Stay in the know on all smart updates of your favorite topics.

Demoday #28: From Policy to Practice: Inclusive Design Ambitions of the Amsterdam Transport Authority

On the 5th of June, during the 28th Knowledge and Demo Day, we explored the topic of Inclusive Design in the context of mobility projects together with a diverse group of network partners. Iris Ruysch introduced the theme on behalf of the Amsterdam Transport Authority (Vervoerregio), while David Koop and Lotte de Wolde from our knowledge partner Flatland facilitated the session format, moderation and visual notes.

The ambition of the Amsterdam Transport Authority

The Amsterdam Transport Authority is responsible for public transport across fourteen municipalities in the region and is working towards a mobility system that enables people to travel quickly, safely and comfortably by public transport, bicycle or car. In addition to organising and funding public transport and investing in infrastructure, the Authority actively contributes to broader societal goals such as sustainability, health and inclusivity.

Inclusive mobility is one of the key themes within the wider mobility policy. The central principle is that everyone – regardless of age, income, disability, gender or background – should be able to travel well and comfortably throughout the region. This calls for a mobility system that is accessible, affordable, appropriate, socially safe and welcoming.

The aim of the session on 5 June was to work with the network towards an initial action plan for applying inclusive design principles in mobility projects. Iris is keen to ensure that the ambitions around inclusivity are not only stated in policy and vision documents but are truly embedded in the organisation – from policymakers to implementation teams.

Session set-up

After an introduction by Iris on the context and ambitions within the Transport Authority, we got to work. In small groups, participants explored the profile of the implementing civil servant (using a persona canvas) and considered desirable changes in approach; in terms of attitude, skills and collaboration.

We then used the Inclusive Design Wheel to examine how existing programme components of the Authority could be made more inclusive. In pairs, we tackled themes such as accessible travel information, social safety at stations (specifically for women), and improving bicycle parking facilities.

The Inclusive Design Wheel is an iterative process model that supports the structural integration of inclusivity into design and policy projects. The model emphasises collaboration, repetition, and continuous learning. It consists of four phases:

- Explore: Gather insights about users, their needs, and potential exclusion.

- Create: Develop ideas, concepts, and prototypes that address inclusive needs.

- Evaluate: Test whether the designs are inclusive, collect feedback, and make improvements where necessary.

- Manage: Ensure shared understanding, set goals, engage stakeholders, and embed the process.

Outcomes and insights

While the persona profiles were being developed, I observed the group discussions and noted several important insights to take forward in the development of the action plan:

- Awareness and concrete translation: Implementation teams often already have an intrinsic motivation to contribute to inclusivity goals set in policy. However, they may not always realise how their day-to-day work can support those goals. It’s important to continuously ask the question ‘How, exactly?’. Tools like checklists, templates and practical examples can support this translation from policy to practice.

- Flexible guidelines and not ‘extra work’: Given the differences in scale, pace and content of projects, guidelines need to be flexible. There must also be sufficient room in terms of time and budget. Most importantly, these guidelines and action plans should feel supportive, not like extra rules or bureaucracy. Too many rigid frameworks can backfire.

- Interaction between policy and implementation: There is a need for more two-way communication. Implementation teams want to be involved early in policy development, especially when they will be the ones carrying it out. They also want opportunities to reflect with policymakers on whether policy is being implemented as intended. This allows for timely feedback and course-correction based on real-world experience.

- An Inclusive Design mindset: Beyond sharpened policy documents and a stronger focus on the end user, Inclusive Design also requires a mindset – one that is inquisitive and reflective. Embedding this within the organisational culture will require more than just an action plan.

What’s next

Iris collected valuable input to kick-start the development of the action plan, and participants gained a better understanding of the Amsterdam Transport Authority, the principles of Inclusive Design, and what it takes to move from policy to implementation. This summer, a trainee will start at the Transport Authority to further develop this topic and the action plan. The session, this report, and Flatland’s visual notes provide a strong foundation to build on. We’ll be meeting with Iris and David to explore how we can support this follow-up.

Would you like to learn more about any of the topics or developments mentioned in this report? Feel free to email pelle@amsterdaminchange.com.

🚨 𝗪𝗲'𝗿𝗲 𝗮𝗹𝗿𝗲𝗮𝗱𝘆 𝗮𝘁 𝟱𝟬% – 𝗮𝗻𝗱 𝘄𝗲 𝗵𝗮𝘃𝗲𝗻'𝘁 𝗲𝘃𝗲𝗻 𝗸𝗶𝗰𝗸𝗲𝗱 𝗼𝗳𝗳 𝘆𝗲𝘁! 🚨

Wow! Half of the tickets for our Cenex Nederland Lenteborrel have already been ordered – and the event isn’t even happening until 8th of May 2025. 🎉

That means: lots of excitement, high expectations, and... an opportunity you don’t want to miss.

The event will be focusing on Transport & Mobility, Circular Mobility, Energy & Infrastructure, where you can expect the following.

📍 What to expect:

✅ Meet exhibitors and explore the latest innovations

🎮 Join or watch two exciting serious game sessions

🎤 Be inspired by four engaging keynotes (English)

🥂 End the day with our annual spring reception where you have the opportunity to network.

Want to join us? Don’t wait too long – the remaining 50% is likely to go even faster. 🎫

Please make sure to get your (free) ticket via Eventbrite

Demoday #25: Scenarios for Smart Mobility in the Province of North Holland 2050

During our Knowledge and Demo Day on 10 October (2024), Guus Kruijssen and Rombout Huisman (Province of North Holland) led a working session on their recent scenario studies – Smart Mobility North Holland 2050. In this report, I will share the four ‘Context’ scenarios they developed, the process, and the discussions with the session participants.

Objectives of the Scenario Study

What do we actually mean by future visions and scenarios? What are the different types, and how can they be used? A discussion among the participants quickly highlighted the many different motivations, forms, and use cases. Rombout and Guus began by explaining their aim for this study.

The province of North Holland plays various roles in the field of mobility as a policymaker, road manager, and concession provider. Given the major challenges related to housing, CO2 emissions reduction, and road safety, their perspective on the future of mobility revolves around Reducing (travel), Improving (travel options), and Changing (travel behaviour). This perspective forms the basis for developing, operationalising, and maintaining their strategy – a cycle that spans approximately 50 years. However, digital developments and innovations are making the world change faster than ever, necessitating greater awareness of possible contextual changes. The key question is: how do the choices we make now relate to the different possible futures?

To explore this, a team of colleagues embarked on developing four challenging context scenarios. Working with internal and external experts, they moved from an environmental analysis and contextual factors to scenarios and strategic insights. The process and outcomes were kept administrative and had no political or policy-driven focus. The result is not a set of visions to choose from but rather a representation of various developments and challenges that may arise, to which you can assess your own projects and actions against.

The Four Scenarios

Four distinct context scenarios were developed. Here is a summary and a few key aspects of each:

- Steady Traffic (Doorgaand verkeer) A slow shift towards a green economy, benefiting only the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area (MRA). The population grows to 3.7 million. Cars remain dominant, transitioning gradually to electric, but roads and trains stay congested. Digitalisation and innovation progress slowly, with limited impact on efficiency and accessibility.

- Turbulent Weather (Rukwinden) Ongoing shocks and international instability, with the US leaving NATO and significant climate change. The population increases to 3.1 million. Fuel crises accelerate electrification, but investment focuses on priorities like the navy. Technological scepticism grows due to data breaches, impacting accessibility.

- Our Own Path (Eigen weg) The Netherlands withdraws from international cooperation and leaves the EU, focusing on healthcare, circularity, and local production. The economy contracts due to trade restrictions and brain drain, and the population decreases to 2.6 million. Fewer traffic jams, but cars remain significant alongside increased regional public transport. Distrust in innovations and sustainability rises, with informal sharing preferred over commercial options.

