Stay in the know on all smart updates of your favorite topics.

Demoday #27: What is ethical mobile software for your phone?

We depend heavily on Big Tech companies like Google, Meta, Apple, Amazon, and more. And with your smartphone, there is no escaping them. Even if you don’t use social media, and use anti-tracking software, some of your data will still be shared and sold. This can make you feel pretty uncomfortable. Especially, since most of these tech companies are in the USA and China. This is why, in this session, we worked on the question: Is it possible to develop mobile software which is ethical and functional?

Danny Lämmerhirt from Waag Futurelab works on the MOBIFREE project. This project aims to change the development and use of mobile software in Europe by citizens, businesses, non-profits and governments. In doing so, they want to support the emerging movement for ethical mobile software consisting of organisations that adhere to European values such as openness, privacy, digital sovereignty, fairness, collaboration, sustainability, and inclusivity.

In this session, Danny introduced us to the smartphone they are working on. This smartphone has its hardware from Fairphone (an ethically produced smartphone) and uses a privacy-friendly operating system: Murena. This operating system is an Android fork that doesn’t come with standard tracking software. On top of that, it has an app store with only ethical apps and is connected to an ethical European cloud.

Outcomes

We discussed with the group what values we found most important in an ethical mobile phone when using it for work. The values that were deemed most important by the group were:

- Autonomy: A smartphone allows working wherever and whenever you want. It is an incredibly powerful tool that you can use for so many different things, and it fits in your pocket.

- Independency: We’ve become incredibly dependent on our smartphones. When you lose your phone, you no longer have your money, your public transport card, a map to find the way, etc. On the other hand, this also means that you don’t need to travel with a bag full of tools every time you leave the house.

- Privacy: Constantly being tracked has become normal, but that doesn't mean we’re happy with it. Right now, you don’t have a choice. It would be nice to have a choice, to either pay with your data, or with money.

- User-friendliness: An ethical and privacy-friendly smartphone sounds great, but it also means that you can no longer use many of the apps that you’re used to. Will it still be practical to use? And will it be intuitive? We are all used to a certain way of working and are hesitant to change.

This discussion was definitely food for thought. We all want a more ethical phone, but are not willing to sacrifice much in return…

Are you interested in trying out this ethical smartphone? The MOBIFREE project is currently looking for people who can test this smartphone. They are looking for young adults, civil servants, mobile software developers, and professionals working in humanitarian organisations.

<strong>Would you like to participate, or do you have any questions about this project? Please contact Noor at noor@amsterdaminchange.com. Special thanks to Danny Lämmerhirt for this interesting session.</strong>

Smart City Expo World Congress | Barcelona 2024 | Personal highlights

In early November, I travelled to Barcelona for the third time to attend the Smart City Expo World Congress. Together with the Amsterdam InChange Team, some of our network partners, and the Dutch delegation, we put together a strong content-focused programme, gained inspiration, and strengthened both international and national connections. In this article, I’ll briefly share some of my personal highlights from this trip.

International Delegations: Building International Connections and Knowledge Exchange at the Expo

During the congress, I organised several guided visits from the Dutch Pavilion in collaboration with the DMI-Ecosystem. The aim of these visits was to connect the Dutch delegation with international colleagues and facilitate knowledge exchange. At the busy expo, full of companies, cities, regions, and conference stages, it’s really appreciated to join planned meetings on specific themes. It’s also a great chance to meet many international representatives in just a few days, since everyone is in the same place at the same time.

We visited and connected with the pavilions of EIT Urban Mobility, Forum Virium (Helsinki), the European Commission, and Catalonian innovations. Topics such as The Future of Mobility, Digital Twins, and Net Zero Cities were central to the discussions. It was a good opportunity to strengthen existing networks and establish new connections. For myself, for Amsterdam InChange, and for the participants joining the meetings.

A few aspects of the visits particularly stood out to me. At Forum Virium Helsinki we met with Timo Sillander and Jaana Halonen. I was impressed by their work with Digital Twins. They focus not only on the technology itself and the efficiency of urban systems, but also on the social dimensions a digital simulation can play into. Think of; unequal distributions of risks related to climate change and extreme weather conditions.

I also appreciated the efforts of the European Commission. They are working to make it easier to navigate research topics, funding opportunities, and findings related to themes like energy-neutral cities. With their new marketplace, there is more focus on small and medium-sized cities across Europe, helping them to benefit from innovations that are often developed in larger urban areas.

