffic entails.

For safety reasons, most urban children under the age of ten are taken to school. The same goes for most other destinations nearby. It hampers children’s independent mobility, which is important for their development.

Car-free routes for pedestrians and cyclists

For security reasons, car-free connections between homes and schools, community centers, bus stops and other facilities are mandatory (photo’s top left and bottom right). Car routes, in their turn, head to neighborhood parking spaces or underground parking garages. Except for a limited number of parking spaces for disabled people.

Design rules

Model-wise, the design of a residential area consists of quadrants of approximately 200 x 200 meters in which connections are primarily intended for pedestrians and cyclists. There are routes for motorized traffic between the quadrants and there are parking facilities and bus stops at the edges. Inhabitants might decide that cars may enter the pedestrian area at walking pace to load and unload to disappear immediately afterwards. The routes for pedestrians and cyclists connect directly with the shops and other destinations in the neighborhood, based on the idea of the 15-minute city. Shops 'ideally' serve 9 to 16 quadrants. In practice, this mode will have many variations because of terrain characteristics, building types and aesthetic considerations.

Examples

The number of neighborhoods where cars can only park on the outskirts is growing. A classic example is 'ecological paradise' Vauban were 50 'Baugruppen' (housing cooperatives) have provided affordable housing (photo bottom middle ). Car-free too is the former site of the Gemeentelijk waterleidingbedrijf municipal water supply company in Amsterdam - (photo bottom left). Here almost all homes have a garden, roof terrace or spacious balcony. The Merwede district in Utrecht (top middle) will have 12,000 inhabitants and for only 30% room for parking is available, and even then only on the edge of the district. Shared cars, on the other hand, will be widely available. The space between the houses is intended for pedestrians, cyclists and children playing.

More emphasis on collective green

Due to the separation of traffic types and the absence of nuisance caused by car, there are no obligatory streets, but wide foot- and cycle paths. Instead there are large lawns for playing and picnicking, vegetable gardens and playgrounds. Further space savings will be achieved by limiting the depth of the front and back gardens. Instead, large collective space appears between the residential blocks; remember the Rivierenwijk in Utrecht that I mentioned in the former post (top right). Behind the buildings, there is room for small backyards, storage sheds and possibly parking space.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

18. Space for sporting and playing in a green environment

This is the 18th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. This message is about the limited possibilities for children to play in a green environment because of the sacrifices that are made to offer space for cars and private gardens

Almost all residential areas in the Netherlands offer too little opportunity for children to play. This post deals with this topic and also with changing the classic street pattern to make way for routes for pedestrians and cyclists.

Everything previously mentioned about the value of a green space applies to the living environment. The rule 3 : 30 : 300 is often used as an ideal: Three trees must be visible from every house, the canopy cover of the neighborhood is 30% and within an average distance of 300 meters there is a quarter of a hectare of green space, whether or not divided over a number of smaller parcels.

Functions of 'green' in neighbourhoods

The green space in the living environment must be more than a grass cover. Instead, it creates a park-like environment where people meet, it is accompanied by water features and can store water in case of superfluent rain, it limits the temperature and forms the basis for play areas for children.

Legally, communal, and private green areas are different entities; in practice, hybrid forms are becoming common. For example, a communal (inner) garden that can be closed off in the evening or public green that is cadastral property of the residents but intended for public use. In that case the residents live in a park-like environment which they might maintain and use together. Het Rivierdistrict in Utrecht is an example of this.

Play at the neighborhood level

Children want wide sidewalks and a place (at least 20 x 10 m2) close to home that is suitable for (fantasy) games and where there may also be attractive play equipment. The importance of playground equipment should not be overestimated. For many children, the ideal playground consists of heaps of coarse sand, water, climbing trees and pallets. To the local residents It undoubtedly looks messier than a field full of seesaw chickens. Good playground equipment is of course safe and encourages creative action. They can also be used for more than one purpose. You can climb on it, slide off it, play hide and seek and more. Of the simple devices, (saucer) swings and climbing frames are favorites.

A somewhat larger playground to play football and practice other sports is highly regarded. Such a space attracts many children from the surrounding streets and leads to the children playing with each other in varying combinations.

