Radically different collaboration on transitions

One crisis will follow another in the next decade, and all transitions will get stuck. That is the prediction of DRIFT researchers Jan Rotmans and Gijs Diercks in this essay. Only a drastically different approach to permanent problems could still turn the tide.

We live in a time of chaos, marked by semi-permanent crises, not only worldwide, but also in Europe and in the Netherlands. The very Netherlands that once seemed so well organised is getting stuck in many areas: nitrogen, nature, construction, Schiphol, energy, climate, mobility, healthcare. The root causes of this have to do with inadequate governance, lack of leadership and perseverance, but above all the eternal poldering (consensus-based decision-making). Poldering has brought us much good, but it does not help address intractable problems. These call for radical solutions. Because pseudo-solutions become part of the problem in no time. Many files have been shelved for decades to delay the transition pain as long as possible. We see this in all transition themes that the Amsterdam Economic Board is committed to, such as energy, circularity and mobility.

Energy crisis due to naive belief in business as usual

The current energy crisis is a wake-up call for our gas dependence on Russia. For too long we have been lulled to sleep by our own natural gas supplies. If those would run out, we even planned to create a ‘gas traffic circle’ and become a hub in the European gas trade. In it, Russia would become the primary gas supplier, a reliable partner because, ‘Russia always delivers’. Nowadays, it’s clear how naive the Netherlands was. Hastily, we had to look for alternatives (at great cost), such as liquefied natural gas. In fact, we are now being forced to run coal-fired power plants longer and more often. This illustrates the stagnant construction and breakdown of the Dutch energy system. We started too late with building an infrastructure for renewable energy, such as solar and wind. Had we done that earlier we wouldn’t be in trouble now. The decomposition of fossil energy was also stagnant: we should have focused much earlier and much more on energy conservation, both in industry and households. Too late we have recognised our gas dependence, and with it the importance of the geopolitical dimension in the energy transition.

Raw materials transition in its infancy

And this is just the beginning. The real transition – the raw materials transition – is yet to start. Raw materials are prerequisites for the energy transition. If we want to switch to solar panels, wind turbines and electric cars on a large scale, we need a lot of critical metals, such as lithium, silicon, scandium, neodymium, dysprosium, gadolinium and lanthanum. China owns more than half of the stocks of these metals and controls 95% of world production. Demand for these critical metals is expected to skyrocket in the coming years. And with it, the price. A price increase of 1,000% over the next decade is quite conceivable.

We now waste about 93% of our resources and in the continuous extraction of new resources we destroy a lot of natural capital. In the foreseeable future that will become too costly given rising prices. Especially in light of the looming ‘sustainable waste mountain’, as first-generation solar panels, wind turbines and batteries are replaced by more efficient ones. The Netherlands will have installed 80 million solar panels by 2024, with limited capacity for replacement or recycling. A huge destruction of capital, forcing us to move faster to a circular economy. That transition is still about 15 years behind the energy transition.

For that circular transition, the building and breaking down of systems has barely begun. Quite a few laws and regulations stand in the way of the circular transition. Like the waste law, which prohibits companies from recycling waste. Linear financing, which focuses primarily on construction but does not sufficiently consider maintenance and end-of-life, is also a major obstacle to the circular transition. It needs to be replaced by circular finance which considers broader circular metrics and also better incorporates the risks of linear finance into financing decisions.

The circular transition is a profound change that includes thinking, designing, organising, financing and managing differently. The entire resource chain is shaking up, and regions are the foundation of a new, circular economy. Complete autonomy is unachievable, but as much as possible is a useful aspiration. This is where the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area has an important role to play, as a supra-local scale where city and surrounding areas are connected is critical to circulating sufficient energy, raw materials, food, knowledge and expertise.

Mobility: all arrows aimed at overshoot collapse

There is not yet a mobility crisis in the Netherlands, but that is only a matter of time. The motorways are again as busy as they were before corona. If we continue like this, in 10 years time the Netherlands will be completely locked in one big traffic jam. Admittedly a cleaner, quieter traffic jam, because of the high proportion of electric cars. There is a lack of an integrated mobility policy, with optimal coordination between different transportation options. The Randstad area is developing towards a large Metropolis. These thrive on public transportation in terms of mobility: metro, bus, trams and train, supplemented by cars. Except in the Randstad Metropolis, where the car is still central. Within cities such as Amsterdam, Utrecht and Rotterdam, a turn towards car-free streets is noticable. There are policies, focused on car sharing, priority for bicycles as well as electric and smart mobility. Still, the number of cars is only increasing.

