The Kaskantine will implement together with the neighboorhood its design for closing local resource loops: a kitchen with closed water cycle, preventing local food waste, introduce neighbourhood composting, and organise repair cafe's, sport and musique workshops, etc. Data will be gathered to monitor the resource cycling and methods will be tested to make it more socially and culturally inclusive.

User-created nature-based solutions in an urban environment;

The case of the KasKantine (Greenhouse Cantina), Amsterdam

Historically landscape architecture and infrastructural planning have assigned physical separated functions to landscape in order to upscale and manage resource flows cost efficiently. Rather than monosectoral and large scale linear production systems we can now see a shift to decentralized and locally integrated solutions to close resource loops. In these solutions also citizens can play a more (pro)active role. After being more prominent in rural areas, landscape architecture is now also more active as a lead design principle in urban neighbourhoods. Local integrated solutions for resource cycling efficiency give rise to multiple value production rather than to an increase of local financial income. Either way it increases citizen driven (semi)professional activities in resource management in urban neighbourhoods, as well in its creation and in management.

We see enormous potential in this approach: it can reconnect citizens to nature, it can facilitate in changing lifestyles AND produce the right technology to face our climate and resource crisis. But before it can become mainstream, we see the following challenges and questions, mainly to do with creating sufficient local political support and accessibility to these technological and economic opportunities.

- How can actors on local level on one side and central sectoral level at the other side co-create and redesign effectively the landscape, necessary to close resource loops locally with sufficient democratic legitimacy?

- How could citizen-driven services in resource management be held accountable to a broader public and the public sector?

- How can these nature-based solutions be culturally and socially inclusive?

- How can socio-economically marginal(ized|) groups profit from this increased multiple-values production?

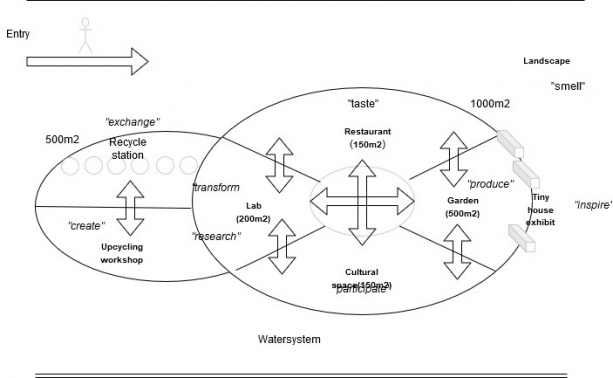

We can try to answer those questions for one specific case to see how it could work out in practice. The Kaskantine is a not-for-profit volunteer driven garden- restaurant - food coop which has as its main objective to show that more autonomous, off the grid nature based solutions for climate adaptive working and living in urban areas are possible and can be at the same time a new lifestyle. It is a small village of refurbished shipping containers, recycled greenhouses and (roof top)gardens. The Kaskantine is currently being built on its fourth location and is negotiating a 7 years ground lease with the municipality of Amsterdam.

The Kaskantine managed to grow from only one container and a one-man company, 5 years ago, to a cooperative with over 30 volunteers with 13 containers. A second village is being planned of 7 containers in the east of Amsterdam. This has been realised without any external capital investment or subsidies. The strategy has always been: find a solution with the least possible financial costs and turn untapped local resources into value.

In doing so the Kaskantine discovered that although real estate prices in Amsterdam skyrocket, there is still a lot of underutilised land and water, that is without use for people and for nature. Lots of plots are “waiting” to be developed, or are underdeveloped: for one function while there could be double or triple functionalities. We could call this “real estate waste”. The Kaskantine could use land for free because there was no direct market value of that land. And the same counts for other important resources: (rain)water, (solar)energy, food (waste and own production), labour (volunteers) and (natural and waste) materials. The Kaskantine is able to operate with zero fixed costs and therefore able to survive.