Squares

Most squares are large bare plains, which you prefer to walk around. Every neighborhood should have a square of considerable size as a place where various forms of play and exercise are concentrated. In the middle there is room for a multifunctional space - tastefully tiled or equipped with (artificial) grass - for ball games, events, music performances, markets and possibly movable benches. Ideally, the central part is somewhat lower, so that there is a slope to sit on, climb and slide down. On the edge there is room for countless activities, such as different forms of ball games, a rough part, with climbing trees, meeting places, spaces to hide, space to barbecue and walls to paint, but also catering and one or more terraces. Lighting is desirable in the evening, possibly (coloured) mood lighting. There is an opportunity for unexpected and unforeseen activities, such as a food car that comes by regularly, street musicians that come to visit, changing fairground attractions and a salsa band that comes to rehearse every week.

Such a square can possibly be integrated into a park that, apart from its value as a green space, already offers opportunities for children to play. Adding explicit game elements makes parks even more attractive.

Connecting car-free routes

Safe walking and cycling routes connect playgrounds, parks, and homes. They offer excellent opportunities to use bicycles, especially where they are connected to those of other neighbourhoods.

By seeing facilities for different age groups in conjunction, networks and nodes are created for distinctive target groups. The children's network mainly includes play areas close to home, connected via safe paths to playgrounds in the vicinity. Facilities especially for teenagers are best located somewhat secluded, but not isolated. Essentially, they want to fit in. The teenage network also includes places where there is something to eat, but also various facilities for sports and at a certain age it includes the entire municipality.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

17. A sociable inclusive neighborhood

This is the 17th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. This post is about the contributions of sociability and inclusivity to the quality of the living environment.

Almost everyone who is going to move looks forward with some trepidation to who the neighbors will be. This post is about similarities and differences between residents as the basis for a sociable end inclusive neighborhood.

"Our kind of people"

The question 'what do you hope your neighbors are' is often answered spontaneously with 'our kind of people'. There is a practical side to this: a family with children hopes for a family with playmates of about the same age. But also, that the neighbors are not too noisy, that they are in for a pleasant contact or for making practical arrangements, bearing in mind the principle 'a good neighbor is better than a distant friend'. A person with poor understanding often interprets 'our kind of people' as people with the same income, religion, ethnic or cultural background. That doesn't have to be the case. On the other hand, nothing is wrong if people with similar identities seeking each other's proximity on a small scale.

All kinds of people

A certain homogeneity among the immediate neighbours, say those in the same building block, can go hand in hand with a greater variety at the neighbourhood level in terms of lifestyle, ethnic or cultural background, age, and capacity. This variety is a prerequisite for the growth of inclusiveness. Not everyone will interact with everyone, but diversity in ideas, interests and capacities can come in handy when organizing joint activities at neighborhood and district level.

Variation in living and living arrangements

The presence of a variety in lifestyles and living arrangements can be inspiring. For example, cohousing projects sometimes have facilities such as a fitness center or a restaurant that are accessible to other residents in the neighbourhood. The same applies to a cohabitation project for the elderly. But it is also conceivable that there is a project in the area for assisted living for (former) drug addicts or former homeless people. The Actieagenda Wonen “Samen werken aan goed wonen” (2021) provides examples of the new mantra 'the inclusive neighbourhood'. It is a hopeful story in a dossier in which misery predominates. The Majella Wonen project in Utrecht appealed to me: Two post-war apartment complexes have been converted into a place where former homeless people and 'regular' tenants have developed a close-knit community. It benefits everyone if the residents of these types of projects are accepted in the neighborhood and invited to participate.

Consultation between neighbours

It remains important that residents as early as possible discuss agreements about how the shared part of life can be made as pleasant as possible. This is best done through varying combinations of informal neighborhood representatives who discuss current affairs with their immediate neighbours. A Whatsapp group is indispensable.

Mixing income groups is also desirable, especially if the differences in housing and garden size are not too great. It does not work if the impression of a kind of 'gold coast' is created.

If functions are mixed and there are also offices and other forms of activity in a neighborhood, it is desirable that employees also integrate. This will almost happen automatically if there is a community center with catering.