Nationwide, the opposite of what is needed is happening, with a dismantling of the public transportation system through a variety of budget cuts. What we should strengthen, we break down (public transport) and what we should break down (automobility), we strengthen by building more and more roads. This cannot fail to lead, in transition terms, to an overshoot collapse, in which the system completely crashes within the foreseeable future.

For the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area, multimodal mobility – offering a choice of transportation options – is critical. We know what is needed for this, such as fair pricing of automobility through road pricing. But for decades now, this has been delayed by the national government. Recently, policy-making on this topic has being passed on to 2030. Amsterdam is leading the way in breaking down automobility, introducing strict environmental zones and removing more and more parking spaces. But that is certainly not the case for the Amsterdam region, where a clear vision and strategy for mobility is still lacking.

Other ways of working together

The themes at play within energy, circular economy and mobility all point in only one direction: the next decade will be marked by crises. On every conceivable transition theme we are going to get stuck, including in the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area. This requires a radically different method and approach. No more poldering and compromise, but creating support from an authoritative platform for a radical change agenda on all these issues.

There are three main prerequisites for this collaboration:

A common vision of the future: To work successfully on transition, the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area must start from a common vision of the future to work on a desired transition: fundamental change in thinking, organising and acting towards a sustainable and just future. The stakes must go beyond collaborating on innovation. In addition to building up, breaking down belongs on the agenda too. Where are the coalitions that make car-free the norm, not just for inner cities, but for the entire metropolis? What pact can we forge to stop linear building practices? How do we get and keep energy conservation less non-committal on the agenda?

New, surprising transition coalitions: Working on decomposition requires other types of collaboration. Beyond the innovation-oriented triple helix, but focused on new surprising transition coalitions. Bold demolition projects require unusual coalitions, in which businesses and governments commit to the radical ambitions of civil society organisations to act together to overturn the system. Consider the protest movement in the 1970s that successfully managed to put the dominance of the automobile on the agenda, which turned into policies that made Amsterdam’s inner city livable again. The scale of the Amsterdam Metropolis – between municipalities and the state and across provincial borders – lends itself perfectly to forging this kind of unusual coalition.

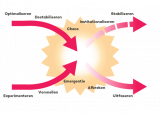

Leaders with guts and vigor: Finally, there is a need for a different type of person. Not innovation managers or opportune networkers, but a diversity of transition roles: leaders, scale-tippers, connectors and demolishers. People who couple a sense of urgency and personal drive with decisiveness and guts, courage and leadership. Working on transition can be done in several ways. It is important that they help and strengthen each other. The Amsterdam Economic Board can play an important role in this regard. Organisations, in addition to embracing the vision outlined above, will also need to work to delegate the right people to the Board. These people must be given enough trust, support and organisational mandate to turn difficult projects into a success.

The question is whether these characteristics are currently sufficiently present. Traditionally, the Board has reflected the existing system, but we see how the Amsterdam Economic Board is repositioning itself, claiming an agenda-setting role in the new economy. The themes and ways of working together are also changing. As a positive example, we cite the cry for help from Alliander, which put the issue of grid congestion on the Board’s table at an early stage. With a clear call: the energy grid is gridlocked, and alone we cannot fix this. This was not a call for a polder solution but a request for help from vulnerability and confidence that the Board could provide the important intervening space to quickly and thoroughly address this problem together.

For now, grid congestion has not yet been resolved. The Amsterdam Economic Board and its network will still have to prove whether they can play the crucial role to get us through a decades of crises. As we have argued in this essay – as well as in our previous essays Beyond the triple helix and Come on, stumble – this requires a substantial change in both the structure, culture and working methods of the Amsterdam Economic Board and its partners. We wish you every success in this, because the stakes are high.

Written by: Gijs Diercks en Jan Rotmans