Stay in the know on all smart updates of your favorite topics.

Civity wint Green Innovation Hub Contest 2023

Almere, 6 juli 2023 – Civity is de winnaar van de Green Innovation Hub Contest 2023, waar verschillende start- en scale-ups hun innovatieve oplossing voor een duurzame en inclusieve leefomgeving presenteerden. Dat bepaalde de jury (UPAlmere!, Amsterdam Smart City, BTG, Future City Foundation, Floor Almere, Windesheim, Aeres, Provincie Flevoland, PRICE, Horizon en VodafoneZiggo) gisteren tijdens de Green Innovation Hub Contest tijdens een stormachtige dag. Na een succesvolle pitch won de start-up uit Amersfoort de Golden Award voor hun innovatieve oplossing: een smartcity dataplatform voor de energietransitie. Hiermee verzekert Civity zich van begeleiding om haar concept verder te ontwikkelen, kantoorruimte en tickets voor de Smart City Congres 2023 in Barcelona.

De komende jaren worden er in de provincie Flevoland 130.000 nieuwe woningen gebouwd.. Nederlands grootste bouwopgave. Daarom hebben de gemeente Almere, de provincie Flevoland, VodafoneZiggo en haar partners de handen ineengeslagen met de organisatie van de Green Innovation Hub Contest 2023. Het doel van de wedstrijd is het vinden van innovatieve oplossingen die bijdragen aan een duurzame en inclusieve leefomgeving.

“We zitten in de grootste transitie van de afgelopen 50 jaar, waarin we zowel op ruimtelijk als op sociaal gebied uitdagingen hebben. Het is mooi dat de Green Innovation Hub Contest hier met nieuwe organisaties en nieuwe ideeën mee aan de slag gaat en dat Almere blijft geloven en investeren in groene innovatie.”, aldus hoofdjurylid Jan-Willem Wesselink, programmamanager bij Future City Foundation.

Contest Day

Start-ups en scale-ups konden zich tot 22 juni aanmelden. Uit alle inzendingen heeft de jury tien organisaties met de beste oplossingen geselecteerd. Zij hebben hun producten en diensten gisteren tijdens de Innovation Hub Contest Day gepresenteerd.

“De inspirerende oplossingen die zijn gepresenteerd, dragen allemaal bij aan de ontwikkeling van Almere als een duurzame en natuur-inclusieve stad.” vertelt jurylid Debby Kruit, Ecosystem Advisor UPALMERE! en Startup Mentor bij Startupbootcamp. “Ik kan niet wachten om te zien welke innovaties over een tijdje echt in Almere worden gerealiseerd.”

Golden Award

De oplossing van Civity werd tijdens de finale van de Green Innovation Hub Contest door de jury bekroond met de Golden Award. Dit betekent dat zij meegaan met de partners naar de Smart City Congres in Barcelona en dat zij coaching en ondersteuning ontvangen om hun product verder op te schalen in de markt.

Arjan Eeken, senior Architecture manager en innovatiestrateeg bij VodafoneZiggo: “De presentatie ging niet in op de technologische oplossing, maar op de toegevoegde waarde voor de maatschappij. De meest belangrijke discussie die er is: hoe deel je data voor de energieconsumptie.”

Directeur Roelof Schram van Civity is erg opgetogen: ”Hiermee zetten wij met ons bedrijf een fantastische volgende stap om onze smartcity dataplatform samen met experts verder op te schalen”.

Smart City tips for an innovative summer in Amsterdam

Whether you’re a visitor exploring Amsterdam, or a local opting for a staycation this summer, boredom is not on the agenda. There are some great things to do and see if you’re interested in innovation and sustainability. Delve into my curated list of smart city summer tips with exhibitions, activities and experiences from our partners and community. Zigzag across the city and discover the city from a different perspective!

1. Discover the city as a living place at the Landscape festival: ‘Met andere ogen’ (with other eyes)

Nature is a source of beauty and comfort, of relaxation and well-being, but it is now also in crisis. Diversity is declining and habitats are disappearing. In the ecological recovery lying ahead, the city plays a remarkable role: not only as a hotspot for biodiversity, but also as a meeting place where we can forge links between human and other life. Waag Futurelab invites you to set your sights on the Amsterdam Science Park and discover the city as a living place, together with artists, local residents and scientists. Take a walk along the walking route across the Amsterdam Science Park past all the installations and interventions.

From June until September 2023. Pick up a map at Café-Restaurant Polder (address: Science Park 201). Costs: free.

2. Take an architectural summer walk through new city areas

Arcam, the centre for architecture in Amsterdam, organises a series of architectural walks through neighbourhoods in development: Houthaven, Sloterdijk, Zuidas, Centrumeiland and Elzenhagen-Zuid. On Sundays from June to September, you can join a summer walk, led by an enthusiastic city expert, to visit and learn more about newly (to be) transformed areas of Amsterdam.

Every Sunday (from June to September) from different pick-up points. Costs: € 15,00 per person.

3. Fix your broken stuff at Repair Café Oud Noord

Give your broken belongings a second chance at the Repair Café in De Ceuvel (Metabolic Lab). Whether it's electronics, textiles, furniture, or bikes, the dedicated team at the Repair Café is there to assist with even the most challenging repairs. Join this community-driven initiative on the first Wednesday of each month! While the repairs are free, donations for used materials are warmly appreciated.

Every first Wednesday of the month (next up August 2, from 18:00-20:00) at De Ceuvel, Metabolic Lab. Costs: Free.

4. Green up your city with the NK Tegelwippen (‘National Tile Removal Championship’)

In the Netherlands, it's common to see apartment buildings, offices, and homes surrounded by tiles. This might be low-maintenance, but they're not particularly beautiful and do absolutely nothing to help the environment. We’re increasingly facing problems such as heat stress and flooding, and all those stone tiles in urbanised areas do not cool down on a hot day or let water through when it rains. Join the National Tile Removal Championship this summer! Remove tiles (for example in your garden) and replace them with plants and flowers for a greener city.

From March 21st till October 31st, more information via the website of NK Tegelwippen.

5. Learn more about our energy addition at the Energy Junkies exhibition

Our dependence on fossil fuels and the effects of our energy consumption on climate change are the focus of NEMO’s new exhibition for adults: Energy Junkies. NEMO invites you to explore the decisions that will determine our future. How would you transform our energy addiction into a healthy habit? Create your own carbon diet, choose the right medicines from the climate pharmacy and dream about a world where we are cured of our energy addiction. Visit Energy Junkies at NEMO’s Studio, the off-site location for adults on the Marineterrein in Amsterdam.

Energy Junkies is open from Wednesday – Sunday, from 12:00 – 17:30 until October 29. Costs: € 7,50

6. Visit the Maker Market

Meet passionate and innovative makers from all over the world at The Maker Market! Here you will find handmade products produced with love and craftsmanship. The event focuses on sustainable production processes and Fair Trade. Engage with the makers, hear their stories, and witness their creative processes. This way, you can discover products with a good story.

On Saturday July 28 (11:00-17:00), Sunday July 28 (12:00-17:00), Saturday August 26 (11:00-17:00) and Sunday August 27 (12:00-17:00) at the Passage. Costs: Free.

7. Book a tour at Mediametic

Get a glimpse behind the scenes at Mediametic! During their weekly tour on Friday, you’ll get the chance to peek inside their labs, in which they explore the possibilities of bio-materials for design, science and art. You’ll also visit the Clean lab, where Mediametic is currently focusing on the use of waste materials, as a source for new material. You get an introduction in the Aroma lab, their open perfume workshop and scent library where scent is explored as an artistic medium. And you will get to see the Plant lab, where herbs and edible flowers are grown for the restaurant in a sustainable way.

On Friday’s at 16:00, Mediametic. Costs: € 4,50 incl. a drink.

8. Keep your head cool! At Waag Open

It's getting hot in here! Since 1923, the KNMI (The Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute) measured 28 heat waves and almost half them occurred in the past 20 years. If this trend continues, the number of 'tropical' days (days above 30 degrees) will have doubled by 2050. But what are the consequences of these heat waves in people's homes? In countless Dutch (rental) homes, bedrooms heat up considerably in summer. And that can lead to physical and mental complaints: heat stress. During Waag Open: Keep your head cool, Lisanne Corpel (researcher at the Hogeschool van Amsterdam) shares her knowledge on measuring heat and the phenomenon of heat stress.