Most of what is mentioned above, cannot be planned, but a dose of goodwill on the part of all those involved contributes to the best quality of living together.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

16. A pleasant (family) home

This is the 16th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. This post is about one of the most important contributions to the quality of the living environment, a pleasant (family)home.

It is generally assumed that parents with children prefer a single-family home. New construction of this kind of dwelling units in urban areas will be limited due to the scarcity of land. Moreover, there are potentially enough ground-access homes in the Netherlands. Hundreds of thousands have been built in recent decades, while families with children, for whom this type of housing was intended, only use 25% of the available housing stock. In addition, many ground-access homes will become available in the coming years, if the elderly can move on to more suitable housing.

The stacked house of your dreams

It is expected that urban buildings will mainly be built in stacks. Stacked living in higher densities than is currently the case can contribute to the preservation of green space and create economic support for facilities at neighbourhood level. In view of the differing wishes of those who will be using stacked housing, a wide variation of the range is necessary. The main question that arises is what does a stacked house look like that is also attractive for families with children?

Area developer BPD (Bouwfonds Property Development) studied the housing needs of urban families based on desk research, surveys and group discussions with parents and children who already live in the city and formulated guidelines for the design of 'child-friendly' homes based on this.

Another source of ideas for attractive stacked construction was the competition to design the most child-friendly apartment in Rotterdam. The winning design would be realized. An analysis of the entries shows that flexible floor plans stand head and shoulders above other wishes. This wish was mentioned no less than 104×. Other remarkably common wishes are collective outdoor space [68×], each child their own place/play area [55×], bicycle shed [43×], roof garden [40×], vertical street [28×], peace and privacy [27× ], extra storage space [26×], excess [22×] and a spacious entrance [17×].

Flexible layout

One of the most expressed wishes is a flexible layout. Family circumstances change regularly and then residents want to be able to 'translate' to the layout without having to move. That is why a fixed 'wet unit' is often provided and wall and door systems as well as floor coverings are movable. It even happens that non-load-bearing partition walls between apartments can be moved.

Phased transition from public to private space

One of the objections to stacked living is the presence of anonymous spaces, such as galleries, stairwells, storerooms, and elevators. Sometimes children use these as a play area for lack of anything better. To put an end to this kind of no man's land, clusters of 10 – 15 residential units with a shared stairwell are created. This solution appeals to what Oscar Newman calls a defensible space, which mainly concerns social control, surveillance, territoriality, image, management, and sense of ownership. These 'neighborhoods' then form a transition zone between the own apartment, the rest of the building and the outside world, in which the residents feel familiar. Adults indicate that the use of shared cars should also be organized in these types of clusters.

Variation

Once, as the housing market becomes less overburdened, home seekers will have more options. These relate to the nature of the house (ground floor or stacked) and - related thereto - the price, the location (central or more peripheral) and the nature of the apartment itself. But also, on the presence of communal facilities in general and for children in particular.

Many families with children prefer that their neighbors are in the same phase of life and that the children are of a similar age. In addition, they prefer an apartment on the ground floor or lower floors that preferably consists of two floors.

Communal facilities

Communal facilities vary in nature and size. Such facilities contain much more than a stairwell, lift and bicycle storage. This includes washing and drying rooms, hobby rooms, opportunities for indoor and outdoor play, including a football cage on the roof and inner gardens. Houses intended for cohousing will also have a communal lounge area and even a catering facility.

However, the communal facilities lead to a considerable increase in costs. That is why motivated resident groups are looking for other solutions.

Building collectively or cooperatively

The need for new buildings will increasingly be met by cooperative or collective construction. Many municipalities encourage this, but these are complicated processes, the result of which is usually a home that better meets the needs at a relatively low price and where people have got to know the co-residents well in advance.

With cooperative construction, the intended residents own the entire building and rent a housing unit, which also makes this form of housing accessible to lower incomes. With collective building, there is an association of owners, and everyone owns their own apartment.

Indoor and outdoor space for each residential unit

Apartments must have sufficient indoor and outdoor space. The size of the interior space will differ depending on price, location and need and the nature of the shared facilities. If the latter are limited, it is usually assumed that 40 - 60 m2 for a single-person household, 60 - 100 m2 for two persons and 80 - 120 m2 for a three-person household. For each resident more about 15 to 20 m2 extra. Children over 8 have their own space. In addition, more and more requirements are being set for the presence, size, and safety of a balcony, preferably (partly) covered. The smallest children must be able to play there, and the family must be able to use it as a dining area. There must also be some protection against the wind.