- Transition (Overstappen) Climate change accelerates transition and AI development. The population stabilises at 3.1 million. Non-sustainable sectors disappear, and reduced traffic results from digitalisation and virtualisation. Space is primarily used for energy infrastructure, and circular processes increase. The EU and the national government push for innovations like autonomous transport and shared mobility. Ownership is limited to the wealthiest, and digital infrastructure becomes a priority.

Outcomes and Follow-Up

Rombout and Guus guided the group through the process and results of these scenario studies. We discussed the developments and contextual factors used in the study, and considered if anything was missing. They openly shared their approach and how they plan to use these insights to assess their own policies and projects, and welcomed questions and suggestions from the group. There was also room for discussing the challenges. Because, while people can easily align on scenarios, opinions can still vary greatly on how we should act on them now.

Many of our partners are already working with future visions and scenarios. See, for instance, our report on a session with trendwatchers from the Municipality of Amsterdam. The purpose, process, and impact on policy, projects, and actions vary across organisations. However, there was agreement that sharing methods and scenarios is valued, particularly in a neutral setting like our innovation network. It fosters mutual understanding and offers valuable lessons from each other's research methods and practical applications. In the coming period, we will explore how we can contribute to this in our network on various transition themes.

Would you like to know more about this study from the Province of North Holland? Feel free to send me a message, and I will connect you. Interested in brainstorming about how we can approach this more frequently or systematically within the network? Let me know at pelle@amsterdaminchange.com.

De Interdisciplinaire Afstudeerkring - Mobiliteitsrechtvaardigheid. HvA x PNH x ASC

ENGLISH BELOW

Gedurende de eerste helft van 2024 werkten we samen met vier studenten van de Hogeschool van Amsterdam (HvA) op het thema Mobiliteitsrechtvaardigheid. Samen met de provincie Noord-Holland waren we als opdrachtgevers onderdeel van een primeur: De eerste interdisciplinaire afstudeerkring van de Hogeschool van Amsterdam. De afstudeerders kwamen vanuit verschillende opleidingen. De groep van vier bestond uit twee Bestuurskunde studenten (Jade Salomons en Timo van Elst), een student Toegepaste Psychologie (Jackie Ippel), en een student Communicatie en Multimedia Design (Merel Thuis).

De HvA wilt haar studenten al vroeg bekend maken met interdisciplinair samenwerken en onderzoeken. Een domein-overstijgend en complex vraagstuk als Mobiliteitsrechtvaardigheid, wat al langere tijd binnen het Amsterdam Smart City netwerk wordt behandeld, bleek een mooi onderwerp voor hun eerste afstudeerkring. Voor zowel de HvA en de opdrachtgevers was er veel nieuw aan dit project en waren er veel onzekerheden, maar vanuit onze waarde ‘leren door te doen’ gingen we samen aan de slag!

Resultaten

Na een kick-off met de leden van de Mobiliteitsrechtvaardigheid werkgroep en verkennende interviews met specialisten van Provincie Noord-Holland vormden de studenten concrete onderzoeksvragen. Na een brede introductie en vraagstelling hebben de studenten een deelonderwerp eigen gemaakt en hun afstudeeropdracht daarop ingericht. Bij deze licht ik kort toe wat de verschillende onderwerpen en resultaten waren. Bij vervolgvragen kunnen jullie mij of Bas Gerbrandy (PNH) een berichtje sturen.

- Timo keek naar het grotere plaatje en bestudeerde hoe het mobiliteitsbeleid in Noord-Holland nu is ingericht, met name met betrekking tot Mobiliteitsarmoede. Ook keek hij hoe participatiemethoden hier nu een rol in had. Hij schreef een advies waarin hij bijvoorbeeld pleit voor het installeren van participatie experts per domein/sector, in plaats van het als een apart team beschouwen.

- Jackie verdiepte zich nog meer in hoe ambtenaren zich verhouden tot de doelgroep die mobiliteitsarmoede kan ervaren. Zij onderzocht de bereidheid van ambtenaren om in gesprek te gaan met de doelgroep. Een belangrijk onderdeel wat velen nog een spannend idee vinden. Ook hielp Jackie mee met Jade’s focusgroep en kwalitatieve onderzoek.

- Jade ging namelijk het veld in. Ze sprak ouderen in Purmerend over hun reiservaringen en wat voor belemmeringen ze ervaren. Haar onderzoek bewees hoe belangrijk dit onderdeel is. Ze lichtten bijvoorbeeld uit dat ouderenvervoer goed geregeld is, maar dat ze angstig kunnen zijn tijdens hun reisbewegingen. Slechte kwaliteit van voetpaden en het snelle optrekken van een bus is waar ze het veel over wilden hebben.

- Ten slotte ging Merel aan de slag met een multidevice ontwerp. Ze creëerde een tool waarmee belevingen van inwoners op persoonlijk niveau uitgevraagd kunnen worden. Vervolgens wordt hierin inzichtelijk en tastbaar gemaakt wat beleidsrisico’s en -kansen zijn voor de sector Mobiliteit van de provincie. Het dient zo als gesprekstool en brug tussen de persoonlijke ervaringen van inwoners en de abstractere en strategische niveau van de beleidsmedewerkers.

Interdisciplinair en organisatie-overstijgend samenwerken

Het is een intensieve periode geweest waarin we het de studenten, en hun afstudeerbegeleiders, niet altijd makkelijk hebben gemaakt. Het project stelde namelijk bloot hoe de afstudeertrajecten en -eisen verschillen per studie en faculteit binnen de HvA. De studenten en docenten gingen hier uiteindelijk soepel mee om, maar dit was zeker wennen voor ze tijdens de start van de afstudeerkring. Ook voor de opdrachtgevers en begeleiders was het een leerproces waarin we samen in een iteratief proces onze werkwijze en opdrachten moesten aanpassen.

Bij veel van de vraagstukken die langskomen in het Amsterdam Smart City netwerk gaat het over het belang van domein overstijgend werken en hoe veel moeite grote (overheids)organisaties hier mee hebben. Juist daarom kijken we tevreden en trots terug op dit proces. Op deze manier hebben we de studenten voor de start van hun carrière al laten kennismaken met het samenwerken op maatschappelijke vraagstukken, met anderen, die vanuit hun eigen expertise, achtergrond en creativiteit naar problemen en oplossingen kijken.

Hogeschool van Amsterdam is op zoek naar een nieuw vraagstuk!

Ook komend jaar (start 2025) gaan we weer met veel enthousiasme aan de slag met een vraagstuk voor een nieuwe lichting afstudeerders. Om het onderwerp verder te brengen en om samen nog meer te leren over interdisciplinair samenwerken aan maatschappelijke vraagstukken. Samen met de HvA zijn we daarom op zoek naar een nieuw maatschappelijk vraagstuk voor de volgende groep afstudeerders. We zijn op zoek naar een onderwerp, maar ook een organisatie die, in combinatie met een ASC collega, als mede-opdrachtgever en begeleider zal optreden. Dit kan uiteraard in samenwerking met andere ASC partners.

Het onderwerp zal eind september bekend moeten zijn. In de weken die daarop volgen, zal de (groeps)opdracht gefinetuned worden en start de werving van geschikte studenten die in 2025 afstuderen.