Collaborating Internationally on a Regional Challenge: Zero-Emission Zones and City Logistics

On Tuesday, my colleague Chris and I organised a session on zero-emission city logistics. We brought together representatives from Oslo, Helsinki, Stockholm, Munich, and EIT Urban Mobility, as well as the Dutch municipalities of Haarlemmermeer and Amsterdam.

The session built on connections we made during other events on Sunday and Monday, bringing together an international group of stakeholders interested in this topic. During the discussion, we compared how different cities are approaching zero-emission zones and identified shared challenges, particularly in policymaking and working with logistics companies and local entrepreneurs.

It was interesting to see how this topic lends itself so well to international comparison and exchange. For instance, while Amsterdam will be one of the first to implement a strict ZE zone in the city centre, other cities are already ahead in areas like charging infrastructure and the transition to cargo bikes. The group was eager to keep the discussion going, and we’re already planning a follow-up online meeting to continue learning from one another.

Future-Proof Sports Fields, International Dinners, and Bicycles

Finally, a few other topics worth mentioning: I joined an international session hosted by the City of Amsterdam about future-proof sports fields. It was inspiring to reflect on the value and potential of sports fields for neighbourhoods, as well as their use as testing grounds for sustainable innovations. For me, the session reinforced how important these spaces are for local communities in cities, and sparked a new personal interest in this subject.

I also really enjoyed both our own international changemakers’ dinner and another international dinner hosted by Drees & Sommer (thanks for the invitation!). Bringing together an international network — whether as individuals or in small groups — and mixing them at the table sparked meaningful conversations that felt different from those during the formal congress sessions or workshops.

Lastly, it’s great to see more Superblocks and bicycles in the city every year! Go Barcelona!

𝗛𝗼𝘄 𝗰𝗮𝗻 𝗖𝗦𝗥𝗗 𝗯𝗲 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗹𝗮𝘂𝗻𝗰𝗵𝗽𝗮𝗱 for 𝘆𝗼𝘂𝗿 𝘀𝘂𝘀𝘁𝗮𝗶𝗻𝗮𝗯𝗶𝗹𝗶𝘁𝘆 𝗷𝗼𝘂𝗿𝗻𝗲𝘆?

A systems approach is key.

Climate transition plans that lack a systemic perspective can unintentionally shift risks, disrupt supply chains, harm human rights, or even contribute to biodiversity loss. For example, switching to a low-carbon product that requires three times more land may address your carbon goals, but jeopardize your biodiversity targets.

Without considering these interdependencies, your climate strategy may become inefficient and require reworking as new issues arise.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝘀𝘆𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗺𝗶𝗰 𝘀𝗰𝗲𝗻𝗮𝗿𝗶𝗼👇

By addressing root causes and considering the ripple effects of climate decision-making in other areas, a systems lens ensures your plan goes beyond regulatory box-ticking.

Together, we can co-create effective action plans with your stakeholders and develop customized decision-making frameworks, accounting for material impacts on climate, nature, and people across your operations and value chain.

How? Learn how our Systemic Transition Suite can unlock your business’s full potential ⬇️

#BeyondCompliance #climatetransition #sustainabilityreporting #CSRD #ESG #circulareconomy

Citizen's preferences and the 15-minutes city

For decades, the behaviour of urban planners and politicians, but also of residents, has been determined by images of the ideal living environment, especially for those who can afford it. The single-family home, a private garden and the car in front of the door were more prominent parts of those images than living in an inclusive and complete neighbourhood. Nevertheless, such a neighbourhood, including a 'house from the 30s', is still sought after. Attempts to revive the idea of 'trese 'traditional' neighbourhoods' have been made in several places in the Netherlands by architects inspired by the principles of 'new urbanism' (see photo collage above). In these neighbourhoods, adding a variety of functions was and is one of the starting points. But whether residents of such a neighbourhood will indeed behave more 'locally' and leave their cars at home more often does not depend on a planning concept, but on long-term behavioural change.

An important question is what changes in the living environment residents themselves prefer. Principles for the (re)design of space that are in line with this have the greatest chance of being put into practice. It would be good to take stock of these preferences, confront (future) residents conflicting ideas en preconditions, for instance with regard to the necessary density. Below is a number of options, in line with commonly expressed preferences.