Residents of family apartments also want their apartment to have a spacious hall, which can also be used as a play area, plenty of storage space and good sound insulation.

'The Babylon' in Rotterdam

De Babel is the winning entry of the competition mentioned before to design the ideal family-friendly stacked home (see title image). The building contains 24 family homes. All apartments are connected on the outside by stairs and wide galleries. As a result, there are opportunities for meeting and playing on all floors. The building is a kind of box construction that tapers from wide to narrow. The resulting terraces are a combination of communal and private spaces. Due to the stacked design, each house has its own shape and layout. The living areas vary between approximately 80 m2 and 155 m2 and a penthouse of 190 m2. Dimensions and layouts of the houses are flexible. Prices range from €400,000 – €1,145,000 including a parking space (price level 2021).

As promised, the building has now been completed, albeit in a considerably 'skimmed-down' form compared to the 'playful' design (left), no doubt for cost reasons. The enclosed stairs that were originally planned have been replaced by external steel structures that will not please everyone. Anyway, it is an attractive edifice.

15. Affordable housing

This is the 15th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. This post is about one of the most serious threats to the quality of the living environment, namely the scarcity of housing, which is also unaffordable for many.

In many countries, adequate housing has become scarcer and too expensive for an increasing number of people. Unfortunately, government policy plays an important role in this. But good policy can also bring about a change. That's what this post is about.

As in many other developed countries, for a large part of the 20th century, the Dutch government considered it as its task to provide lower and middle classes with good and affordable housing. Housing associations ensured the implementation of this policy. Add to this well-equipped neighborhood shopping centers, ample medical, social, educational and transportation facilities and a diverse population. When the housing shortage eased in the 1970s, the nation was happier than ever. That didn't take long.

The emergence of market thinking in housing policy

During the last decades of the 20th century, the concern for housing largely shifted to the market. Parallel to this, housing corporations had to sell part of their housing stock. Mortgages were in easy reach and various tax facilities, such as the 'jubelton' and the mortgage interest deduction, brought an owner-occupied home within reach of many. In contrast, the waiting time for affordable rental housing increased to more than 10 years and rental housing in the liberalized zone became increasingly scarce and expensive. In Germany and Austria, providing good housing has remained a high priority for the government and waiting times are much shorter. The photo at the top left part shows the famous housing project Alt Erla in Vienna. Bottom shows left six affordable homes on the surface of one former home in an American suburb and top right is the 'Kolenkit', a social housing project in Amsterdam.

The explosive rise in housing costs

In order to adapt housing cost to the available budget, many people look for a house quite far away from the place where they work. Something that in turn has a negative effect on the travel costs and the time involved. Others settle in a neighborhood where the quality of life is moderate to poor or rent a too expensive house. More than a million households spend much more than the maximum desirable percentage of income (40%) on housing, utilities, and transport.

Between 2012 and 2022, the average price of a home in the Netherlands rose from €233,000 to €380,000. In Amsterdam, the price doubled from €280,000 to €560,000. Living in the city is becoming a privilege of the wealthier part of the population.

It is often assumed that around 900,000 housing units will be needed in the Netherlands by 2030, of which 80% is intended for single-person households.

An approaching change?

It seems that there is a shift going on, at least in policy thinking. The aim is to build an average of 100,000 homes per year in the coming years and to shorten the lead time between planning and realization. Achieving these intentions is uncartain because construction is being seriously delayed by the nitrogen crisis. The slow pace of new construction has once again drawn attention to the possibility of using existing houses and buildings for a significant proportion of these new housing units. More so as it is estimated that 80% of demand comes from single-person households.