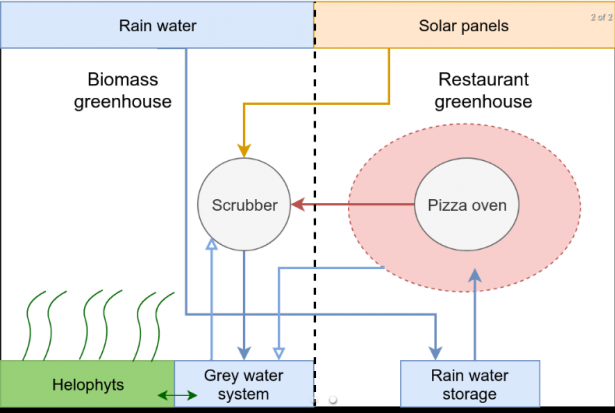

Furthermore, with its installations it is trying to integrate all received good and services in local loops. Maximum in, minimum out. This is optimized by integrating different resource loops in one management system.

An abundance of one flow of resources can be absorbed by other resource cycles: Peak solar energy can be used in extra ventilation, aeration and irrigation. Sudden food surpluses are redistributed for free and create network solidarity. The Kaskantine is also able to use resources in all phases of their life cycle, like wood: from construction to fire wood. Or being able by using rest heat in storing it in mass or other spaces, or filtering waste water for irrigation. We call this adaptive capacity: the capacity to buffer abundance and use it later or in an alternative way.

Finally, an alternative lifestyle is embraced, one that is appreciating the value of abundance of local resources, rather than the value of market choice.

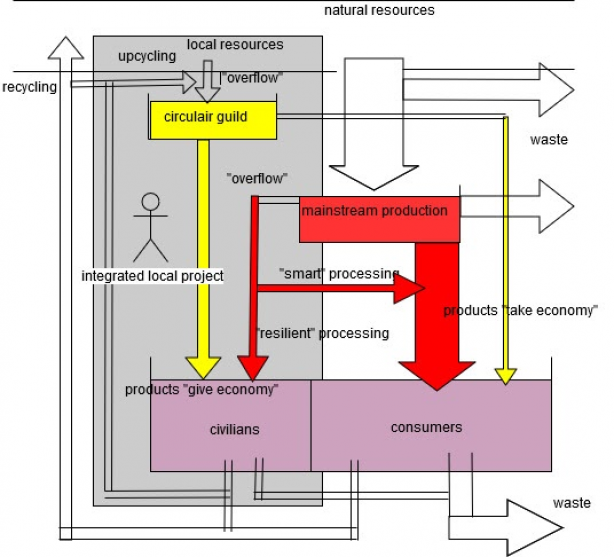

We could argue that the Kaskantine is thriving in an alternative economy, that can exist thanks to and despite of the mainstream economy that they are trying to transform. We call this abundance or give economy, in contrast with economy based on consumption and the organisation of scarcity.

Abundance economy as being a sum of relatively autonomous integrated projects in mainstream economy.

Because of its ability to expand autonomously within mainstream economy, and because its abundance economy is not a zero-sum game as long as local resources and waste are underutilised, the Kaskantine is very open for participation. There is no economic argument against including more neighborhood activities, on the contrary. More participation seems therefore to depend more on the capability of cultural inclusiveness: if people feel comfortable within the network of the Kaskantine, or if people feel comfortable to start a sort of “kaskantine” on their own.

First, the opportunity to integrate has been ”built in” into the design of the Kaskantine by a step-in approach. From experience as a guest (exchange, tasting, get inspired, etc) to participation in the design, creation and operation of the Kaskantine and Kaskantine related projects.

Secondly, the Kaskantine is also active in the neighbourhood centre and within a network of community organisations, with a step-out approach. In this case the Kaskantine offers through free workshops a learning curve to adopt small scale installations, like vertical gardens and worm composting, and participate in food saving and storage at home in order to take a step back from mainstream economy into the abundance economy.

An important ambition of the Kaskantine is to negotiate with the municipality a land lease contract in which the landuser takes responsibility for its development and environmental control of the land. This cheaper land rent will hopefully give other “kaskantines” the opportunity to arise.

The Kaskantine has free energy to spend on helping other groups in joining this movement because it can operate autonomously and with low fixed costs. This creates hopeful opportunities for inclusiveness of the proposed solutions. Whether this is done in some kind of co-creation with more central institutions depends more on their own capability to work with local small scale initiatives and on their willingness to change or compensate the negative effects of their lineair production models and on their willingness and capability to change sectoral into integrated policies.