1. Playing space for children

Especially parents with children want more playing space for their children. For the youngest children directly near the house, for older children on larger playgrounds. A desire that is in easy reach in new neighbourhoods, but more difficult in older ones that are already full of cars. Some parents have long been happy with the possibility of occasionally turning a street into a play street. A careful inventory often reveals the existence of surprisingly many unused spaces. Furthermore, some widening of the pavements is almost always necessary, even if it costs parking space.

2. Safety

High on the agenda of many parents are pedestrian and cycle paths that cross car routes unevenly. Such connections substantially widen children's radius. In existing neighbourhoods, this too remains daydreaming. What can be done here is to reduce the speed of traffic, ban through traffic and make cars 'guests' in the remaining streets.

3. Green

A green-blue infrastructure, penetrating deep into the immediate surroundings is not only desired by almost everyone, but also has many health benefits. The presence of (safe) water buffering (wadis and overflow ponds) extends children's play opportunities, but does take up space. In old housing estates, not much more is possible in this area than façade gardens on (widened) pavements and vegetation against walls.

4. Limiting space for cars

Even in older neighbourhoods, opportunities to play safely and to create more green space are increased by closing (parts of) streets to cars. A pain point for some residents. One option for this is to make the middle part of a street car-free and design it as an attractive green residential area with play opportunities for children of different age groups. In new housing estates, much more is possible and it hurts to see how conventionally and car-centred these are often still laid out. (Paid) parking at the edge of the neighbourhood helps create a level playing field for car and public transport use.

5. Public space and (shopping) facilities

Sometimes it is possible to turn an intersection, where for instance a café or one or more shops are already located, into a cosy little square. Neighbourhood shops tend to struggle. Many people are used to taking the car to a supermarket once a week to stock up on daily necessities for the whole week. However, some neighbourhoods are big enough for a supermarket. In some cities, where car ownership is no longer taken for granted, a viable range of shops can develop in such a square and along adjacent streets. Greater density also contributes to this.

6. Mix of people and functions

A diverse range of housing types and forms is appreciated. Mixing residential and commercial properties can also contribute to the liveliness of a neighbourhood. For new housing estates, this is increasingly becoming a starting point. For business properties, accessibility remains an important precondition.

7. Public transport

The desirability of good public transport is widely supported, but in practice many people still often choose the car, even if there are good connections. Good public transport benefits from the ease and speed with which other parts of the city can be reached. This usually requires more than one line. Free bus and tram lanes are an absolute prerequisite. In the (distant) future, autonomous shuttles could significantly lower the threshold for using public transport. Company car plus free petrol is the worst way to encourage sensible car use.

8. Centres in plural

The presence of a city centre is less important for a medium-sized city, say the size of a 15-minute cycle zone, than the presence of a few smaller centres, each with its own charm, close to where people live. These can be neighbourhood (shopping) centres, where you are sure to meet acquaintances. Some of these will also attract residents from other neighbourhoods, who walk or cycle to enjoy the wider range of amenities. The presence of attractive alternatives to the 'traditional' city centre will greatly reduce the need to travel long distances.

The above measures are not a roadmap for the development of a 15-minute city; rather, they are conditions for the growth of a liveable city in general. In practice, its characteristics certainly correspond to what proponents envisage with a 15-minute city. The man behind the transformation of Paris into a 15-minute city, Carlos Moreno, has formulated a series of pointers based on all the practical examples to date, which can help citizens and administrators realise the merits of the 15-minute city in their own environments. This book will be available from mid-June 2024 and can be reserved HERE.

For now, this is the last of the hundreds of posts on education, organisation and environment I have published over the past decade. If I report again, it will be in response to special events and circumstances and developments, which I will certainly continue to follow. Meanwhile, I have started a new series of posts on music, an old love of mine. Check out the 'Expedition music' website at hermanvandenbosch.online. Versions in English of the posts on this website will be available at hermanvandenbosch.com.