The existing housing stock offers large potential for the creation of new living spaces. This potential has been investigated by, among others, the Kooperative Architecten Werkplaats in Groningen, resulting in the report <em>Ruimte zat in de stad</em>. The research focuses on 1800 post-war neighbourhoods, built between 1950 and 1980 with 1.8 million homes, 720,000 of which are social rental homes. The conclusion is that the division and expansion of these homes can yield 221,000 new units in the coming years. Eligible for this are single-family houses, which can be divided into two, and porch apartment blocks, which can be divided into more units per floor. Dividing up existing ground-access homes and homes in apartment blocks is technically not difficult and the costs are manageable. This applies even more if the adjustments are carried out in combination with making the relevant homes climate neutral. In addition, huge savings are made on increasingly expensive materials.

Even more interesting is to combine compaction with topping. This means the addition of one or two extra floors, so that a lift can also be added to the existing apartments. In construction terms, such an operation can be carried out by using light materials and installing an extra foundation. A project group at Delft University of Technology has designed a prototype that can be used for all 847,000 post-war porch houses, all of which need major maintenance. This prototype also ensures that the buildings in which these homes are located become energy-neutral and include facilities for socializing and play. Hence the extra wide galleries, with stairs between the floors and common areas in the plinth (image below right).

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

14. Liveability

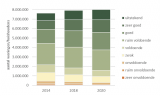

The picture shows the average development of the liveability per household in residential neighborhoods in the Netherlands from 2014 (source: Leefbaarheid in Nederland, 2020)

This is the 14th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. This post discusses how to improve the liveability of neighbourhoods. Liveability is defined as the extent to which the living environment meets the requirements and wishes set by residents.

Differences in liveability between Dutch neighbourhoods

From the image above can be concluded that more than half of all households live in neighborhoods to be qualified as at least 'good'. On the other hand, about 1 million households live in neighborhoods where liveability is weak or even less.

These differences are mainly caused by nuisance, insecurity, and lack of social cohesion. Locally, the quality of the houses stays behind.

The neighborhoods with a weak or poorer liveability are mainly located in the large cities. Besides the fact that many residents are unemployed and have financial problems, there is also a relatively high concentration of (mental) health problems, loneliness, abuse of alcohol and drugs and crime. However, many people with similar problems also live outside these neighbourhoods, spread across the entire city.

Integration through differentiation: limited success

The Netherlands look back on a 75 years period in which urban renewal was high on the agenda of the national and municipal government. Over the years, housing different income groups within each neighbourhood has played a major role in policy. To achieve this goal, part of the housing stock was demolished to be replaced by more expensive houses. This also happened if the structural condition of the houses involved gave no reason to demolishment.

Most studies show that the differentiation of the housing stock has rarely had a positive impact on social cohesion in a neighborhood and often even a negative one. The problems, on the other hand, were spread over a wider area.

Ensuring a liveable existence of the poor

Reinout Kleinhans justly states: <em>Poor neighborhoods are the location of deprivation, but by no means always the cause of it.</em> A twofold focus is therefore required: First and foremost, tackling poverty and a structural improvement of the quality of life of people in disadvantaged positions, and furthermore an integrated neighborhood-oriented approach in places where many disadvantaged people live together.

I have already listed measures to improve the quality of life of disadvantaged groups in an earlier post that dealt with social security. I will therefore focus here on the characteristics of an integrated neighbourhood-oriented approach.

• Strengthening of the remaining social cohesion in neighborhoods by supporting bottom-up initiatives that result in new connections and feed feelings of hope and recognition.

• Improvement of the quality of the housing stock and public space where necessary to stimulate mobility within the neighborhood, instead of attracting 'import' from outside.

• Allowing residents to continue living in their own neighborhood in the event of necessary improvements in the housing stock.

• Abstaining from large-scale demolition to make room for better-off residents from outside the neighborhood if there are sufficient candidates from within.

• In new neighborhoods, strive for social, cultural, and ethnic diversity at neighborhood level so that children and adults can meet each other. On 'block level', being 'among us' can contribute to feeling at home, liveability, and self-confidence.

• Curative approach to nuisance-causing residents and repressive approach to subversive crime through the prominent presence of community police officers who operate right into the capillaries of neighbourhoods, without inciting aggression.

• Offering small-scale assisted living programs to people for whom independent living is still too much of a task. This also applies to housing-first for the homeless.