Thursday August 3 from 19:30-21:30 at Waag, Nieuwmarkt 4. Costs: € 7,50 incl. a drink.

As you explore these smart city summer tips in Amsterdam, let the innovative initiatives inspire you to make positive changes in your own life. Be sure to check out our platform for more exciting events and experiences. Do you have any other tips for inspiring smart city activities not to be missed this summer? Share them with the community in the comments!

Anders kijken en anders doen in de Metropool van Morgen

Dringende oproep van Femke Halsema tijdens zesde State of the Region.

Van grenzen aan de groei en zonnepanelen voor iedereen tot talenten werven op een nieuwe manier en een nieuw perspectief op nieuwkomers: als we brede welvaart echt een kans willen geven, moeten we anders kijken en anders doen. En daarvoor is vertrouwen cruciaal, zegt Femke Halsema in haar oproep. Welkom bij de 6e editie van State of the Region, in de Meervaart Amsterdam.

Duurzaamheid. Wonen. De energietransitie. Als presentatoren Tex de Wit en Janine Abbring via de Mentimeter het publiek vragen naar de grootste uitdaging voor de Metropool Amsterdam verschijnt er een gevarieerde woordwolk op het scherm. Armoedebestrijding wordt genoemd, minder vergaderen en bereikbaarheid.

Ook noemen veel mensen brede welvaart. “En dat is vandaag een belangrijk thema”, zegt Abbring. “In eerdere State of the Regions lag de focus meer op cijfers, op economische welvaart. Nu richten we ons ook op minder materiële zaken.”

Dat zien we terug in een paar filmpjes. Pallas Achterberg, Challenge Officer bij Alliander roept daarin op beter te luisteren, tot samenwerken op een andere manier, een samenwerking waarin we ons eigen belang ondergeschikt maken aan het gemeenschappelijke belang. We zien een kinderarts die zich afvraagt waarom we ons niet veel meer richten op preventie. We zien ondernemers die bij het werven van talent verder kijken dan alleen het cv en ondernemers die zonnepanelen betaalbaar maken voor iedereen.

Geen lege term

Het zijn de concrete voorbeelden die nauw aansluiten bij de jaarlijkse State of the Region, de speech van Femke Halsema tijdens het gelijknamige evenement. Ze is burgemeester van Amsterdam, maar vandaag vooral voorzitter van de Metropoolregio Amsterdam én van Amsterdam Economic Board. Die organiseren dit evenement samen met de gemeente Amsterdam, amsterdam&partners en ROM InWest.

Halsema herhaalt de oproep die vandaag centraal staat: anders kijken en anders doen. “We moeten fundamentele keuzes maken om ervoor te zorgen dat brede welvaart geen lege term wordt. Dat we het werkelijk gaan uitvoeren. Wij doen nu deze oproep. En ik hoop dat we die samen met inwoners, bedrijven, maatschappelijke instellingen en u in de zaal werkelijkheid kunnen laten worden.”

Bijzondere samenwerking

De Board-voorzitter is net terug uit Hatay, de Turkse provincie die zo zwaar werd getroffen door de aardbeving. Door slechte samenwerkingen lukt het de regio niet goed om de enorme schades te herstellen. Het leven ligt er stil. In Nederland zit die samenwerking in ons bloed. De eerste Nederlandse dijk liep langs het Gooi, via Diemen en Amsterdam naar het IJ en was het gevolg van een bijzondere samenwerking tussen boeren, vissers, de graaf en inwoners.

“Die samenwerking vraagt nog wel onze aandacht. Ons verdienmodel is aan vernieuwing toe. Economische groei zal hand in hand moeten gaan met sociaal-maatschappelijke vooruitgang. Onze huidige voorspoed bereikt nog lang niet iedereen. Inkomensverschillen zijn groot, er is te veel uitstoot van fijnstof, er zijn te weinig arbeidskrachten en er is een tekort aan woningen.”

De Metropool als meent

Toch ziet Halsema geen reden voor pessimisme. Met dank aan grote en kleine bedrijven die in de Metropool hun uitvalsbasis hebben verdienen we hier 20 procent van het bruto binnenlands product. De voorzieningen en kennisinstellingen zijn van hoog niveau. En we zijn een veerkrachtige regio.

Vertrouwen is volgens Halsema de kern van onze toekomstige samenwerking. “We kunnen niet met elkaar blijven concurreren, we moeten elkaar versterken. We moeten onze Metropool zien als de meent van vroeger, een gemeenschappelijke weidegrond waar we samen verantwoordelijk voor zijn. Als jij die niet goed gebruikt, heeft dat gevolgen voor de andere gebruikers. De Metropool is te lang beschouwd als onbeheerde, woeste grond waar geen samenwerking voor nodig is.”

Halsema haalt econoom en nobelprijswinnaar Elinor Ostrom aan, die pleitte voor goede instituties voor gemeenschappelijk beheer. “We beheren goederen die we moeten laten floreren voor het welvaren van de gehele gemeenschap, zegt zij. Dat betekent dat we altijd het belang van de ander hebben mee te wegen, ook dat van mensen in de rest van Nederland en de wereld en ook dat van toekomstige generaties.”

‘Een mega radicale transformatie’

Anders kijken en anders doen klinkt misschien eenvoudig, maar vraagt van iedereen in de Metropool Amsterdam een nieuwe manier van denken en doen. Op het podium gaat Femke Halsema hierover in gesprek met Ingo UytdenHaage, co-CEO van Adyen, architect Thomas Rau en onderzoeken en community builder Soraya Shawki. Wat vinden zij van de oproep anders te kijken en anders te doen?

Wat Thomas Rau, architect, ondernemer, innovator betreft gaat de oproep niet ver genoeg. “Het is nog niet radicaal genoeg. We hebben het over 2050, maar ik vind dat we een duidelijk beeld moeten hebben van waar we over zeven jaar als Metropool willen staan. Daarbij moeten we niet doen wat mogelijk is, maar wat nodig is: een mega radicale transformatie. En dat is niet altijd comfortabel.”

Expats

Ingo Uytdenhaage , co-CEO van Adyen is wat positiever. “Bedrijven kijken vaak al verder dan alleen maar naar geld verdienen. Wij kijken ook naar onze impact op de regio, op de stad.” Die impact van Adyen is bijvoorbeeld dat er veel expats voor hen werken, zegt Abbring, en die hebben ook allemaal woonruimte nodig. Uytdenhaage ziet dat anders. “Ik noem ze geen expats, het zijn jongeren van begin 30 die een lokaal contract hebben en dezelfde uitdagingen hebben als andere jonge Amsterdammers. En ze willen ook helemaal niet allemaal in de stad wonen.” Hij krijgt bijval van Halsema: “We hebben internationale arbeidskrachten nodig voor het werk dat er ligt. We kunnen de tekorten niet oplossen met eigen inwoners.”

Soraya Shawki, researcher/community bouwer Open Embassy die nieuwkomers wegwijs maakt in de Nederlandse samenleving. Zij had graag een concretere oproep gezien. “Er is bijvoorbeeld nog veel systemische ongelijkheid. Er zijn heel veel mensen hier die pas na vijf jaar mogen werken. Dat zijn allemaal mensen die in de zorg en techniek aan de slag kunnen gaan.” Onlangs sprak ze een Iraanse wiskundelerares die Nederlands en Engels spreekt. “De gemeente vond dat ze zo snel mogelijk aan de slag moest gaan en stuurde een vacature voor een kassamedewerker door. Er ligt hier ook een rol voor werkgevers, om trajecten voor nieuwkomers beschikbaar te maken.”

Lessen aan nieuwkomers

Adyen is daar bijvoorbeeld al mee bezig en geeft programmeerlessen aan nieuwkomers. Ook laat het bedrijf in speciale lessen op scholen zien hoe technologie werkt, om zo de interesse van jongeren voor techniek te wekken. Wat Halsema betreft is het een goed voorbeeld van hoe bedrijven in de afgelopen jaren een andere taakopvatting hebben gekregen. “Waar ze voorheen misschien doneerden aan culturele instellingen, zie je nu dat ze veel meer investeren in de lokale economie en met jongeren en inwoners praten.”