Voor meer informatie kun je contact opnemen met Marije Poel (m.h.poel@hva.nl), Nora Rodenburg (n.m.rodenburg@hva.nl) of mij (pelle@amsterdamsmartcity.com)

________________________________________

ENGLISH:

During the first half of 2024, we collaborated with four students from the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences (HvA) on the theme of Mobility Justice. Together with the Province of North Holland, we had the privilege of being part of a pioneering project: the first interdisciplinary graduation circle at the HvA. The graduates came from different programmes, and the group of four included two Public Administration students (Jade Salomons and Timo van Elst), a student Applied Psychology (Jackie Ippel), and a Communication and Multimedia Design student (Merel Thuis).

The HvA aims to familiarise its students early on with interdisciplinary collaboration and research. A complex, cross-domain issue like Mobility Justice, which has been a topic of focus within the Amsterdam Smart City network for some time (LINK), proved to be an excellent subject for their first graduation circle. For both the HvA and the commissioners of the topic, this project was new and presented many uncertainties, but driven by our value of ‘learning by doing,’ we embarked on this journey together!

Results

Following a kick-off with members of the Mobility Justice working group and exploratory interviews with specialists from the Province of North Holland, the students began to formulate concrete research questions. After a broad introduction and question formulation, each student chose a specific sub-topic to focus on for their graduation project. Below, I briefly outline the different topics and results. For further questions, feel free to contact me or Bas Gerbrandy (PNH, bas.gerbrandy@noord-holland.nl).

- Timo looked at the bigger picture, studying how mobility policy is currently structured in North Holland, particularly concerning Mobility Poverty. He also examined the role of participation methods in this context. In his advisory report, he advocates, for example, the installation of participation experts per domain/sector, rather than considering it as a separate team.

- Jackie delved deeper into how civil servants relate to the target group that may experience mobility poverty. She investigated the willingness of civil servants to engage in dialogue with this group, an essential aspect that many still find daunting. Jackie also assisted with Jade's focus group and qualitative research.

- Jade took to the field, speaking with the elderly in Purmerend about their travel experiences and the barriers they face. Her research highlighted the importance of this issue. For instance, she found that while transport services for the elderly are well-organised, they often feel anxious during their journeys. Poor pavement conditions and the sudden acceleration of buses were frequent topics of concern.

- Finally, Merel worked on a multi-device design. She created a tool that can be used to gather personal experiences from residents. This tool then makes the policy risks and opportunities for the Mobility sector in the province more visible and tangible. It serves as a discussion tool and a bridge between the personal experiences of residents and the more abstract, strategic level of policy officers.

Interdisciplinary and Cross-Organisational Collaboration

It has been an intensive period in which we didn’t always make it easy for the students and their graduation supervisors. The project revealed how graduation trajectories and requirements vary across programmes and faculties within the HvA. The students and lecturers eventually handled this smoothly, but it was certainly an adjustment for them at the start of the graduation circle. It was also a learning process for the supervisors, where we had to iteratively adapt our working methods and assignments together.

Many of the issues that arise in the Amsterdam Smart City network relate to the importance of cross-domain collaboration and the difficulties that large (government) organisations often face with this. That’s why we look back on this process with satisfaction and pride. We have introduced the students to the practice of working on social issues, with others who bring their own expertise, background, and creativity to the table, before the start of their careers.

Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences is Looking for a New Topic!

Next year (start of 2025), we will again enthusiastically tackle a new topic with a fresh group of graduates, to further advance the subject and learn even more about interdisciplinary collaboration on social issues. Together with the HvA, we are therefore looking for a new social issue for the next group of graduates. We are searching for a topic, as well as an organisation that, in combination with an ASC colleague, will act as a co-client and supervisor. This can, of course, be in collaboration with other ASC partners.

The topic should be finalised by the end of September. In the weeks after, the (group) assignment will be fine-tuned, and the recruitment of suitable students graduating in 2025 will begin.

For more information, you can contact Marije Poel (m.h.poel@hva.nl), Nora Rodenburg (n.m.rodenburg@hva.nl), or me (pelle@amsterdamsmartcity.com).

Demoday #24: Exploring the public transport of the future with Amsterdam’s Mobility Radar (2024)

Yuki Tol and Joaquim Moody, trend watchers for Smart Mobility at the Innovation Department of the Municipality of Amsterdam, delivered the Mobility Radar on future public Transport.Twee 'moonshots' geven je een,van zo'n 11 jaar) this March. In this first edition, the Amsterdam Smart Mobility program delves deeper into the city's mobility challenges. Will staff and funding shortages, the energy transition, and a growing demand for (accessible) transport options continue to impact the city's future public Transport system? Two 'moonshots' give us a glimpse into the future, showing what public Transport might look like in 2050.

The new concession for public Transport in Amsterdam is nearly ready and will commence in 2025 for a period of approximately 11 years. This is a good time to engage in discussions about the steps that need to be taken to achieve the goals and ambitions set for 2050. It is also crucial to determine what measures are necessary to address the developments that public Transport will face in the future. If the current system is continued, we are only one or two concessions away from 2050. Therefore, now is the time to start working on developments, innovations, and concepts that we want to include in the concessions for the 2030s and 2040s.

Exploring the future together

The Radar team has developed a workshop to engage with various organizations, experts, residents, and enthusiasts to discuss the Mobility Radar. In this workshop, participants jointly explore the trends and developments that can influence the future of mobility. It is a great way for participants to practice this way of thinking, and such a session also brings up topics and discussion points that the Municipality of Amsterdam can incorporate into its future explorations and concessions.

During our 24th Knowledge and Demo Day, Joaquim Moody hosted a work session for a diverse group of participants various organizations and domains. In three groups, we analysed an emerging public Transport challenge using the Mobility Radar approach and creatively thought about solutions. In the following paragraphs, I summarize what we discussed with the group.

Method

The starting point is a number of current challenges in public Transport: staff shortages, funding shortages, accessibility, the energy transition, and the growing demand for public Transport.

Each group selects one of the challenges and then 'dissects' it. Using a worksheet, you look at the following topics: What basic need underlies this challenge? What are examples of how or where you see this challenge currently? What macro changes play a role in the emergence of this challenge – in the long and short term? And how do these macro changes affect which basic needs are important and how they are fulfilled?

Next, you start creating a solution for this challenge and trend. Examples of solutions are: a service, a product, a regulatory adjustment, or an informative campaign. You also need to consider how you would deploy it and who exactly the target audience is.

Results

Accessibility

One of the groups analysed the challenge of public transport accessibility. This needs to be adequate for everyone, now and in the future. Accessibility involves affordability, the digital skills required, travel costs, and physical accessibility. This challenge mainly revolves around the basic needs of connectedness, independence, and control. The macro changes playing a role are migration (increasing number of people to be transported) and aging (more people wanting to travel independently but requiring extra assistance – particularly in digital and physical aspects). Therefore, more space and special assistance will be needed for a growing group of travellers.

The group proposed focusing more on 'micro public transport' and 'on-demand public transport' and making bus and train compartments more flexible. This would make people less dependent on a rigid system and travel environment. The group argued that air travel can serve as an example, where you can specify exactly where you want to sit, whether you need extra space, and if you require extra assistance. These needs deserve more attention in public transport as well. This can be tested with prototypes in train cars and buses and is intended for the target groups: the elderly, people with disabilities, and parents with young children.

Staff Shortages in Public transport

The challenge of 'staff shortages in public transport' is reflected in developments such as cancelled schedules, high work pressure, high absenteeism, strikes, and less social control in public transport (due to less staff). The basic needs affected by this challenge are the need for social status, financial security (for the driver), and a pleasant, healthy workplace. Macro changes playing a role include the large number of job opportunities in other sectors, increasing aggression and hardening in society, worsening public perception of public transport, and aging. As a result, working in public transport has become less prestigious, less safe, relatively less well-paid, and there is little influx of new, young employees.