Samenwerken aan transitievraagstukken; wat is er nodig? - Opbrengsten van het Amsterdam Smart City partnerdiner 2024

Als Amsterdam Smart City netwerk bijten we ons vast in complexe stedelijke transitievraagstukken. Ze zijn complex omdat doorbraken nodig zijn; van kleine doorbraakjes, tot grotere systeem doorbraken. Denk aan bewegingen rond; organisatie-overstijgend werken, domein-overstijgend werken, en van competitief naar coöperatief. Als netwerk zetten we samenwerkingsprojecten op waarin we gaandeweg ondervinden met wat voor barrières we te maken hebben en wat voor doorbraken er nodig zijn.

Tijdens ons jaarlijkse Partnerdiner op 2 april, hadden we het samen met eindverantwoordelijken van onze partnerorganisaties over de strategische dilemma’s die spelen bij transitievraagstukken. Als gespreksstarters gebruikten we onze lopende onderwerpen van 2024: De coöperatieve metropool, de ondergrond, de circulaire metropool en drijvende wijken. De gesprekken aan tafel gingen echter over wat er aan de basis staat van het werken aan transitievraagstukken. Zo ging het bijvoorbeeld over; het samenwerken aan visies en scenario’s, leiderschap, burgerlijke ongehoorzaamheid en de kracht van coöperaties. In dit artikel bespreek ik beknopt een aantal onderwerpen die onder de aandacht werden gebracht door onze gasten.

Belangen en visie organiseren

Bij een vraagstuk of onderwerp als de ondergrond, gaan we het al snel hebben over de data en de oplossingen. Dat is ‘te makkelijk’. Technisch gaat het allemaal wel kunnen, maar als we daar te snel beginnen met de oplossing lopen we over een aantal jaar weer vast. Het is belangrijk om eerst een stapje terug te doen en een gedeeld belang en gedeelde visie te organiseren.

Hoe je belanghebbenden verzamelt, en de methode om tot een gedeelde visie te komen, dat is wat meer aandacht verdient. Neem het ondergrond vraagstuk als voorbeeld. Op welke schaal organiseer je daarvoor de belanghebbenden? Aan de oppervlakte hebben we Gemeentelijke en Provinciale grenzen, maar in de ondergrond liggen netwerken van kabels en leidingen die op andere schaal zijn geïnstalleerd en hebben we te maken met bodemtypologieën met verschillende behoeften.

Samen voorstellen en voorspellen

Dat waar je naartoe wilt werken, dat moet van iedereen voelen. Het is belangrijk om een setting te creëren van gedeeld eigenaarschap, waarin iedereen zich ook gehoord voelt, en dat je voelt dat de mensen met wie je gaat samenwerken ook voor jouw belangen op zullen komen. Om samen tot een visie te komen, is het belangrijk om te werken aan scenario’s en die samen te doorleven. Je moet het dan niet alleen hebben over waar je heen wilt, maar ook uitwerken wat er gebeurt als je niets doet of als het helemaal verkeerd uitpakt.

De scenario’s zouden op waarden moeten rusten. Het beeld wat bij de scenario’s hoort is veranderlijk, maar de waarden niet. Samen ben je continu in samenspraak over wat de waarden betekenen voor het verhaal dat je creëert.

Leiderschap en een interdisciplinaire werkwijze

Transitievraagstukken en bovenstaande aanpakken verdienen een bepaald soort leiderschap. Zo zou een leidinggevende bijvoorbeeld een veranderlijke en faciliterende houding moeten tonen, en moet hij/zij vanuit waarden werken die inspireren en verbinden. Het zou meer moeten gaan over het faciliteren van doeners, het stimuleren van doelgericht samenwerken in plaats van taakgericht en ruimte bieden voor menszijn en persoonlijke expertises. Met dit laatste wordt verwezen naar een stukje burgerlijke ongehoorzaamheid. Om dingen die we belangrijk vinden in gang te zetten moeten we soms even los kunnen denken van onze organisatiestructuren en functies. We zouden wel wat vaker mogen appelleren aan ons menszijn.

Meer faciliteren en minder hiërarchie helpt ons om beleid en praktijk dichter bij elkaar te brengen, en om van competitief naar meer coöperatief te bewegen. Als je naar de uitvoering gaat mag de kracht verplaatsen naar de uitvoerders. De machtsverschuivingen tussen leidinggevenden en de doeners, met specifieke rollen en expertises, mag in een constante wisselwerking rond gaan.