Volgens Shawki mag dat nog wel wat verder gaan, bij overheden én bedrijven. “Participatie is vaak nog een vinkje op een lijstje, het is niet ingebed waardoor er bij bedrijven en overheden weinig kennis is over wat er precies nodig is. En dat terwijl mensen letterlijk expert zijn over hun eigen ervaringen. Wij hebben bijvoorbeeld expertpools van mensen die ervaring hebben met de nieuwe Wet inburgering.”

Nieuwe ontmoetingen

Soraya Shawki en Ingo UytdenHaage kenden elkaar tot vandaag nog niet, terwijl er wel wat overlap zit in hun werkzaamheden. Anders kijken en anders doen gaat ook over dit soort ontmoetingen, stelt interviewer Abbring vast. “De toekomst ligt altijd in de mensen die je niet kent”, bevestigt Rau. “In gesprekken met mensen die je niet kent. Dus ga het gesprek aan. Wij zijn de oplossing.”

En Halsema besluit: “De Metropoolregio was te lang een soort noodzakelijk kwaad, maar volgens mij moeten we het omdraaien. Alle grote onderwerpen moeten we op regionaal niveau met elkaar bespreken. We moeten wantrouwen inruilen voor vertrouwen. Alleen zo kunnen we radicale stappen zetten.”

Wil je direct aan de slag? Op Anders kijken, anders doen vind je inspirerende interviews en mooie voorbeelden. Je kunt er je eigen initiatieven en manier van werken onder de loep nemen. Past die wel bij de Metropool van Morgen? Ook kun je je er inschrijven voor de werkateliers die we na de zomer gaan organiseren.

Voor het hoofdprogramma waren er twee side-events:

State of the Youth

De Young on Board is in gesprek gegaan over het betrekken van jongeren bij het vormgeven van de toekomst van de Metropoolregio Amsterdam. Het thema participatie bleek na dit weekend relevanter dan ooit. Hoe zorgen we voor brede maatschappelijke betrokkenheid en hoe zorgen we ervoor dat jongeren weer vertrouwen krijgen in de politiek èn hun stemrecht?

Paula Smith (docent-onderzoeker Social Work bij InHolland) gaf ons een stoomcursus over jongerenparticipatie. Ze ging daarbij niet alleen in op de verschillen tussen jongeren en de rest van het electoraat, maar ook over de verschillen tussen jongeren. De belangrijkste boodschap van Paula is dat we jongerenparticipatie moeten gaan verankeren in (beleid)structuren. Als je jongeren nu betrekt creëer je namelijk geëngageerde burgers voor later.

Vervolgens zijn we met Younes Douari (Represent Jezelf) en Kimberley Snijders (voorzitter van De Nationale Jeugdraad) en Paula Smith in gesprek gegaan. Zij deelden hun ervaringen over wat er in de praktijk werkt om jongeren te betrekken in het maatschappelijke debat en bij het vormgeven van beleid. We hebben daarbij een aantal belangrijke lessen opgehaald, namelijk:

Betrek jongeren op tijd, en gebruik ze niet als windowdressing.

Maak gebruik van sociale structuren in wijken en dorpen en ga naar jongeren toe

Durf het aan om het resultaat echt uit handen te geven

Economische Verkenningen

Het andere side event was volledig gewijd aan de Economische Verkenningen MRA 2023.

Transition Day 2023: Mobility Justice - Power structures and engaging your target group

While our mobility system and its options are continuously expanding, there’s a growing number of people who feel excluded from the mobility system and experience a lack of access to services like public transport and shared mobility options. The concept of Mobility Poverty shows there are a variety of reasons for this exclusion, ranging from economic and geographical reasons, to falling behind on digital skills. If we want to move towards ‘Mobility Justice’, we would need a detailed image of the groups experiencing this exclusion and we would need a variety of actors to come up with -and implement- creative solutions to this emerging problem.

For the past months, Chris de Veer and I have been busy setting up a regional coalition and program on this subject. Because it’s becoming clear we’re discussing a problem we, a pool of mobility specialists, are not experiencing ourselves, we decided to critically look at what parties have a seat at the table. During the Amsterdam Smart City Transition Day on June 6th, we gathered input and reflections on the power structures in play and considerations when involving your target group in decision making.

Understanding power relations and structures when working on transitions

When designing solutions and innovative policies, it’s important to understand and be aware of the power structures in play. Our partner Kennisland is concerned with the topic and introduced this discussion within our network during on of our ‘Kennissessies’ earlier this year. Together with this session’s participants, we used their method to evaluate which parties have been involved in the initial phase of our Mobility Justice challenge.

It became clear that it had been mostly governmental parties which were involved in exploring the topic and initiating the design of a cooperation program. While this is of importance for practical matters like funding and political support, the group should have been diversified when we started exploring the problem and its solutions. The (target) group we’re talking about is currently lacking the power to help design both the collaboration process itself and the initiatives that should help fight Mobility Poverty.

Considerations when engaging with your target group

There was a general consensus in the group that we should now make more of an effort to engage with our target group. But how exactly? The group discussed different existing forms of involving a target group in decision making and advised us on matters to consider, namely;

- Decide in what stage(s) of the process collaboration or input is needed. Exploring the problem will require a completely different conversation and method compared to the stage of co-designing solutions.

- Be very clear about what you’ll use the outcomes for. If you decide to gather input from - and collaborate with your target group, you’ll need to actually incorporate the outcomes within your process. This is necessary to maintain the groups trust and validate their efforts.

- Besides defining problems and exploring its solutions, evaluation of the initiatives that follow will be equally important. Special efforts need to be put into place to keep the dialogue going with the target group during and after testing initiatives.

Next steps: Harnessing the power of community centres

When discussing potential next steps for the group, one of the session’s participants reminded us of the power of community centres. She mentioned an example in her own neighbourhood, where a group of neighbours initiated a sharing vehicle for elderly/disabled people. This example illustrated how local communities know best what specific problems or needs are at play, and how to set up solutions in a quick manner.

This conversation inspired us to now look for relevant local initiatives and community centres in the Amsterdam region. With their help, we hope to better understand problems related to Mobility Poverty and what specific solutions people need within their local context.

A call to the community

I’m now wondering if there is anyone in our Amsterdam Smart City community who could link us to local initiatives and community centres in the Amsterdam region? Mobility-related topics are a plus, but this is certainly not necessarily. Any advice or tips to share? Send me an email at pelle@amsterdamsmartcity.com. This summer, we’ll design the continuation of this project.

Nature Assessments Solution: Introducing Link by Metabolic Software

This week, Metabolic launched its first SaaS solution: Link, by Metabolic Software!

After 10 years of helping organizations understand their impact on nature, Metabolic has created a way to automate this process to help more people faster.

Link enables companies to understand their impact and identify nature-related risks across their supply chain. It helps them mitigate negative effects, protect biodiversity, and find opportunities for sustainable initiatives

#natureassessment #LinkbyMetabolic

New research: 6 strategies for building homes in the Netherlands within planetary boundaries

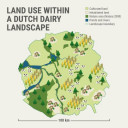

The Netherlands has a housing problem: Too many people, and not enough homes. The country plans to build 100,000 new homes each year through 2030.

But can the country build this much without exceeding our planetary boundaries?

In partnership with Copper8, NIBE, and Alba Concepts, Metabolic has proposed six strategies. When combined, these could reduce total CO2 emissions from construction by up to 33% and the use of raw materials by 40%.

Do you want to learn more? Find all the details in their newest research, which was presented last week in Amsterdam!

Demoday #19: CommuniCity worksession

Without a doubt, our lives are becoming increasingly dependent on new technologies. However, we are also becoming increasingly aware that not everyone benefits equally from the opportunities and possibilities of digitization. Technology is often developed for the masses, leaving more vulnerable groups behind. Through the European-funded CommuniCity project, the municipality of Amsterdam aims to support the development of digital solutions for all by connecting tech organisations to the needs of vulnerable communities. The project will develop a citizen-centred co-creation and co-learning process supporting the cities of Amsterdam, Helsinki, and Porto in launching 100 tech pilots addressing the needs of their communities.