The group proposed a campaign to improve the image of working in public transport. Currently, too few people choose this profession. However, with campaigns similar to those by the Defense Department, it could be made trendy and attractive again. Influencers or famous Dutch people could also play a role in this. The target audience to be enthused includes young starters and people considering a career switch.

The Growing Demand for public transport

Finally, the third group presented their worksheet regarding the challenge of the growing demand for public transport (and the decline in public transport investments). This is reflected in the decline in service quality, travel options, and the fact that less equipment is available. This affects the basic needs of comfort, connection, and being able to be oneself). Macro changes exacerbating these challenges include the decreasing space for mobility, individualization as a societal development, and increasing travel costs. This leads to a kind of public transport anxiety, aversion, and aggression, which is already happening and is only getting worse, the group noted.

The group proposed recognizing the societal role of public transport more, which would lead to more respect and funding. We should also further 'de-peak' travel times by better aligning telecommuting days or departure times for employees. This can be tested with pilots in specific (travel) areas or with large employers. The target audience can be seen as all travellers together.

Follow-Up

Joaquim will use the presented analyses and solutions as inspiration for further research and use the feedback on the method and workshop to improve such sessions in the future. Enthusiastic participants also wanted to use this method for sessions with students and international delegations, illustrating its success!

During the upcoming Knowledge- and Demo Day, we will have another session on mobility with a similar approach, but this time we will work with the scenario studies made by the Province of North Holland. Thinking about the future using trends, scenarios, and moonshots is essential in every domain, especially when done with a diverse group and maintaining connection.

Public Mobility: an integrated vision on how public transport and shared mobility should work in Noord-Holland

News from the Province Noord-Holland, the Netherlands

Mobility is a necessity for everybody, to be able to work, shop, recreate, visit friends and family, etc. For those who cannot or do not want to use their own means of transport, the province Noord-Holland recemtly adopted a new vision on Public Mobility. This vision aims to make better and affordable public transport possible, also in small towns. How? By making it easier to switch between different modalities. And by offering sustainable, inclusive mobility without using your own means of transport. This includes trains, buses and local buses, but also shared bicycles and shared cars. The province wants public mobility to be well organized everywhere in the province. This is not about more public transport, but about better public transport. It is important that the entire (chain) journey from door to door works well, including:

the train, pre- and post-transport, shared mobility and regional public transport of the Transport Region and surrounding provinces.

Discover here how this system contributes to accessible and future-proof mobility for everyone: 👉https://lnkd.in/e6NeumeZ

Or watch the animation: 👉https://lnkd.in/eTWv3kXw

Citizen's preferences and the 15-minutes city

For decades, the behaviour of urban planners and politicians, but also of residents, has been determined by images of the ideal living environment, especially for those who can afford it. The single-family home, a private garden and the car in front of the door were more prominent parts of those images than living in an inclusive and complete neighbourhood. Nevertheless, such a neighbourhood, including a 'house from the 30s', is still sought after. Attempts to revive the idea of 'trese 'traditional' neighbourhoods' have been made in several places in the Netherlands by architects inspired by the principles of 'new urbanism' (see photo collage above). In these neighbourhoods, adding a variety of functions was and is one of the starting points. But whether residents of such a neighbourhood will indeed behave more 'locally' and leave their cars at home more often does not depend on a planning concept, but on long-term behavioural change.

An important question is what changes in the living environment residents themselves prefer. Principles for the (re)design of space that are in line with this have the greatest chance of being put into practice. It would be good to take stock of these preferences, confront (future) residents conflicting ideas en preconditions, for instance with regard to the necessary density. Below is a number of options, in line with commonly expressed preferences.

1. Playing space for children

Especially parents with children want more playing space for their children. For the youngest children directly near the house, for older children on larger playgrounds. A desire that is in easy reach in new neighbourhoods, but more difficult in older ones that are already full of cars. Some parents have long been happy with the possibility of occasionally turning a street into a play street. A careful inventory often reveals the existence of surprisingly many unused spaces. Furthermore, some widening of the pavements is almost always necessary, even if it costs parking space.

2. Safety

High on the agenda of many parents are pedestrian and cycle paths that cross car routes unevenly. Such connections substantially widen children's radius. In existing neighbourhoods, this too remains daydreaming. What can be done here is to reduce the speed of traffic, ban through traffic and make cars 'guests' in the remaining streets.

3. Green

A green-blue infrastructure, penetrating deep into the immediate surroundings is not only desired by almost everyone, but also has many health benefits. The presence of (safe) water buffering (wadis and overflow ponds) extends children's play opportunities, but does take up space. In old housing estates, not much more is possible in this area than façade gardens on (widened) pavements and vegetation against walls.

4. Limiting space for cars

Even in older neighbourhoods, opportunities to play safely and to create more green space are increased by closing (parts of) streets to cars. A pain point for some residents. One option for this is to make the middle part of a street car-free and design it as an attractive green residential area with play opportunities for children of different age groups. In new housing estates, much more is possible and it hurts to see how conventionally and car-centred these are often still laid out. (Paid) parking at the edge of the neighbourhood helps create a level playing field for car and public transport use.

5. Public space and (shopping) facilities

Sometimes it is possible to turn an intersection, where for instance a café or one or more shops are already located, into a cosy little square. Neighbourhood shops tend to struggle. Many people are used to taking the car to a supermarket once a week to stock up on daily necessities for the whole week. However, some neighbourhoods are big enough for a supermarket. In some cities, where car ownership is no longer taken for granted, a viable range of shops can develop in such a square and along adjacent streets. Greater density also contributes to this.

6. Mix of people and functions

A diverse range of housing types and forms is appreciated. Mixing residential and commercial properties can also contribute to the liveliness of a neighbourhood. For new housing estates, this is increasingly becoming a starting point. For business properties, accessibility remains an important precondition.

7. Public transport

The desirability of good public transport is widely supported, but in practice many people still often choose the car, even if there are good connections. Good public transport benefits from the ease and speed with which other parts of the city can be reached. This usually requires more than one line. Free bus and tram lanes are an absolute prerequisite. In the (distant) future, autonomous shuttles could significantly lower the threshold for using public transport. Company car plus free petrol is the worst way to encourage sensible car use.

8. Centres in plural

The presence of a city centre is less important for a medium-sized city, say the size of a 15-minute cycle zone, than the presence of a few smaller centres, each with its own charm, close to where people live. These can be neighbourhood (shopping) centres, where you are sure to meet acquaintances. Some of these will also attract residents from other neighbourhoods, who walk or cycle to enjoy the wider range of amenities. The presence of attractive alternatives to the 'traditional' city centre will greatly reduce the need to travel long distances.

The above measures are not a roadmap for the development of a 15-minute city; rather, they are conditions for the growth of a liveable city in general. In practice, its characteristics certainly correspond to what proponents envisage with a 15-minute city. The man behind the transformation of Paris into a 15-minute city, Carlos Moreno, has formulated a series of pointers based on all the practical examples to date, which can help citizens and administrators realise the merits of the 15-minute city in their own environments. This book will be available from mid-June 2024 and can be reserved HERE.

For now, this is the last of the hundreds of posts on education, organisation and environment I have published over the past decade. If I report again, it will be in response to special events and circumstances and developments, which I will certainly continue to follow. Meanwhile, I have started a new series of posts on music, an old love of mine. Check out the 'Expedition music' website at hermanvandenbosch.online. Versions in English of the posts on this website will be available at hermanvandenbosch.com.

Will the 15-minute city cause the US suburbs to disappear? 6/7

Urbanisation in the US is undergoing major changes. The image of a central city surrounded by sprawling suburbs therefore needs to be updated. The question is what place does the 15-minute city have in it? That is what this somewhat longer post is about

From the 1950s, residents of US cities began moving en masse to the suburbs. A detached house in the green came within reach for the middle and upper classes, and the car made it possible to commute daily to factories and offices. These were initially still located in and around the cities. The government stimulated this development by investing billions in the road network.