Ook interdisciplinair samenwerken aan transitievraagstukken zal nog meer moeten worden gestimuleerd, en misschien wel de norm moeten worden. Bij overheden en bestuurders bijvoorbeeld, zijn transitie thema’s verdeeld over domeinen als energie, mobiliteit, etc. maar de vraagstukken zelf zijn domein overstijgend. Als voorwaarde zou je kunnen stellen dat je altijd twee transities aan elkaar moet koppelen. We zouden meer inspirerende voorbeelden moeten laten zien waarbij verschillende domeinen en transities aan elkaar worden gekoppeld, door bijvoorbeeld overheden.

Publiek-privaat-civiel

Publieke, private en civiele partijen zouden nog meer naast elkaar aan tafel mogen, in plaats van tegenover elkaar. Bedrijven kunnen verzuild zijn, of zich zo voelen, en zouden nog meer om zich heen kunnen kijken en samenwerken. Niet alleen met overheden, maar ook met civiele organisaties. Er zijn vaak meer gezamenlijke belangen dan we denken.

In een beweging naar niet-competitief samenwerken kunnen coöperaties een belangrijke factor zijn. Wanneer je meer autoriteit bij coöperaties neerlegt, weet je zeker dat er in de basis voor een wijk, een stad, haar inwoners, een publiek belang wordt gewerkt. Er liggen dan ook veel kansen bij een faciliterende houding vanuit de overheid naar coöperaties toe, en in de samenwerking tussen bedrijven en coöperaties.

Er zijn tijdens dit diner veel onderwerpen aan bod gekomen waar we met het netwerk mee aan de slag kunnen in onze programmering. De input wordt gebruikt voor onze lopende vraagstukken en we gaan de komende tijd in gesprek met partners om te kijken of we van start kunnen met verdiepende sessies of het ontwikkelen van methoden op (enkele van) deze onderwerpen.

<em>Wil je doorpraten over deze onderwerpen, met ons - of een van onze partners? Mailen kan naar pelle@amsterdamsmartcity.com*</em>

The global distribution of the 15-minute city idea 5/7

A previous post made it clear that a 15-minute city ideally consists of a 5-minute walking zone, a 15-minute walking zone, also a 5-minute cycling zone and a the 15-minute cycling zone. These three types of neighbourhoods and districts should be developed in conjunction, with employment accessibility also playing an important role.

In the plans for 15-minute cities in many places around the world, these types of zones intertwine, and often it is not even clear which type of zone is meant. In Paris too, I miss clear choices in this regard.

The city of Melbourne aims to give a local lifestyle a dominant place among all residents. Therefore, everyone should live within at most 10 minutes' walking distance to and from all daily amenities. For this reason, it is referred to as a 20-minute city, whereas in most examples of a 15-minute city, such as Paris, it is only about <strong>the round trip</strong>. The policy in Melbourne has received strong support from the health sector, which highlights the negative effects of traffic and air pollution.

In Vancouver, there is talk of a 5-minute city. The idea is for neighbourhoods to become more distinct parts of the city. Each neighbourhood should have several locally owned shops as well as public facilities such as parks, schools, community centres, childcare and libraries. High on the agenda is the push for greater diversity of residents and housing types. Especially in inner-city neighbourhoods, this is accompanied by high densities and high-rise buildings. Confronting this idea with reality yields a pattern of about 120 such geographical units (see map above).

Many other cities picked up the idea of the 15-minute city. Among them: Barcelona, London, Milan, Ottawa, Detroit and Portland. The organisation of world cities C40 (now consisting of 96 cities) elevated the idea to the main policy goal in the post-Covid period.

All these cities advocate a reversal of mainstream urbanisation policies. In recent decades, many billions have been invested in building roads with the aim of improving accessibility. This means increasing the distance you can travel in a given time. As a result, facilities were scaled up and concentrated in increasingly distant places. This in turn led to increased congestion that negated improvements in accessibility. The response was further expansion of the road network. This phenomenon is known as the 'mobility trap' or the Marchetti constant.

Instead of increasing accessibility, the 15-minute city aims to expand the number of urban functions you can access within a certain amount of time. This includes employment opportunities. The possibility of working from home has reduced the relevance of the distance between home and workplace. In contrast, the importance of a pleasant living environment has increased. A modified version of the 15-minute city, the 'walkable city' then throws high hopes. That, among other things, is the subject of my next post.