Besides the open call for tech-for-good pilots, the municipality of Amsterdam is also looking for a more structural process for matching the needs of citizens to solutions of tech providers. During this work session, Neeltje Pavicic (municipality of Amsterdam) invited the Amsterdam Smart City network to explore current bottlenecks and potential solutions and next steps.

Process & questions

Neeltje introduced the project using two examples of technology developed specifically for marginalised communities: the Be My Eyes app connects people needing sighted support with volunteers giving virtual assistance through a live video call, and the FLOo Robot supports parents with mild intellectual disabilities by stimulating the interaction between parents and the child.

The diversity of the Amsterdam Smart City network was reflected in the CommuniCity worksession, with participants from governments, businesses and knowledge institutions. Neeltje was curious to the perspectives of the public and private sector, which is why the group was separated based on this criteria. First, the participants identified the bottlenecks: what problems do we face when developing tech solutions for and with marginalised communities? After that, we looked at the potential solutions and the next steps.

Bottlenecks for developing tech for vulnerable communities

The group with companies agreed that technology itself can do a lot, but that it is often difficult to know what is already developed in terms of tech-for-good. Going from a pilot or concept to a concrete realization is often difficult due to the stakeholder landscape and siloed institutions. One of the main bottlenecks is that there is no clear incentive for commercial parties to focus on vulnerable groups. Another bottleneck is that we need to focus on awareness; technology often targets the masses and not marginalized groups who need to be better involved in the design of solutions.

In the group with public organisations, participants discussed that the needs of marginalised communities should be very clear. We should stay away from formulating these needs for people. Therefore, it’s important that civic society organisations identify issues and needs with the target groups, and collaborate with tech-parties that can deliver solutions. Another bottleneck is that there is not enough capital from public partners. There are already many pilots, but scaling up is often difficult.. Therefore solutions should have a business, or a value-case.

Potential next steps

What could be the next steps? The participants indicated that there are already a lot of tech-driven projects and initiatives developed to support vulnerable groups. A key challenge is that these initiatives are fragmented and remain small-scale because there is insufficient sharing and learning between them. A better overview of what is already happening is needed to avoid re-inviting the wheel. There are already several platforms to share these types of initiatives but they do not seem to meet the needs in terms of making visible tested solutions with most potential for upscaling. Participants also suggested hosting knowledge sessions to present examples and lessons-learned from tech-for-good solutions, and train developers to make technology accessible from the start. Legislation can also play a role: by law, technology must meet accessibility requirements and such laws can be extended to protect vulnerable groups. Participants agreed that public authorities and commercial parties should engage in more conversation about this topic.

In response to the worksession, Neeltje mentioned that she gained interesting insights from different angles. She was happy that so many participants showed interest in this topic and decided to join the session. In the coming weeks, Neeltje will organise a few follow-up sessions with different stakeholders. Do you have any input for her? You can contact me via sophie@amsterdamsmartcity.com, and I'll connect you to Neeltje.

Opening Green Innovation Hub: startschot voor digitale innovatie in Almere

Op woensdag 22 februari heeft de Green Innovation Hub in Almere officieel zijn deuren geopend. De publiek-private samenwerking tussen de Gemeente Almere, Provincie Flevoland en telecombedrijf VodafoneZiggo richt zich op de ontwikkeling van digitale innovaties op het gebied van bouw, voedsel, energie, mobiliteit en (digitale) inclusie.

Almere bouwt de komende vijftien jaar 130.000 nieuwe woningen. Daarnaast wil de gemeente in 2030 klimaatneutraal zijn. Hiervoor is integrale, duurzame en inclusieve gebiedsontwikkeling belangrijk.

Broedplaats

De Green Innovation Hub is een broedplaats voor ontmoeting, samenwerking en innovatie. Partijen ontwikkelen digitale oplossingen voor een gezonde stadsomgeving, lokale voedselzekerheid, mobiliteit, circulair bouwen, energiedistributie en sociale verbondenheid tussen stadsbewoners. Gezamenlijke innovaties worden getest en opgeschaald op speciale ‘greenfield' locaties.

Open ecosysteem

De Green Innovation Hub is een broedplaats voor ontmoeting, samenwerking en innovatie. Partijen ontwikkelen digitale oplossingen voor een gezonde stadsomgeving, lokale voedselzekerheid, mobiliteit, circulair bouwen, energiedistributie en sociale verbondenheid tussen stadsbewoners. Gezamenlijke innovaties worden getest en opgeschaald op speciale ‘greenfield’ locaties. De Green Innovation Hub is een open ecosysteem, waarin partners, het bedrijfsleven, overheden en het onderwijs.

Innovatiekracht

Wethouder Maaike Veeningen: “Met deze samenwerking willen we de innovatiekracht van Almere vergroten. Digitalisering en technologie zijn daarbij onmisbaar, net als de kennis en kwaliteiten van inwoners van onze regio. Met de Green Innovation Hub in het hart van de stad laten we zien hoe belangrijk duurzame en inclusieve gebiedsontwikkeling voor ons is.”

Gedeputeerde Jan Nico Appelman: “Provincie Flevoland ondersteunt van harte de Green Innovation Hub: een plek waar samenwerken, innoveren en ontmoeten centraal staat. Digitalisering én duurzaamheid zijn twee thema’s die belangrijk zijn voor de ontwikkeling onze provincie. Hiermee past de Hub ook uitstekend in de groeiambitie van Almere."

Vragen van morgen

Laura van Gestel, directeur duurzaamheid van VodafoneZiggo: “Als telecombedrijf willen we onze impact op het milieu hebben gehalveerd in 2025. Tegelijk willen we twee miljoen mensen vooruithelpen in de samenleving. Hoe gaan we in de toekomst wonen en werken? Welke rol kunnen we daarin spelen? Belangrijke vragen die grote thema’s raken als zorg en mobiliteit, maar ook klimaatverandering en sociale ongelijkheid. Met de Green Innovation Hub willen we samen oplossingen ontwikkelen voor de vragen van morgen.”

How Berlin & Amsterdam are Designing the City from the Bottom-Up

City governments can have grand ideas and dreams about changing a city and revolutionizing services, but without a clear design and focus on building a base, many ideas and innovations can fall through. Amsterdam Smart City’s Programme Director, Leonie van den Beuken, was invited to speak about how to design a city from the bottom-up at the Smart City Expo World Congress in Barcelona.

Ralf Kleindiek, Chief Digital Officer and State Secretary for Digital Affairs and Administrative Modernization for the City of Berlin, and Caroline Paulick-Thiel, Executive Director for Politics of Tomorrow and the Co-Founder of nextlearning, joined her in this discussion.

Leonie highlighted that it is crucial to include residents in decision-making processes, but at the same time, we need to address how difficult the process and outcome may be. For example, if we want streets with less cars, residents need to give up their cars and find other alternatives. Key to designing the city from the bottom-up is to ask the right questions in an understandable and tangible way.

Watch the full interview and other interesting talks via the website Tomorrow. City: https://tomorrow.city/a/berlin-and-amsterdam-or-designing-the-city-from-the-bottom-up

Wat mensen beweegt: ‘We hebben meer luisterambtenaren nodig’

Duurzaam reisgedrag kun je niet stimuleren zonder écht te luisteren naar de afwegingen die mensen maken bij hun keuze voor een vervoermiddel. En daar schort het nu nog regelmatig aan, stelt gedragswetenschapper Reint Jan Renes.

-> Lees dit artikel op NEMO Kennislink

Dit artikel is onderdeel van het project ''Wat mensen beweegt'. Waarin NEMO Kennislink, in samenwerking met lectoraat Creative Media for Social Change van de Hogeschool voor Amsterdam, het reisgedrag in het ArenA-gebied onderzoekt. NEMO Kennislink bevroeg hiervoor een aantal reguliere bezoekers.