From the 1980s, offices also started to move away from the big cities. They moved to attractive locations, often near motorway junctions. Sometimes large shopping and entertainment centres also settled there, and flats were built on a small scale for supporting staff. Garreau called such cities 'edge cities'.

Investors built new suburbs called 'urban villages' in the vicinity of the new office locations, significantly reducing the distance to the offices. This did not reduce congestion on congested highways.

However, more and more younger workers had no desire to live in suburbs. The progressive board of Arlington, near Washington DC, took the decision in the 1980s to develop a total of seven walkable, inclusive, attractive and densely built-up cores in circles of up to 800 metres around metro stations. In each was a wide range of employment, flats, shops and other amenities . In the process, the Rosslyn-Balston Corridor emerged and experienced rapid growth. The population of the seven cores now stands at 71,000 out of a total of 136,000 jobs. 36% of all residents use the metro or bus for commuting, which is unprecedentedly high for the US. The Rosslyn-Balston Corridor is a model for many other medium-sized cities in the US, such as New Rochelle near new York.

Moreover, to meet the desire to live within walking distance of all daily amenities, there is a strong movement to also regenerate the suburbs themselves. This is done by building new centres in the suburbs and densifying part of the suburbs.

The new centres have a wide range of flats, shopping facilities, restaurants and entertainment centres. Dublin Bridge Park, 30 minutes from Columbus (Ohio) is one of many examples.

It is a walkable residential and commercial area and an easily accessible centre for residents from the surrounding suburbs. It is located on the site of a former mall.

Densification of the suburbs is necessary because of the high demand for (affordable) housing, but also to create sufficient support for the new centres.

Space is plentiful. In the suburbs, there are thousands of (semi-)detached houses that are too large for the mostly older couples who occupy them. An obvious solution is to split the houses, make them energy-positive and turn them into two or three starter homes. There are many examples how this can be done in a way that does not affect the identity of the suburbs (image).

New construction in suburbs

This kind of solution is difficult to realise because the municipal authorities concerned are bound by decades-old zoning plans, which prescribe in detail what can be built somewhere. Some of the residents fiercely oppose changing the laws. Especially in California, the NIMBYs (not in my backyard) and the YIMBYs (yes in my backyard) have a stranglehold on each other and housing construction is completely stalled.

But even without changing zoning laws, there are incremental changes. Here and there, for instance, garages, usually intended for two or three cars, are being converted into 'assessor flats' for grandma and grandpa or for children who cannot buy a house of their own. But garden houses are also being added and souterrains constructed. Along the path of gradualness, this adds thousands of housing units, without causing much fuss.

It is also worth noting that small, sometimes sleepy towns seem to be at the beginning of a period of boom. They are particularly popular with millennials. These towns are eminently 'walkable' , the houses are not expensive and there is a wide range of amenities. The distance to the city is long, but you can work well from home and that is increasingly the pattern. The pandemic and the homeworking it has initiated has greatly increased the popularity of this kind of residential location.

All in all, urbanisation in the US can be typified by the creation of giant metropolitan areas, across old municipal boundaries. These areas are a conglomeration of new cities, rivalling the old mostly shrinking and poverty-stricken cities in terms of amenities, and where much of employment is in offices and laboratories. In between are the suburbs, with a growing variety of housing. The aim is to create higher densities around railway stations. Besides the older suburbs, 'urban villages' have emerged in attractive locations. More and more suburbs are getting their own walkable centres, with a wide range of flats and facilities. Green space has been severely restricted by these developments.

According to Christopher Leinberger, professor of real estate and urban analysis at George Washington University, there is no doubt that in the US, walkable, attractive cores with a mixed population and a varied housing supply following the example of the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor are the future. In addition, walkable car-free neighbourhoods, with attractive housing and ample amenities are in high demand in the US. Some of the 'urban villages' are developing as such. The objection is that these are 'walkable islands', rising in an environment that is anything but walkable. So residents always have one or two cars in the car park for when they leave the neighbourhood, as good metro or train connections are scarce. Nor are these kinds of neighbourhoods paragons of a mixed population; rents tend to be well above the already unaffordable average.

The answer of the question in the header therefore is: locally and slowly

Join AMS Institute's Scientific Conference, hosted by TU Delft, Wageningen University & Research, MIT and the City of Amsterdam.

Do you want to learn from and network with the best researchers and scientists working to tackle pressing urban challenges?

AMS Institute, is organizing the AMS Scientific Conference from April 23-25 at the Marineterrein, Amsterdam, to address pressing urban challenges. The event is organized in collaboration with the City of Amsterdam.

The conference brings together leading institutions in urban research and innovation, thought leaders, municipalities, researchers, and practitioners to explore innovative solutions for sustainable development in Amsterdam and other global cities.

Keynotes, research workshops, learning tracks, and special sessions will explore the latest papers in the fields of mobility, circularity, energy transition, climate adaptation, urban food systems, digitization, diversity, inclusion, living labs experimentation, and transdisciplinary research.

Attendees can expect to gain valuable insights into cutting-edge research and engage in meaningful discussions with leading experts in their field. You can see the full program and all available sessions here.

This year's theme is 'Blueprints for messy cities? Navigating the interplay of order and messiness'.

The program

Day 1: The good, the bad, and the ugly

Keynotes by Paul Behrens of Leiden University and Elin Andersdotter Fabre of UN-Habitat will be followed by a city panel including climate activist <strong>Hannah Prins</strong>. The first day concludes with a dinner at the Koepelkerk in Amsterdam: you're welcome to join our three-course meal with a 50 euro ticket.

Day 2️: Amazing discoveries

Keynotes by Carlo Ratti of MIT and Sacha Stolp of the Municipality of Amsterdam discuss innovation and research in cities. <strong>Corinne Vigreux</strong>, co-founder of TomTom, and Erik Versnel from Rabobank will participate in the city panel.

Day 3️: We are the city

Keynotes by Paul Chatterton of Leeds University and Victor Neequaye Kotey Deputy Director of the Waste Management Department of the Accra Metropolitan Assembly, Ghana. They discuss how we shape the future of our cities together. This will be followed by a city panel including Ria Braaf-Fränkel of WomenMakeTheCity and prof. dr. Aleid Brouwer of the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen.

To buy tickets: You can secure your conference tickets through our website.

Dinner tickets: On April 23 we’re hosting a dinner at the Koepelkerk in Amsterdam. Tickets for this can be added to your conference pass or bought separately.

How do higher density and better quality of life go together? 3/7

A certain degree of compactness is essential for the viability of 15-minute cities. This is due to the need for an economic threshold for facilities accessible by walking or cycling. A summary of 300 research projects by the OECD shows that compactness increases the efficiency of public services in all respects. But it also reveals disadvantages in terms of health and well-being due to pollution, traffic, and noise. The assumption is that there is an optimal density at which both pleasant living and the presence of everyday facilities - including schools - can be realised. At this point, 'densification' is not at the expense of quality of life but contributes to it. A lower density results in more car use and a higher density will reduce living and green space and the opportunity to create jobs.

The image above is a sketch of the 'Plan Papenvest' in Brussels. The density, 300 dwellings on an area of 1.13 hectares, is ten times that of an average neighbourhood. Urban planners often mention that the density of Dutch cities is much lower than in Paris and Barcelona, for example. Yet it is precisely in these cities that traffic is one of the main causes of air pollution, stress, and health problems. The benefits of compactness combined with a high quality of life can only be realised if the nuisances associated with increasing density are limited. This uncompromisingly means limiting car ownership and use.