The '15-minute principle' also applies to rural areas (4/7)

Due to a long stay in the hospital, I was unable to post my columns. I also cannot guarantee their continuity in the near future, but I will do my best...

In my previous post, I emphasised that urban densification should be coordinated with other claims on space. These are: expanding blue-green infrastructure and the desire to combine living and working. I am also thinking of urban horticulture. It is therefore unlikely that all the necessary housing in the Netherlands - mentioned is a number of one million housing units - can be realised in the existing built-up area. Expansion into rural areas is then inevitable and makes it possible to improve the quality of these rural areas. Densification of the many villages and small towns in our country enable to approach them from the '15-minute principle' as well. Villages should thereby become large enough to support at least a small supermarket, primary school and health centre, but also to accommodate small businesses. A fast and frequent public transport-connection to a city, to other villages and to a railway station in the vicinity is important.

A thorny issue is the quality of nature in the rural area. Unfortunately, it is in bad shape. A considerable part of the rural area consists of grass plots with large-scale agro-industrial use and arable land on which cattle feed is grown. Half of the Netherlands is for cows, which, incidentally, are mostly in stalls. Restoring nature in the area that is predominantly characterised by large-scale livestock farming, is an essential task for the coming decades.

The development of sufficiently dense built-up areas both in cities and villages and the development of new nature around and within those cities and villages is a beckoning prospect. This can be done by applying the idea of 'scheggen' in and around medium-sized and large cities. These are green zones that penetrate deep into the urban area. New residential and work locations can then join the already built-up area, preferably along existing railway lines and (fast) bus connections. These neighbourhoods can be built in their entirety with movement on foot and by bicycle as a starting point. The centre is a small densely built-up central part, where the desired amenities can be found.

In terms of nature development, depending on the possibilities of the soil, I am thinking of the development of forest and heath areas and lush grasslands, combined with extensive livestock farming, small-scale cultivation of agricultural and horticultural products for the benefit of nearby city, water features with a sponge function with partly recreational use, and a network of footpaths and cycle paths. Picture above: nature development and stream restoration (Photo: Bob Luijks)

Below you can link to my free downloadable e-book: 25 Building blocks to create better streets, neighborhoods and cities

New article "Guidelines for a participatory Smart City model to address Amazon’s urban environmental problems"

Dear Amsterdam Smart City Managers and Members,

As a member of your digital platform, I would like to sincerely thank you for the insightful emails and contents you provide to members like myself throughout the year.

I am delighted to share with you my latest published article, "Guidelines for a participatory Smart City model to address Amazon’s urban environmental problems," featured in the December 12, 2023 issue of PeerJ Computer Science.

The article can be fully accessed and cited at:

da Silva JG. 2023. Guidelines for a participatory Smart City model to address Amazon’s urban environmental problems. PeerJ Computer Science 9:e1694 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.1694

I welcome you to read my publication and share it with fellow members who may find the digital solutions for the Amazon region useful. Please let me know if you have any feedback or ideas to advance this work.

Sincerely (敬具)

Prof. Jonas Gomes ( 博士ジョナス・ゴメス)

www.jgsilva.org

UFAM/FT Industrial Engineering Department (Manaus-Amazon-Brazil)

The University of Manchester/MIOIR/SCI/AMBS Research Visitor 2020/2023

Digitale tweeling als gesprekspartner in gebiedsontwikkeling

Zie digitale tweelingen niet als dé oplossing voor maatschappelijke vraagstukken die in gebieden spelen. Data en modellen belichten namelijk slechts een deel van de werkelijkheid. Bij ruimtelijke opgaven, zoals het woningtekort, de energietransitie en natuurherstel, gaat het om het gesprek om te komen tot een gedeelde werkelijkheid. Zorg dat digitalisering hierbij een constructieve rol speelt.

Op de grens van Brabant en Limburg ligt de Peel. Daar komen onder grote tijdsdruk verschillende opgaven samen: transitie van de landbouw, omslag naar hernieuwbare energie inclusief netverzwaringen, woningtekort, verdroging van de Peel en de mogelijke heropening van de vliegbasis Vredepeel. Het maken van die ruimtelijke puzzel vergt samenwerking tussen twintig gemeenten, drie waterschappen, twee provincies, diverse departementen en tal van bedrijven, maatschappelijke organisaties en burgers. Daarnaast vraagt die puzzel een integrale afweging: ingrepen voor de ene opgave kunnen immers vergaande gevolgen hebben voor andere opgaven.