- Concertganger Josina (58) reist al haar hele leven met het openbaar vervoer

- Activiste Jeanette Chedda (38) over inclusie voor duurzame mobiliteit

- Ondernemer en voetbalfanaat Gerco laat zijn auto niet staan

- Student Sander (24) komt (bijna) overal met ov en fiets

Slotbijeenkomst 'Wat mensen beweegt' in NEMO op 8 september om 14.30

In samenwerking met VU-onderzoeker en theatermaker Frank Kupper én theatermaker Bartelijn Ouweltjes gaan we de verhalen van bezoekers met u delen, door middel van improvisatietheater. Improvisatietheater is een mooie manier om emoties, dilemma’s en persoonlijke waarden uit te lichten, goed te beluisteren en misschien nog eens te hernemen. Zo leren we de bezoekers goed kennen – wat weer te vertalen is naar beleid en communicatie. -> Lees meer

Partners

In dit project werken we nauw samen met Johan Cruijff Arena, AFAS Live, Ziggo Dome , Platform Smart Mobility Amsterdam, ZO Bereikbaar, het Amsterdam Smart City netwerk, CTO Gemeente Amsterdam.

De paling als Amsterdammer

Darko Lagunas is milieusocioloog, en etnografisch onderzoeker. In zijn werk probeert hij juist onderdrukte stemmen die we niet horen een podium te geven. Dat doet hij met geschreven tekst, fotografie en korte films. Hij luistert naar mensen, maar ook naar wat hij noemt, meer-dan-mensen; dieren, planten, zee, en meer. Op dit moment doet hij onderzoek naar de paling als Amsterdammer bij de Ambassade van de Noordzee.

‘Door te luisteren naar meer dan alleen de mens, zien we de grotere structurele problemen waar mensen en meer-dan-mensen slachtoffer van zijn.’

* Elke maand interviewt De Gezonde Stad een duurzame koploper. Deze keer spreken we Darko Lagunas. We gingen bij hem langs terwijl hij onderzoek deed naar de stem voor de paling! Lees het hele interview op onze website.

SoTecIn Factory

SoTecIn Factory is launched!

Committed to improving the resilience and sustainability of European industry, SoTecIn Factory will support the transformation of industrial value chains to become low-carbon and circular.

Our goal? Build 30 mission-driven ventures distributed in 20+ European countries!

Make sure to follow their journey through SoTecIn Factory and find out more about the projects here: https://sotecinfactory.eu/

Science-Based Targets Network

How can a modern multinational company transition its value chain to preserve nature and biodiversity rather than deplete it?

Metabolic, WWF-France and the Science-Based Targets Network have worked with Bel to understand what areas to target and where the most positive impacts on biodiversity could be made.

Bel will share their best practices, helping other companies to see which methods work overtime. Together with SBTN, we invite more companies to join the effort.

23. Epilogue: Beyond the 'Smart City'

In the last episode of the Better cities: The contribution of digital technology-series, I will answer the question that is implied in the title of the series, namely how do we ensure that technology contributes to socially and environmentally sustainable cities. But first a quick update.

Smart city, what was it like again?

In 2009, IMB launched a global marketing campaign around the previously little-known concept of 'smart city' with the aim of making city governments receptive to ICT applications in the public sector. The initial emphasis was on process control (see episode 3). Especially emerging countries were interested. Many made plans to build smart cities 'from scratch', also meant to attract foreign investors. The Korean city of Songdo, developed by Cisco and Gale International, is a well-known example. The construction of smart cities has also started in Africa, such as Eko-Atlantic City (Nigeria), Konzo Technology City and Appolonia City (Ghana). So far, these cities have not been a great success.

The emphasis soon shifted from process control to using data from the residents themselves. Google wanted to supplement its already rich collection of data with data that city dwellers provided with their mobile phones to create a range of new commercial applications. Its sister company Sidewalk Labs, which was set up for that purpose, started developing a pilot project in Toronto. That failed, partly due to the growing resistance to the violation of privacy. This opposition has had global repercussions and led in many countries to legislation to better protect privacy. China and cities in Southeast Asia - where Singapore is leading the way - ignored this criticism.

The rapid development of digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence, gave further impetus to discussion about the ethical implications of technology (episodes 9-13). Especially in the US, applications in facial recognition and predictive police were heavily criticized (episode 16). Artificial intelligence had meanwhile become widespread, for example to automate decision-making (think of the infamous Dutch allowance affair) or to simulate urban processes with, for example, digital twins (episode 5).

This current situation - particularly in the Netherlands - can be characterized on the one hand by the development of regulations to safeguard ethical principles (episode 14) and on the other by the search for responsible applications of digital technology (episode 15). The use of the term 'smart city' seems to be subject to some erosion. Here we are picking up the thread.

Human-centric?

The dozens of descriptions of the term 'smart city' not only vary widely but they also evoke conflicting feelings. Some see (digital) technology as an effective means of urban growth; others see it as a threat. The question is therefore how useful the term 'smart city' is still. Touria Meliani, alderman of Amsterdam, prefers to speak of 'wise city' than of 'smart city' to emphasize that she is serious about putting people first. According to her, the term 'smart city' mainly emphasizes the technical approach to things. She is not the first. Previously, Daniel Latorre, place making specialist in New York and Francesco Schianchi, professor of urban design in Milan also argued for replacing 'smart' with 'wise'. Both use this term to express that urban policy should be based profoundly on the wishes and needs of citizens.

Whatever term you use, it is primarily about answering the question of how you ensure that people - residents and other stakeholders of a city - are put in the center. You can think of three criteria here:

1. An eye for the impact on the poorest part of the population

There is a striking shift in the literature on smart cities. Until recently, most articles focused on the significance of 'urban tech' for mobility, reduction of energy use and public safety. In a short time, much more attention has been paid to subjects such as the accessibility of the Internet, the (digital) accessibility of urban services and health care, energy and transport poverty and the consequences of gentrification. In other words, a shift took place from efficiency to equality and from physical interventions to social change. The reason is that many measures that are intended to improve the living environment led to an increase in the (rental) price and thus reduce the availability of homes.

2. Substantial share of co-creation

Boyd Cohen distinguishes three types of smart city projects. The first type (smart city 1.0) is technology- or corporate-driven. In this case, companies deliver instruments or software 'off the shelf'. For example, the provision of a residential area with adaptive street lighting. The second type (smart city 2.0) is technology enabled, also known as government-driven. In this case, a municipality develops a plan and then issues a tender. For example, connecting and programming traffic light installations, so that emergency services and public transport always receive the green light. The third type (smart city 3.0) is community-driven and based on citizen co-creation, for example an energy cooperative. In the latter case, there is the greatest chance that the wishes of the citizens concerned will come first.

A good example of co-creation between different stakeholders is the development of the Brain port Smart District in Helmond, a mixed neighborhood where living, working, generating energy, producing food, and regulating a circular neighborhood will go hand in hand. The future residents and entrepreneurs, together with experts, are investigating which state-of-the-art technology can help them with this.

3. Diversity

Bias among developers plays a major role in the use of artificial intelligence. The best way to combat bias (and for a variety of other reasons, too) is to use diversity as a criterion when building development teams. But also (ethical) committees that monitor the responsible purchasing and use of (digital) technologies are better equipped for their task the more diverse they are.

Respecting urban complexity

In his essay The porous city, Gavin Starks describes how smart cities, with their technical utopianism and marketing jargon, ignore the plurality of the drivers of human behavior and instead see people primarily as homo economicus, driven by material gain and self-interest.

The best example is Singapore – the number 1 on the Smart City list, where techno-utopianism reigns supreme. This one-party state provides prosperity, convenience, and luxury using the most diverse digital aids to everyone who exhibits desirable behavior. There is little room for a differing opinion. A rapidly growing number of CCTV cameras – soon to be 200,000 – ensures that everyone literally stays within the lines. If not, the culprit can be quickly located with automatic facial recognition and crowd analytics.

Anyone who wants to understand human life in the city and does not want to start from simplistic assumptions such as homo economicus must respect the complexity of the city, try to understand it, and know that careless intervention might have huge unintended consequences.

The complexity of the city is the main argument against the use of reductionist adjectives such as 'smart', but also 'sharing', circular, climate-neutral', ‘resilient' and more. In addition, the term smart refers to a means that is rarely seen as an aim as such. If an adjective were desirable, I prefer the term 'humane city'.