Urban planners often seem to argue the other way round. They argue that building in the green areas around cities must be prevented at all costs to protect nature and that there is still enough space for building in the cities. The validity of this view is limited. In the first place, the scarce open space within cities can be better used for clean workshops and nature development in combination with water control. Secondly, much of the 'green' space outside cities is not valuable nature at all. Most of it is used to produce feed for livestock, especially cows. Using a few per cent of this space for housing does not harm nature at all. This housing must be concentrated near public transport. The worst idea is to add a road to the outskirts of every town and village. This will undoubtedly increase the use of cars.

Below you can link to my free downloadable e-book: 25 Building blocks to create better streets, neighborhoods and cities

The 15-minute city: from metaphor to planning concept (2/7)

Carlos Moreno, a professor at the Sorbonne University, helped Mayor Anne Hidalgo develop the idea of the 15-minute city. He said that six things made people happy: living, working, amenities, education, wellbeing, and recreation. The quality of the urban environment is enhanced when these functions are realized near each other. The monofunctional expansion of cities in the US, but also in the bidonvilles of Paris, is a thorn in his side, partly because this justifies owning a car.

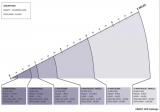

A more precise definition of the concept of the 15-minute city is needed before it can be implemented on a large scale. It is important to clarify which means of transport must be available to reach certain facilities in a given number of minutes. The list of facilities is usually very comprehensive, while the list of means of transport is usually only vaguely defined. But the distance you can travel in 15 minutes depends on the availability of certain modes of transport (see figure above).

Advocates of "new urbanism" have developed the tools to design 15-minute cities. They are based on three zones: the 5-minute walking zone, the 15-minute walking zone, which coincides with the 5-minute cycling zone, and finally the 15-minute cycling zone. These are not static concepts: In practice, the zones overlap and complement each other.

The 5-minute walking zone

This zone corresponds to the way in which most residential neighbourhoods functioned up until the 1960s, wherever you are in the world. Imagine a space with an average distance from the center to the edge of about 400 meters. In the center you will find a limited number of shops, a (small) supermarket, one or more cafes and a restaurant. The number of residents will vary between two and three thousand. Density will decrease from the centre and the main streets outwards. Green spaces, including a small neighbourhood park, will be distributed throughout the neighbourhood, as will workshops and offices.

In the case of new construction, it is essential that pedestrian areas have a dense network of paths without crossings at ground level with streets where car traffic is allowed. Some paths are wider and allow cycling within the 5- and 15-minute cycle zones. The streets provide access to concentrated parking facilities.

The 5-minute cycle zone and the 15-minute walking zone.

Here the distance from the center to the edge is about one kilometer. In this area, most of the facilities that residents need is available and can be distributed around the centers of the 5-minute walking zones. For example, a slightly larger supermarket may be located between two 5-minute walking zones. This zone will also contain one or more larger parks and some larger concentrations of employment.

This zone can be a large district of a city, but it can also be a small municipality or district of around 15 to 25,000 inhabitants. With such a population there will be little room for dogmatic design, especially when it comes to existing buildings. But even then, it is possible to separate traffic types by keeping cars off many streets and clustering car parks. The bottom line is that all destinations in this zone can be reached quickly by walking and cycling, and that car routes can be crossed safely.

The car will be used (occasionally) for several destinations. For example, for large shopping trips to the supermarket.

The 15-minute cycle zone.

This zone will be home to 100.00 or more residents. The large variation is due to the (accidental) presence of facilities for a larger catchment area, such as an industrial estate, a furniture boulevard or an IKEA, a university or a (regional) hospital. It is certainly not a sum of comparable 5-minute cycle zones. Nevertheless, the aim is to distribute functions over the whole area on as small a scale as possible. In practice, this zone is also crossed by several roads for car traffic. The network of cycle paths provides the most direct links between the 5-minute cycle zones and the wider area.

The main urban development objectives for this zone are good accessibility to urban facilities by public transport from all neighbourhoods, the prohibition of hypermarkets and a certain distribution of central functions throughout the area: Residents should be able to go out and have fun in a few places and not just in a central part of the city.

Below you can link to my free downloadable e-book: 25 Building blocks to create better streets, neighborhoods and cities.

The 15-minute city: from vague memory to future reality (1/7)

Without changing the transport system in which they operate, the advent of autonomous cars will not significantly improve the quality of life in our cities. This has been discussed in previous contributions. This change includes prioritizing investment in developing high-quality public transport and autonomous minibuses to cover the first and last mile.

However, this is not enough by itself. The need to reduce the distances we travel daily also applies to transporting raw materials and food around the world. This is the subject of a new series of blog posts, and probably the last.

Over the next few weeks I will be discussing the sustainability of the need for people and goods to travel long distances. In many cities, the corona pandemic has been a boost to this idea. Paris is used as an example. But what applies to Paris applies to every city.

When Anne Hidalgo took office as the newly elected mayor in 2016, her first actions were to close the motorway over the Seine quay and build kilometres of cycle paths. Initially, these actions were motivated by environmental concerns. Apparently, there was enough support for these plans to ensure her re-election in 2020. She had understood that measures to limit car traffic would not be enough. That is why she campaigned on the idea of "La Ville du Quart d'Heure", the 15-minute city, also known as the "complete neighbourhood". In essence, the idea is to provide citizens with almost all of their daily needs - employment, housing, amenities, schools, care and recreation - within a 15-minute walk or bike ride of their homes. The idea appealed. The idea of keeping people in their cars was replaced by the more sympathetic, empirical idea of making them redundant.

During pandemics, lockdowns prevent people from leaving their homes or travelling more than one kilometer. For the daily journey to work or school, the tele-works took their place, and the number of (temporary) "pistes á cycler" quickly increased. For many Parisians, the rediscovery of their own neighbourhood was a revelation. They looked up to the parks every day, the neighbourhood shops had more customers, commuters suddenly had much more time and, despite all the worries, the pandemic was in a revival of "village" coziness.

A revival, indeed, because until the 1960s, most of the inhabitants of the countries of Europe, the United States, Canada and Australia did not know that everything they needed on a daily basis was available within walking or cycling distance. It was against this backdrop that the idea of the 15-minute city gained ground in Paris.

We talk about a 15-minute city when neighbourhoods have the following characteristics

- a mix of housing for people of different ages and backgrounds - pedestrians and cyclists

- Pedestrians and cyclists, especially children, can safely use car-free streets.

- Shops within walking distance (up to 400 meters) for all daily needs

- The same goes for a medical center and a primary school.

- There are excellent public transport links;

- Parking is available on the outskirts of the neighbourhood.

- Several businesses and workshops are located in each neighbourhood.

- Neighbourhoods offer different types of meeting places, from parks to cafes and restaurants.

- There are many green and leafy streets in a neighbourhood.

- The population is large enough to support these facilities.

- Citizens have a degree of self-management.

Urban planners have rarely lost sight of these ideas. In many cities, the pandemic has made these vague memories accessible goals, even if they are far from reality.

In the next post, I will reflect on how the idea of the 15-minute city is moving from dream to reality.

Below you can link to my free downloadable e-book: 25 Building blocks to create better streets, neighborhoods and cities

When will robotaxi’s become commonplace? (8/8)

Until recently, optimists would say "in a few years." Nobody believes that anymore, except for Egon Musk. The number of - so far small - incidents involving robot taxis is increasing to such an extent that the cities where these taxis operate on a modest scale, San Francisco in particular, want to take action.

Europe vs USA

In any case, it will take a long time before robotaxis are commonplace in Europe. There are two major differences between the US and Europe when it comes to transportation policy.