Voor de digitale tweeling is echter geen vraagstuk te complex, schreef Microsoft in een artikel op Ibestuur. Het bedrijf werkt zelfs aan een digitale tweeling van de aarde, met de ambitie om deze beter te besturen voor mens en natuur. Tijdens een conferentie over slimme steden in Barcelona viel de sterke aantrekkingskracht van de digitale tweeling voor beleidsmakers en bestuurders op. ‘Doe mij ook maar zo’n digitale tweeling’ leek de dominante gedachte te zijn. De talrijke pilots en experimenten met digitale tweelingen in het ruimtelijk domein onderstrepen dit.

Hype?

Er lijkt sprake van een ‘hype’: digitale tweelingen als panacee voor gebiedsontwikkeling. Deze ‘hype’ hangt samen met de toenemende hoeveelheid en beschikbaarheid van (real-time) data over onze leefomgeving, zoals lucht-, grond- en waterkwaliteit en energieverbruik. Dit is mede het gevolg van het beter en goedkoper worden van monitoringstechnieken, zoals slimme meters in huis en allerlei soorten sensoren op straat, in drones en satellieten. Daarnaast stimuleert en verplicht de aankomende Omgevingswet het gebruik van data.

Partijen gebruiken verschillende definities voor de digitale tweeling. Doorgaans verwijst de term ‘digitale tweeling’ naar het idee dat een fysieke en virtuele ‘tweeling’ met elkaar in verbinding staan door de uitwisseling van data en informatie. Data over de fysieke wereld voeden de virtuele tweeling en inzichten daaruit kunnen weer worden gebruikt om te interveniëren in de fysieke wereld. Dat helpt bij het maken van allerlei producten – van de bouw van de Boekelose brug tot de BMW fabriek – en het verbeteren van bedrijfsprocessen, zoals het onderhoud en beperking van de CO2-uitstoot van de Airbus.

Hierdoor geïnspireerd, zien veel beleidsmakers en bestuurders de digitale tweeling als een belangrijk middel om besluitvorming – van beleidsvoorbereiding tot implementatie – te verbeteren door de gevolgen van keuzes te simuleren en te visualiseren. In het domein van politiek en bestuur is de digitale tweeling dus meer dan een technologische innovatie; het is een democratische innovatie. Dit roept de vraag op: hoe kan een digitale tweeling de besluitvorming daadwerkelijk verbeteren?

Er bestaat geen eenduidige werkelijkheid

Dat kan door de variëteit en veelzijdigheid van een gebied te erkennen. Een gebied is nooit één monolithische werkelijkheid; er spelen vaak duizend-en-een belangen en processen tegelijk. Toch is zo’n eenduidige werkelijkheid wel precies wat een digitale tweeling suggereert. En daarin schuilt zowel de kracht als het risico van dit instrument. Kracht, omdat het zorgt voor een basis voor een gesprek. En een goed gesprek is de basis voor goede besluitvorming. Risico, omdat zo’n eenduidige werkelijkheid ons kan doen vergeten dat de digitale tweeling selectief is. Hij laat slechts een beperkt aantal variabelen zien. Bovendien, datgene wat subjectief of lastiger meetbaar is, bijvoorbeeld de betekenis van een gebied voor haar inwoners, kunnen we gemakkelijk over het hoofd zien. Terwijl een democratisch proces juist ook voor die zachte waarden aandacht behoort te hebben.

Gesprekspartner

Beschouw een digitale tweeling dus niet als de gedeelde werkelijkheid zelf, maar als gesprekspartner in een breder democratisch proces. Daarbij is ook transparantie van belang over welke data wel aanwezig zijn en welke niet. En over welke modellen gebruikt worden en de aannames die daarbij gemaakt worden. Zo laat de maatschappelijke aandacht voor bijvoorbeeld de stikstofmodellen van het RIVM zien dat data en modellen niet neutraal zijn en ook niet apolitiek, ook al worden ze soms wel zo gepresenteerd. Data, modellen en algoritmes hebben namelijk invloed op hoe we problemen definiëren en begrijpen, wie daarbij betrokken worden en hoe we vervolgens handelen. Of toegepast op besluitvorming: ze bepalen welke maatschappelijke opgaven wel en niet worden opgepakt en hoe en wie wel of niet mee mag praten en beslissen.