But whatever you name a city, it is necessary to emphasize that it is a complex organism with many facets, the coherence of which must be well understood by all stakeholders for the city to prosper and its inhabitants to be happy.

Digitization. Two tracks

City authorities that are aware of the complexity of their city can best approach digitization along two tracks. The first aims to translate the city's problems and ambitions into policy and consider digital instruments a part of the whole array of other instruments. The second track is the application of ethical principles in the search for and development of digital tools. Both tracks influence each other.

Track 1: The contribution of digital technology

Digital technology is no more or less than one of the instruments with which a city works towards an ecologically and socially sustainable future. To articulate what such a future is meaning, I introduced Kate Raworth's ideas about the donut economy (episode 9). Designing a vision for the future must be a broadly supported democratic process. In this process, citizens also check the solution of their own problems against the prosperity of future generations and of people elsewhere in the world. Furthermore, policy makers must seamlessly integrate digital and other policy instruments, such as legislation, funding, and information provision (episode 8).

The most important question when it comes to (digital) technology is therefore which (digital) technological tools contribute to the realization of a socially and ecologically sustainable city.

Track 2: The ethical use of technology

In the world in which we realize the sustainable city of the future, digital technology is developing rapidly. Cities are confronted with these technologies through powerful smart city technology marketing. The most important question that cities should ask themselves in this regard is How do we evaluate the technology offered and that we want to develop from an ethical perspective. The first to be confronted with this question—besides hopefully the industry itself—is the department of the Chief Information or Technology officer. He or she naturally participates in the first track-process and can advise policymakers at an early stage. I previously inventoried (ethical) criteria that play a role in the assessment of technological instrument.

In the management of cities, both tracks come together, resulting in one central question: Which (digital) technologies are eligible to support us towards a sustainable future in a responsible way. This series has not provided a ready-made answer; this depends on the policy content and context. However, the successive editions of this series will have provided necessary constituents of the answer.

In my e-book Cities of the Future. Always humane, smart if helpful, I have carried out the policy process as described above, based on current knowledge about urban policy and urban developments. This has led to the identification of 13 themes and 75 actions, with references to potentially useful technology. You can download the e-book here:

Abuse of artificial intelligence by the police in the US. More than bias

The 16th episode of the series Building sustainable cities - The contribution of digital technology reveals what can happen if the power of artificial intelligence is not used in a responsible manner.

The fight against crime in the United States, has been the scene of artificial intelligence’s abuse for years. As will become apparent, this is not only the result of bias. In episode 11, I discussed why artificial intelligence is a fundamentally new way of using computers. Until then, computers were programmed to perform operations such as structuring data and making decisions. In the case of artificial intelligence, they are trained to do so. However, it is still people who design the instructions (algorithms) and are responsible for the outcomes, although the way in which the computer performs its calculations is increasingly becoming a 'black box'.

Applications of artificial intelligence in the police

Experienced detectives are traditionally trained to compare the 'modus operandi' of crimes to track down perpetrators. Due to the labor-intensive nature of the manual implementation, the question soon arose as to whether computers could be of assistance. A first attempt to do so in 2012 in collaboration with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology resulted in grouping past crimes into clusters that were likely to have been committed by the same perpetrator(s). When creating the algorithm, the intuition of experienced police officers was the starting point. Sometimes it was possible to predict where and when a burglar might strike, leading to additional surveillance and an arrest.

These first attempts were soon refined and taken up by commercial companies. The two most used techniques that resulted are predictive policing (PredPol) and facial recognition.

In the case of predictive policing, patrols are given directions in which neighborhood or even street they should patrol at a given moment because it has been calculated that the risk of crimes (vandalism, burglary, violence) is then greatest. Anyone who behaves 'suspiciously' risks to be arrested. Facial recognition plays also an important role in this.

Both predictive policing and facial recognition are based on a "learning set" of tens of thousands of "suspicious" individuals. At one point, New York police had a database of 48,000 individuals. 66% of those were black, 31.7% were Latino and only 1% were white. This composition has everything to do with the working method of the police. Although drug use in cities in the US is common in all neighborhoods, policing based on PredPol and similar systems is focused on a few neighborhoods (of color). Then, it is not surprising that most drug-related crimes are retrieved there and, as a result, the composition of the database became even more skewed.

Overcoming bias

In these cases, 'bias' is the cause of the unethical effect of the application of artificial intelligence. Algorithms always reflect the assumptions, views, and values of their creators. They do not predict the future, but make sure that the past is reproduced. This also applies to applications outside the police force. The St. George Hospital Medical School in London has employed disproportionately many white males for at least a decade because the leather set reflected the incumbent staff. The criticized Dutch System Risk Indication System also uses historical data about fines, debts, benefits, education, and integration to search more effectively for people who abuse benefits or allowances. This is not objectionable but should never lead to 'automatic' incrimination without further investigation and the exclusion of less obvious persons.

The simple fact that the police have a disproportionate presence in alleged hotspots and are very keen on any form of suspicious behavior means that the number of confrontations with violent results has increased rapidly. In 2017 alone, police crackdowns in the US resulted in an unprecedented 1,100 casualties, of which only a limited number of whites. In addition, the police have been engaged in racial profiling for decades. Between 2004-2012, the New York Police Department checked more than 4.4 million residents. Most of these checks resulted in no further action. In about 83% of the cases, the person was black or Latino, although the two groups together make up just over half of the population. For many citizens of colour in the US, the police do not represent 'the good', but have become part of a hostile state power.

In New York, in 2017, a municipal provision to regulate the use of artificial intelligence was proposed, the Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology Act (POST). The Legal Defense and Educational Fund, a prominent US civil rights organization, urged the New York City Council to ban the use of data made available because of discriminatory or biased enforcement policies. This wish was granted in June 2019, and this resulted in the number of persons included in the database being reduced from 42,000 to 18,000. It concerned all persons who had been included in the system without concrete suspicion.

San Francisco, Portland, and a range of other cities have gone a few steps further and banned the use of facial recognition technology by police and other public authorities. Experts recognize that the artificial intelligence underlying facial recognition systems is still imprecise, especially when it comes to identifying the non-white population.

The societal roots of crime

Knowledge of how to reduce bias in algorithms has grown, but instead of solving the problem, awareness has grown into a much deeper problem. It is about the causes of crime itself and the realization that the police can never remove them.

Crime and recidivism are associated with inequality, poverty, poor housing, unemployment, use of alcohol and drugs, and untreated mental illness. These are also dominant characteristics of neighborhoods with a lot of crime. As a result, residents of these neighborhoods are unable to lead a decent life. These conditions are stressors that influence the quality of the parent-child relationship too: attachment problems, insufficient parental supervision, including tolerance of alcohol and drugs, lack of discipline or an excess of authoritarian behavior. All in all, these conditions increase the likelihood that young people will be involved in crime, and they diminish the prospect of a successful career in school and elsewhere.

The ultimate measures to reduce crime in the longer term and to improve security are: sufficient income, adequate housing, affordable childcare, especially for 'broken families' and unwed mothers and ample opportunities for girls' education. But also, care for young people who have encountered crime for the first time, to prevent them from making the mistake again.

Beyond bias

This will not solve the problems in the short term. A large proportion of those arrested by the police in the US are addicted to drugs or alcohol, are severely mentally disturbed, have serious problems in their home environment - if any - and have given up hope for a better future. Based on this understanding, the police in Johnson County, Kansas, have been calling for help from mental health professionals for years, rather than handcuffing those arrested right away. This approach has proved successful and caught the attention of the White House during the Obama administration. Lynn Overmann, who works as a senior advisor in the president’s technology office, has therefore started the Data-Driven Justice Initiative. The immediate reason was that the prisons appeared to be crowded by seriously disturbed psychiatric patients. Coincidentally, Johnson County had an integrated data system that stores both crime and health data. In other cities, these are kept in incomparable data silos. Together with the University of Chicago Data Science for Social Good Program, artificial intelligence was used to analyze a database of 127,000 people. The aim was to find out, based on historical data, which of those involved was most likely to be arrested within a month. This is not with the intention of hastening an arrest with predictive techniques, but instead to offer them targeted medical assistance. This program was picked up in several cities and in Miami it resulted in a 40% reduction in arrests and the closing of an entire prison.