In the US, each state can individually determine when autonomous vehicles can hit the road. In Europe, on the other hand, a General Safety Regulation has been in force since June 2022 that applies to all countries. This states, among other things, that a driver must maintain control of the vehicle at all times. Strict conditions apply to vehicles without a driver: separate lanes, short routes on traffic-calmed parts of the public road and always with a 'safety driver' on board.

The second difference is that in the US 45% of all residents do not have public transport available. In Europe you can get almost anywhere by public transport, although the frequency is low in remote areas. Governments say they want to further increase accessibility by public transport, even if this is at the expense of car traffic. To this end, they want an integrated transport policy, a word that is virtually unknown in the US.

Integrated transport policy

In essence, integrated transport policy is the offering of a series of transport options that together result in (1) the most efficient, safe and convenient satisfaction of transport needs, (2) reduction of the need to travel over long distances (including via the '15- minutes city') and (3) minimal adverse effects on the environment and the quality of life, especially in the large cities. In other words, transport is part of policy aimed at improving the quality of the living environment.

Integrated transport policy assesses the role of vehicle automation in terms of their contribution to these objectives. A distinction can be made between the automation of passenger cars (SAE level 1-3) and driverless vehicles (SEA level 4-5).

Automation of passenger cars

Systems such as automatic lane changes, monitoring distance and speed, and monitoring the behavior of other road users are seen as contributing to road safety. However, the driver always remains responsible and must therefore be able to take over steering at any time, even if the car does not emit a (disengagement) signal. Eyes on the road and hands on the wheel.

Driverless cars

'Hail-riding' will result in growth of traffic in cities because the number of car kilometers per user increases significantly, at the expense of walking, cycling, public transport and to a much lesser extent the use of private cars. Sofar, the number of people who switch from their own car to 'hail-riding' is minimal. The only way to reverse this trend is to impose heavy taxes on car kilometers in urban areas. On the other hand, the use of robot shuttles is beneficial in low-traffic areas and on routes from residential areas to a station. Shuttles are also an excellent way to reduce car use locally. For example, in the extensive Terhills resort in Genk, Belgium, where people leave their cars in the parking lot and transfer to autonomous shuttles that connect the various destinations on the site with high frequency.

A few months ago (April 2023), I read that Qbus in the Netherlands wants to experiment with 18-meter-long autonomous buses, for the time being accompanied by a 'safety driver'. Routes on bus lanes outside the busiest parts of the city are being considered. Autonomous metros and trains have been running in various cities, including London, for years. It is this incremental approach that we will need in the coming years instead of dreaming about getting into an autonomous car, where a made bed awaits us and we wakes us rested 1000 kilometers away. Instead of overcrowded roads with moving beds, we are better off with a comfortable and well-functioning European network of fast (sleeper) trains on a more modern rail infrastructure and efficient and convenient pre- and post-transport.

Automated cars; an uncertain future (7/8)

The photograph above is misleading. Reading a book instead of watching the road is not allowed in any country, unless the car is parked.

For more than a decade, car manufacturers have been working on technology to take over driver's actions. A Lot of money has been invested in this short period and many optimistic expectations have been raised, but no large-scale implementation of the higher SAE levels resulted so far. Commercial services with robotaxi’s are scarce and still experimental.

The changing tide

Especially in the period 2015 - 2018, the CEOs of the companies involved cheered about the prospects; soon after, sentiment changed. In November 2018, Waymo CEO John Krafcik said that the spread of autonomous cars is still decades away and that driving under poor circumstances and in overcrowded cities will always require a human driver. Volkswagen's CEO said fully self-driving cars "may never" hit public roads.

The companies involved are therefore increasingly concerned about the return on the $100 billion invested in the development of car automation until the end of 2021. The end of the development process is not yet in sight. Much has been achieved, but the last 20% of the journey to the fully autonomous car will require the most effort and much more investment. Current technology is difficult to perfect. “Creating self-driving robotaxi is harder than putting a man on the moon,” said Jim Farley, CEO of Ford, after terminating Argo, the joint venture with Volkswagen, after the company had invested $100 million in it.

The human brain can assess complex situations on the road much better than any machine. Artificial intelligence is much faster, but its accuracy and adaptability still leave much to be desired. Driverless cars struggle with unpredictability caused by children, pedestrians, cyclists, and other human-driven cars as well as with potholes, detours, worn markings, snow, rain, fog, darkness and so on. This is also the opinion of Gabriel Seiberth, CEO of the German computer company Accenture, and he advises the automotive industry to focus on what is possible. Carlo van de Weijer, director of Artificial Intelligence at TU Eindhoven, agrees: “There will not be a car that completely takes over all our tasks.”

Elon Musk, on the other hand, predicted that by 2020 all Tesla’s will have SEA level 5 thanks to the new Full Self Driving Chip. In 2023 we know that its performance is indeed impressive. Tesla may therefore be the first car to be accredited at SAE level 3. That is not yet SAE level 5. The question is whether Elon Musk minds that much!

The priorities of the automotive industry

For established automotive companies, the priority is to sell as many cars as possible and not to make a driver redundant. The main objective is therefore to achieve SAE levels 2 and possibly 3. The built-in functions such as automatic lane changing, keeping distance, and passing will contribute to the safe use of cars, if drivers learn to use them properly. Research shows that drivers are willing to pay an average of around $2,500 for these amenities. That is different from the $15,000 that the beta version of Tesla's Full Self Driving system costs.

The automotive industry is in a phase of adjusting expectations, temporizing investments, downsizing involved business units, and looking for partnerships. GM and Honda are collaborating on battery development; BMW, Volkswagen and Daimler are in talks to share R&D efforts for autonomous vehicles; and Ford and VW have stopped developing an autonomous car and are working together on more realistic ambitions.

Safety issues at SAE level 3

But even with a focus on SAE level 3, the problems do not go away. The biggest safety problem may well lie at this level. Elon Musk has suggested for years that Tesla's autopilot would allow drivers to read a book or watch a movie. All they must do is stay behind the wheel. They must be able to take control of the car if the automatic system indicates that it can no longer handle the situation. Studies in test environments show that in this case the reaction time of drivers is far too long to prevent disaster. An eye on the road and a hand on the wheel is still mandatory everywhere in the world, except in few paces for cars accredited at SEA level 4 under specified conditions.

The assumption is that the operating system is so accurate that it indicates in time that it considers the situation too complex. But there are still many doubts as to whether these systems themselves are sufficiently capable of properly assessing the situation on the road at all times. Recent research from King's College London showed that pedestrian detection systems are 20% more accurate when dealing with white adults than when dealing with children and 7.5% more accurate when dealing with white people compared to people with dark skin.

In the next post I will go into more detail about the legislation and what the future may bring.

You still can download for free my newest e-book '25 building blocks to create better streets, neighborhoods and cities' by following the link below

First driverless taxis on the road (6/8)

Since mid-2022, Cruise and Waymo have been allowed to offer a ride-hailing service without a safety driver in a quiet part of San Francisco from 11pm to 6am. The permit has now been extended to the entire city throughout the day. The company has 400 cars and Waymo 250. So far, it has not been an unqualified success.

A turbulent start

In a hilarious incident, an empty taxi was pulled over by police; it stopped properly, but kept going after a few seconds, leaving the officers wondering if they should give chase. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is investigating this incident, as well as several others involving Cruise taxis stalling at intersections, and the Fire Department reports 60 incidents involving autonomous taxis.

Pending further investigation, both companies are only allowed to operate half of their fleet. In addition to the fire department and public transport companies, trade unions are also opposed to the growth of autonomous taxis. California's governor has rejected the objections, fearing that BigTech will swap the state for more car-friendly ones. It is expected that autonomous taxis will gradually enter all major US cities, at a rate just below that of Uber and Lyft.