• Strengthening the possibilities for identification and proudness of inhabitants by establishing top-quality play and park facilities, a multifunctional cultural center with a cross-district function and the choice of beautiful architecture.

• Improving the involvement of residents of neighbourhoods by trusting them and giving them actual say, laid down in neighborhood law.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

12. Water Management

This is the 12th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. This post deals with the question of how nature itself can help to deal with excessive rainfall and subsequently flooding of brooks and rivers, although these disasters are partially human-made.

Until now, flooding has mainly been combated with technical measures such as the construction of dykes and dams. There are many disadvantages associated with this approach and its effectiveness decreases. Nature-inclusive measures, on the other hand, are on the rise. The Netherlands is at the forefront of creating space for rivers to flood, where this is possible without too many problems.

Sponge areas

An important principle is to retain water before it ends up in rivers, canals, and sewers. The so-called sponge city approach can be incorporated into the fabric of new neighbourhoods and it creates sustainable, attractive places too. A combination of small and large parks, green roofs, wadis, but also private gardens will increase the water storage capacity and prevents the sewer system from becoming overloaded and flooding streets and houses. Steps are being taken in many places in the world; [China is leading the way](https://www\.dropbox\.com/s/47zxvl3kgbeeasa/Tale of two cities.pdf?dl=0) (photo top right). However, the intensity of the precipitation is increasing. In 2023, 75 cm of rain fell in Beijing in a few days. Under such conditions, local measures fall short. Instead, nature-inclusive measures must be applied throughout the river basin.

Retention basins

In new housing estates, water basins are constructed to collect a lot of water. Their stepped slopes make them pleasant places to stay in times of normal water level. The pictures on the left are from Freiburg (above) and Stockholm (below). The top center photo shows the construction of a retention basin in Lois Angeles.

Wadis

Wadis are artificial small-scale streams in a green bed with a high water-absorbing capacity. In the event of heavy rainfall, they collect, retain and discharge considerably more water than the sewer system (bottom center photo). Green strips, for example between sidewalks, cycle paths and roads also serve this purpose (photo bottom right: climate-adaptive streets in Arnhem).

Green roofs, roof gardens and soils

Green roofs look good, they absorb a lot of CO2 and retain water. The stone-covered urban environment is reducing the water-retaining capacity of the soil. Sufficiently large interspaces between paving stones, filled with crushed stone, ensure better permeability of streets and sidewalks. The same applies to half-open paving stones in parking lots.

Refrain from building in flood-prone areas

Up to the present day, flood-prone parts of cities are used for various purposes, often because the risk is underestimated or the pressure on space is very great. London's Housing and Climate Crises are on a Collision Course is the eloquent title of an article about the rapidly growing risk of flooding in London.

Hackney Wick is one of 32 growth centers set to help alleviate London's chronic housing shortage, which has already been repeatedly flooded by heavy rainfall. However, the construction of new homes continues. Measures to limit the flood damage at ground floor level include tiled walls and floors, water-inhibiting steel exterior doors, aluminum interior doors, kitchen appliances at chest height, closable sewers, and power supply at roof-level. Instead, floating neighbourhoods should be considered.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

AMS Conference 2024: Call for abstracts and special sessions

We invite you to contribute to the conference "Reinventing the City 2024 - Blueprints for messy cities?"

Deadline to submissions: November 14, 2023

Notification of acceptance: December 14, 2023

submit here>>

The AMS Scientific Conference (AMS Conference) explores and discusses how cities can transform themselves to become more livable, resilient and sustainable while offering economic stability. In the second edition of “Reinventing the City” (23-25 April 2024), the overarching theme will be <em>"</em>Blueprints for messy cities? Navigating the interplay of order and complexity'. In three captivating days, we will explore 'The good, the bad, and the ugly' (day 1), 'Amazing discoveries' (day 2) and 'We are the city' (day 3).

Call for abstracts

The AMS Conference seeks to engage scientists, policymakers, students, industry partners, and everyone working with and on cities from different backgrounds and areas of expertise. We therefore invite you to submit your scientific paper abstract, idea for a workshop or special session with us. Submissions should be dedicated to exploring the theme ‘Blueprints for messy cities?’. We especially invite young, urban rebels to raise their voice, as they are the inhabitants of our future cities.