What does this example teach? The rise of artificial intelligence caused Wire editor Chris Anderson to call it the end of the theory. He couldn't be more wrong! Theory has never disappeared; at most it has disappeared from the consciousness of those who work with artificial intelligence. In his book The end of policing, Alex Vitale concludes: Unless cities alter the police's core functions and values, use by police of even the most fair and accurate algorithms is likely to enhance discriminatory and unjust outcomes (p. 28). Ben Green adds: The assumption is: we predicted crime here and you send in police. But what if you used data and sent in resources? (The smart enough city, p. 78).

The point is to replace the dominant paradigm of identifying, prosecuting and incarcerating criminals with the paradigm of finding potential offenders in a timely manner and giving them the help, they need. It turns out that it's even cheaper. The need for the use of artificial intelligence is not diminishing, but the training of the computers, including the composition of the training sets, must change significantly. It is therefore recommended that diverse and independent teams design such a training program based on a scientifically based view of the underlying problem and not leaving it to the police itself.

This article is a condensed version of an earlier article The Safe City (September 2019), which you can read by following the link below, supplemented with data from Chapter 4 Machine learning's social and political foundationsfrom Ben Green's book The smart enough city (2020).

This week: Start of the third part of the Better cities-series.

In the first part of the series, I explained why digital technology 'for the good' is a challenge. The second part dealt with ethical criteria behind its responsible use. In the third part I have selected important field that will benefit from the responsible application of digital technology:

16 Abuse of artificial intelligence by the police in the US. More than bias

17 How can digital tools help residents to regain ownership of the city?

18 Will MaaS reduce the use of cars?

19 Digital tools as enablers towards a circular economy

20 Smart grids: where social and digital innovation meet

21 Risks and opportunities of digitization in healthcare

22 Two 100-city missions: Ill-considered leaps forward

23 Epilogue: Beyond the smart city

The link below enables you to open all previous episodes, also in Dutch language.

12. Ethical principles and applications of digital technology: Internet of things, robotics, and biometrics

In the 12th and 13th episode of the series Better cities: The contribution of digital technology, I will use the ethical principles from the 9th episode to assess several applications of digital technology. This episode discusses: (1) Internet of Things, (2) robotics and (3) biometrics. Next week I will continue with (4) Immersive technology (augmented and virtual reality), (5) blockchain and (6) platforms.

These techniques establish reciprocal connections (cybernetic loops) between the physical and the digital world. I will describe each of them briefly, followed by comments on their ethical aspects: privacy, autonomy, security, control, human dignity, justice, and power relations, insofar relevant. The book Opwaarderen: Borgen van publieke waarden in de digitale samenleving. Rathenau Instituut 2017 proved to be valuable for this purpose. Rathenau Institute 2017.

1. Internet-of-Things

The Internet-of-Things connects objects via sensors with devices that process this data (remotely). The pedometer on the smartphone is an example of data collection on people. In time, data about everyone's health might be collected and evaluated at distance. For the time being, this mainly concerns data of objects. A well-known example is the 'smart meter'. More and more household equipment is connected to the Internet and transmits data about their use. For a long time, Samsung smart televisions had a built-in television camera and microphone with which the behavior of the viewers could be observed. Digital roommates such as Alexa and Siri are also technically able to pass on everything that is said in their environment to their bosses.

Machines, but also trains and trucks are full of sensors to monitor their functioning. Traffic is tracked with sensors of all kinds which measure among many others the quantity of exhaust gases and particulate matter. In many places in the world, people are be monitored with hundreds of thousands CCTV’s. A simple signature from American owners of a Ring doorbell is enough to pass on to the police the countenance of those who come to the front door. Orwell couldn't have imagined.

Privacy

Internet of Things makes it possible to always track every person, inside and outside the home. When it comes to collecting data in-house, the biggest problem is obscurity and lack of transparency. Digital home-law can be a solution, meaning that no device collects data unless explicit permission is given. A better solution is for manufacturers to think about why they want to collect all this data at all.

Once someone leaves the house, things get trickier. In many Dutch cities 'tracking' of mobile phones has been banned, but elsewhere a range of means is available to register everyone's (purchasing) behavior. Fortunately, legislation on this point in Europe is becoming increasingly strict.

Autonomy

The goal of constant addition of more 'gadges' to devices and selling them as 'smart' is to entice people to buy them, even if previous versions are far from worn out. Sailing is surrounded by all of persuasive techniques that affect people's free will. Facebook very deftly influences our moods through the selection of its newsfeeds. Media, advertisers, and companies should consider the desirability of taking a few steps back in this regard. For the sake of people and the environment.

Safety

Sensors in home appliances use to be poorly secured and give cybercriminals easy access to other devices. For those who want to control their devices centrally and want them to communicate with each other’s too, a closed network - a form of 'edge computing' - is a solution. Owners can then decide for themselves which data may be 'exposed', for example for alarms or for balancing the electricity network. I will come back to that in a later episode.

Control

People who, for example, control the lighting of their home via an app, are already experiencing problems when the phone battery is empty. Experience also shows that setting up a wireless system is not easy and that unwanted interferences often occur. Simply changing a lamp is no longer sufficient to solve this kinds of problems. For many people, control over their own home slips out of their hands.

Power relations

The digital component of many devices and in particular the dependence on well-configured software makes people increasingly dependent on suppliers, who at the same time are less and less able to meet the associated demand for service and support.

2. Robotics

Robotics is making its appearance at great speed. In almost every heart surgery, robotics is used to make the surgeon's movements more precise, and some operations are performed (almost) completely automatically. Robots are increasingly being used in healthcare, to support or replace healthcare providers. Also think of robots that can observe 3D and crawl through the sewage system. They help to solve or prevent leakages, or they take samples to detect sources of contamination. Leeds aims to be the first 'self-repairing city' by 2035. ‘Self-driving' cars and metro trains are other examples. Most warehouses and factories are full of robots. They are also making their appearance in households, such as vacuum cleaners or lawnmowers. Robots transmit large amounts of information and are therefore essential parts of the Internet of Things.

Privacy

Robots are often at odds with privacy 'by design'. This applies definitely to robots in healthcare. Still, such devices are valuable if patients and/or their relatives are sufficiently aware of their impact. Transparency is essential as well as trust that these devices only collect and transmit data for the purpose for which they are intended.

Autonomy

Many people find 'reversing parking' a problem and prefer to leave that to robotics. They thereby give up part of their autonomous driver skills, as the ability to park in reverse is required in various other situations. This is even more true for skills that 'self-driving' cars take over from people. Drivers will increasingly find themselves in situations where they are powerless.

At the same time, robotics is a solution in situations in which people abuse their right to self-determination, for example by speeding, the biggest causes of (fatal) accidents. A mandatory speed limiter saves untold suffering, but the 'king of the road' will not cheer for it.

Safety

Leaving operations to robots presupposes that safety is guaranteed. This will not be a problem with robotic lawnmowers, but it is with 'self-driving cars'. Added to this is the risk of hacking into software-driven devices.

Human dignity

Robots can take over boring, 'mind-numbing' dangerous and dirty work, but also work that requires a high degree of precision. Think of manufacturing of computer chips. The biggest problems lie in the potential for job takeovers, which not only has implications for employment, but can also seriously affect quality. In healthcare, people can start to feel 'reified' due to the loss of human contact. For many, daily contact with a care worker is an important instrument against loneliness.

3. Biometrics

Biometrics encompasses all techniques to identify people by body characteristics: iris, fingerprint, voice, heart rhythm, writing style and emotion. Much is expected of their combination, which is already applied in the passport. There is no escaping security in this world, so biometrics can be a good means of combating identity fraud, especially if different body characteristics are used.

In the US, the application of facial recognition is growing rapidly. In airports, people can often choose to open the security gate 'automatically’ or to stand in line for security. Incode, a San Francisco startup, reports that its digital identity recognition equipment has already been used in 140 million cases by 2021, four times as many as in all previous years combined.

Privacy

In the EU, the privacy of residents is well regulated by law. The use of data is also laid down in law. Nevertheless, everyone's personal data is stored in countless places.