Cruise has already hooked another big fish: In the not-too-distant future, the company will be allowed to operate autonomous taxis in parts of Dubai.

The number of autonomous taxi services in the world can still be counted on one hand. Baidu has been offering ride-hailing services in Wuhan since December 2022, and robot taxis have been operating in parts of Shenzen since then.

Singapore was the first city in the world to have several autonomous taxis operating on a very small scale. These were developed by nuTonomy, an MIT spin-off, but the service is still in an experimental phase. Another company, Mobileye, also plans to start operating in Singapore this year.

The same company announced in 2022 that it would launch a service in Germany in 2023 in partnership with car rental company Sixt 6, but nothing more has been heard. A survey by JD Power found that almost two-thirds of Germans do not trust 'self-driving cars'. But that opinion could change quickly if safety is proven and the benefits become clear.

What is it like to drive a robotaxi?

Currently, the group of robotaxi users is still small, mainly because the range is limited in space and time. The first customers are early adopters who want to experience the ride.

Curious readers: Here you can drive a Tesla equipped with the new beta 1.4 self-driving system, and here you can board a robotaxi in Shenzhen.

The robotaxis work by hailing: You use an app to say where you are and where you want to go, and the computer makes sure the nearest taxi picks you up. Meanwhile, you can adjust the temperature in the car and tune in to your favourite radio station.

Inside the car, passengers will find tablets with information about the journey. They remind passengers to close all doors and fasten their seatbelts. Passengers can communicate with remote support staff at the touch of a button. TV cameras allow passengers to watch. Passengers can end the journey at any time by pressing a button. If a passenger forgets to close the door, the vehicle will do it for them.

The price of a ride in a robotaxi is just below the price of a ride with Uber or Lyft. The price level is strongly influenced by the current high purchase price of a robotaxi, which is about $175,000 more than a regular taxi. Research shows that people are willing to give up their own cars if robotaxis are available on demand and the rides cost significantly less than a regular taxi. But then the road is open for a huge increase in car journeys, CO2 emissions and the cannibalisation of public transport, which I previously called the horror scenario.

Roboshuttles

In some cities, such as Detroit, Austin, Stockholm, Tallinn and Berlin, as well as Amsterdam and Rotterdam, minibuses operate without a driver, but usually with a safety officer on board. They are small vehicles with a maximum speed of 25 km/h, which operate in the traffic lane or on traffic-calmed streets and follow a fixed route. They are usually part of pilot projects exploring the possibilities of this mode of transport as a means of pre- and post-transport.

Free download

Recently, I published a new e-book with 25 advices for improving the quality of our living environment. Follow the link below to download it for free.

4. The automation of driving: two views (4/4)

At this time, every car manufacturer plus hundreds of startups are working on developing artificial intelligence for driving automation. This should enable communication with the car’s passengers, sensing and anticipating the behavior of other vehicles and road users, communicating with the cloud and planning a safe and fast journey. I will write later about the investments made to achieve this goal.

The development of car automation became visible when Google was the first to start a project in 2009. The activities that technology companies and the automotive industry carry out start from two different visions of the desired result.

Maintain the existing traffic system

The first view assumes that automation is a gradual process that will result in drivers ability to transfer control of the vehicle in a safe manner. It is provisionally assumed that a driver will always be present. That is why taking over control is no problem under specific conditions, such as bad weather and crowded streets. Tesla, an outspoken supporter of this vision, has therefore been talking about its autopilot for years. This came under heavy criticism because the number of functions that were automated was limited. Partly because of this, the so-called autopilot could only be used on a limited number of roads and under favorable conditions.

Most established automotive manufacturers primarily have in mind the higher segment of automobiles and announce they will only make relatively cheaper models suitable for this purpose at a later stage. Maintaining the current traffic system is paramount. The car industry wants to avoid at all costs that people will eventually stop buying cars and limit themselves to ride-hailing in autonomous vehicles.

Moving towards another traffic system

The latter is exactly the intention of the companies that adhere to the second vision. These primarily include non-traditional automotive companies, with Google (later Alphabet) in the lead. What they had in mind from the start was to achieve SAE level 4 and, in the long term, SAE 5 level, cars that can drive safely on the road without the presence of a driver. Companies belonging to this group advocate a completely new transport system. In their opinion, safe driving at SAE level 3 is impossible if the driver is not constantly paying attention. They believe that in the event of a 'disengagement signal', taking control of the car takes too much time and will result in dangerous situations. In addition to Google, Uber (in collaboration with Volvo) also belonged to this group, but now appears to have dropped out. This also applies to Ford and Volkswagen. General Motors is betting on two horses and aims to maintain accreditation at SAE level 4 with its subsidiary Cruise, although Alphabet's subsidiary Waymo has by far the best cards.

Important message for the readers

From next year on, the frequency of my articles about the quality of our living environment will decrease. I admit to an old love: Music. In my new website (in Dutch) I write about why we love music, richly provided with examples. Maybe you will like it. Follow the link below to have a look.

Why we should stop talking about self-driving cars (3/8)

The term 'self-driving car' is used for a wide variety of technical support systems for car drivers. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) has distinguished six types, as mentioned in the tabel above. This classification is recognized worldwide.

At SAE level 0, a car has been equipped with various warning systems, such as unvoluntary deviation from lane, traffic in the blind spot, and emergency braking.

At SEA levels 1 and 2, cars can steer independently or/and adjust their speed in specific conditions on motorways. Whether drivers are allowed to take their hands from the steering wheel depends on national law. That is certainly not the case in Europe. As soon as environmental conditions make steering and acceleration more complex, for example after turning onto a busy street, the driver must immediately take over the steering.

A properly functioning SAE Level 3 system allows drivers to take their eyes off the road and focus on other activities. They must sit behind the wheel and be on standby and are always held responsible for driving the car. They must immediately take over control of the car as soon as 'the system' gives a ('disengagement') signal, which means that it can no longer handle the situation. There is currently no car worldwide that is accredited at SEA-3 level.

This level of control is not sufficient for driverless taxi services. Automotive and technology companies such as General Moters and Alphabet have been working hard to meet the requirements of the higher levels (SAE 4). Their expensive cars (up to $250,000) have automated backups, meaning they can handle any situation under specified conditions, such as well-designed roads, during the day and at a certain speed. Under these circumstances, no driver is required to be present.

SAE Level 5 automation can operate without a driver in all conditions. There is currently no vehicle that meets this requirement.

The variety of options in this classification explains why the term 'self-driving car' should not be used. Cars classified at SAE level 1 and 2 can best be called 'automated cars' and cars from SAE level 3 onwards can be called autonomous cars.

The state of California introduced new rules in 2019 that allow cars at SAE 4 level to participate in traffic. Very strict conditions apply to this. As a result, Alphabet (Waymo) and General Motors (Cruise) have been allowed to launch driverless taxi services. All rides are monitored with cameras to prevent reckless behavior or vandalism.

<strong>Last week, you might have read the last in a series of 25 posts about improving environmental quality. Right now, I have finalized an e-book containing all posts plus additional recommendations. If you follow the link below, you can download the book (90 pages) for free. A version in Dutch language can be downloaded HERE**</strong>

My personal highlights and learnings from the World Smart City Expo 2023

At the start of November, I was lucky enough to visit Barcelona for the World Smart City Expo 2023. Together with my Amsterdam Smart City colleagues and a group of our network partners, I organized -and took part in- keynotes, panel discussions, workshops and visits to international pavilions. As this was my second time visiting the Expo with our network, I was able to keep my focus on the content amidst the overwhelming congress hall and side activities. The following text describes some of my best insights and discoveries.

Informal Transport: Challenges and Opportunities