Facial recognition is provoking a lot of resistance and is increasingly being banned in the public space in the US. This applies to the Netherlands as well.

Biometric technology can also protect privacy by minimization of the information: collected. For example, someone can gain access based on an iris scan, while the computer only checks whether the person concerned has authorization, without registering name.

Cyber criminals are becoming more and more adept at getting hold of personal information. Smaller organizations and sports clubs are especially targeted because of their poor security. If it is also possible to obtain documents such as an identity card, then identity fraud is lurking.

Safety

Combining different identification techniques as happens in passports, contributes to the rightful establishing someone's identity. This also makes counterfeiting of identity documents more difficult. Other less secured documents, for example driver's licenses and debit cards, can still be counterfeited or (temporarily) used after they have been stolen, making identity theft relatively easy.

Human dignity

The opposition to facial recognition isn't just about its obvious flaws; the technology will undoubtedly improve in the coming years. Much of the danger lies in the underlying software, in which bias is difficult to eliminate.

When it comes to human dignity, there is also a positive side to biometrics. Worldwide, billions of people are unable to prove who they are. India's Aadhar program is estimated to have provided an accepted form of digital identity based on biometrics to 1.1 billion people. The effect is that financial inclusion of women has increased significantly.

Justice

In many situations where biometric identification has been applied, the problem of reversed burden of proof arises. If there is a mistaken identity, the victim must prove that he is not the person the police suspect is.

To be continued next week.

The link below opens an overview of all published and future articles in this series. https://www.dropbox.com/s/vnp7b75c1segi4h/Voorlopig%20overzicht%20van%20materialen.docx?dl=0

Ethical principles and artificial intelligence

In the 11th episode of the series Better cities: The contribution of digital technology, I will apply the ethical principles from episode 9 to the design and use of artificial intelligence.

Before, I will briefly summarize the main features of artificial intelligence, such as big data, algorithms, deep-learning, and machine learning. For those who want to know more: Radical technologies by Adam Greenfield (2017) is a very readable introduction, also regarding technologies such as blockchain, augmented and virtual reality, Internet of Things, and robotics, which will be discussed in next episodes.

Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence has valuable applications but also gross forms of abuse. Valuable, for example, is the use of artificial intelligence in the layout of houses and neighborhoods, taking into account ease of use, views and sunlight with AI technology from Spacemaker or measuring the noise in the center of Genk using Nokia's Scene Analytics technology. It is reprehensible how the police in the US discriminate against population groups with programs such as PredPol and how the Dutch government has dealt in the so called ‘toelagenaffaire’.

Algorithms

Thanks to artificial intelligence, a computer can independently recognize patterns. Recognizing patterns as such is nothing new. This has long been possible with computer programs written for that purpose. For example, to distinguish images of dogs and cats, a programmer created an "if....then" description of all relevant characteristics of dogs and cats that enabled a computer to distinguish between pictures of the two animal species. The number of errors depended on the level of detail of the program. When it comes to more types of animals and animals that have been photographed from different angles, making such a program is very complicated. In that case, a computer can be trained to distinguish relevant patterns itself. In this case we speak of artificial intelligence. People still play an important role in this. This role consists in the first place in writing an instruction - an algorithm - and then in the composition of a training set, a selection of a large number of examples, for example of animals that are labeled as dog or cat and if necessary lion tiger and more . The computer then searches 'itself' for associated characteristics. If there are still too many errors, new images will be added.

Deep learning

The way in which the animals are depicted can vary endlessly, whereby it is no longer about their characteristics, but about shadow effect, movement, position of the camera or the nature of the movement, in the case of moving images. The biggest challenge is to teach the computer to take these contextual characteristics into account as well. This is done through the imitation of the neural networks. Image recognition takes place just like in our brains thanks to distinguishing layers, varying from distinguishing simple lines, patterns, and colors to differences in sharpness. Because of this layering, we speak of 'deep learning'. This obviously involves large data sets and a lot of computing power, but it is also a labor-intensive process.

Unsupervised learning

Learning how to apply algorithms under supervision produces reliable results and the instructor can still explain the result after many iterations. As the situation becomes more complicated and different processes are proceeding at the same time, guided instruction is not feasible any longer. For example, if animals attack each other, surviving or not, and the computer must predict which kind of animals have the best chance of survival under which conditions. Also think of the patterns that the computer of a car must be able to distinguish to be able to drive safely on of the almost unlimited variation, supervised learning no longer works.

In the case of unsupervised learning, the computer is fed with data from many millions of realistic situations, in the case of cars recordings of traffic situations and the way the drivers reacted to them. Here we can rightly speak of 'big data' and 'machine learning', although these terms are often used more broadly. For example, the car's computer 'learns' how and when it must stay within the lanes, can pass, how pedestrians, bicycles or other 'objects' can be avoided, what traffic signs mean and what the corresponding action is. Tesla’s still pass all this data on to a data center, which distills patterns from it that regularly update the 'autopilots' of the whole fleet. In the long run, every Tesla, anywhere in the world, should recognize every imaginable pattern, respond correctly and thus guarantee the highest possible level of safety. This is apparently not the case yet and Tesla's 'autopilot' may therefore not be used without the presence of a driver 'in control'. Nobody knows by what criteria a Tesla's algorithms work.

Unsupervised learning is also applied when it comes to the prediction of (tax) fraud, the chance that certain people will 'make a mistake' or in which places the risk of a crime is greatest at a certain moment. But also, in the assessment of applicants and the allocation of housing. For all these purposes, the value of artificial intelligence is overestimated. Here too, the 'decisions' that a computer make are a 'black box'. Partly for this reason, it is difficult, if not impossible, to trace and correct any errors afterwards. This is one of the problems with the infamous ‘toelagenaffaire’.

The cybernetic loop

Algorithmic decision-making is part of a new digital wave, characterized by a 'cybernetic loop' of measuring (collecting data), profiling (analyzing data) and intervening (applying data). These aspects are also reflected in every decision-making process, but the parties involved, politicians and representatives of the people make conscious choices step by step, while the entire process is now partly a black box.

The role of ethical principles

Meanwhile, concerns are growing about ignoring ethical principles using artificial intelligence. This applies to near all principles that are discussed in the 9th episode: violation of privacy, discrimination, lack of transparency and abuse of power resulting in great (partly unintentional) suffering, risks to the security of critical infrastructure, the erosion of human intelligence and undermining of trust in society. It is therefore necessary to formulate guidelines that align the application of artificial intelligence again with these ethical principles.

An interesting impetus to this end is given in the publication of the Institute of Electric and Electronic Engineers: Ethically Aligned Design: A Vision for Prioritizing Human Well-being with Autonomous and Intelligent Systems. The Rathenau Institute has also published several guidelines in various publications.

The main guidelines that can be distilled from these and other publications are:

1. Placing responsibility for the impact of the use of artificial intelligence on both those who make decisions about its application (political, organizational, or corporate leadership) and the developers. This responsibility concerns the systems used as well as the quality, accuracy, completeness, and representativeness of the data.

2. Prevent designers from (unknowingly) using their own standards when instructing learning processes. Teams with a diversity of backgrounds are a good way to prevent this.

3. To be able to trace back 'decisions' by computer systems to the algorithms used, to understand their operation and to be able to explain them.

4. To be able to scientifically substantiate the model that underlies the algorithm and the choice of data.

5. Manually verifying 'decisions' that have a negative impact on the data subject.

6. Excluding all forms of bias in the content of datasets, the application of algorithms and the handling of outcomes.

7. Accountability for the legal basis of the combination of datasets.

8. Determine whether the calculation aims to minimize false positives or false negatives.

9. Personal feedback to clients in case of lack of clarity in computerized ‘decisions’.

10. Applying the principles of proportionality and subsidiarity, which means determining on a case-by-case basis whether the benefits of using artificial intelligence outweigh the risks.

11. Prohibiting applications of artificial intelligence that pose a high risk of violating ethical principles, such as facial recognition, persuasive techniques and deep-fake techniques.

12. Revocation of legal provisions if it appears that they cannot be enforced in a transparent manner due to their complexity or vagueness.

The third, fourth and fifth directives must be seen in conjunction. I explain why below.

The scientific by-pass of algorithmic decision making