Praktijkcases?

Dit artikel is een weergave van een aantal eerste inzichten in een project van het Rathenau Instituut naar de wijze waarop digitale tweelingen kunnen bijdragen aan besluitvorming over gebiedsontwikkeling. Hierin heeft het Rathenau samengewerkt met de Provincie Noord-Holland. Voor het vervolg van dit project is het instituut op zoek naar interessante praktijkcases.

De digitale tweeling als gesprekspartner dus. Hoe doe je dat op een verantwoorde manier? Wie kan hier praktijkcases van laten zien?

Dit artikel is geschreven door Romy Dekker (Rathenau Instituut), Paul Strijp (Provincie Noord-Holland) Allerd Nanninga (Rathenau Instituut) en Rinie van Est (Rathenau Instituut) en gepubliceerd op iBestuur. De auteurs danken Brian de Vogel, Henk Scholten, Arny Plomp, Herman Wilken, Rosemarie Mijlhoff, Jan Bruijn en Martine Verweij voor hun waardevolle inbreng in het project.

Beeld: Shutterstock

24 Participation

This is the 24st episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Its topic is how involving citizens in policy, beyond the elected representatives, will strengthen democracy and enhance the quality of the living environment, as experienced by citizens.

Strengthening local democracy

Democratization is a decision-making process that identifies the will of the people after which government implements the results. Voting once every few years and subsequently letting an unpredictable coalition of parties make and implement policy is the leanest form of democracy. Democracy can be given more substance along two lines: (1) greater involvement of citizens in policy-making and (2) more autonomy in the performance of tasks. The photos above illustrate these lines; they show citizens who at some stage contribute to policy development, citizens who work on its implementation and citizens who celebrate a success.

Citizen Forums

In Swiss, the desire of citizens for greater involvement in political decision-making at all levels is substantiated by referenda. However, they lack the opportunity to exchange views, let alone to discuss them.

In his book Against Elections (2013), the Flemish political scientist David van Reybrouck proposes appointing representatives based on a weighted lottery. There are several examples in the Netherlands. In most cases, the acceptance of the results by the established politicians, in particular the elected representatives of the people, was the biggest hurdle. A committee led by Alex Brenninkmeijer, who has sadly passed away, has expressed a positive opinion about the role of citizen forums in climate policy in some advice to the House of Representatives. Last year, a mini-citizen's forum was held in Amsterdam, also chaired by Alex Brenninkmeijer, on the concrete question of how Amsterdam can accelerate the energy transition.

Autonomy

The ultimate step towards democratization is autonomy: Residents then not only decide, for example, about playgrounds in their neighbourhood, they also ensure that these are provided, sometimes with financial support from the municipality. The right to do so is formally laid down in the 'right to challenge'. For example, a group of residents proves that they can perform a municipal task better and cheaper themselves. This represents a significant step on the participation ladder from participation to co-creation.

Commons

In Italy, this process has boomed. The city of Bologna is a stronghold of urban commons. Citizens become designers, managers, and users of part of municipal tasks. Ranging from creating green areas, converting an empty house into affordable units for students, the elderly or migrants, operating a minibus service, cleaning and maintaining the city walls, redesigning parts of the public space etcetera.

From 2011 on commons can be given a formal status. In cooperation pacts the city council and the parties involved (informal groups, NGOs, schools, companies) lay down agreements about their activities, responsibilities, and power. Hundreds of pacts have been signed since the regulation was adopted. The city makes available what the citizens need - money, materials, housing, advice - and the citizens donate their time and skills.

From executing together to deciding together

The following types of commons can be distinguished:

Collaboration: Citizens perform projects in their living environment, such as the management of a communal (vegetable) garden, the management of tools to be used jointly, a neighborhood party. The social impact of this kind of activities is large.

Taking over (municipal) tasks: Citizens take care of collective facilities, such as a community center or they manage a previously closed swimming pool. In Bologna, residents have set up a music center in an empty factory with financial support from the municipality.

Cooperation: This refers to a (commercial) activity, for example a group of entrepreneurs who revive a street under their own responsibility.

Self-government: The municipality delegates several administrative and management tasks to the residents of a neighborhood after they have drawn up a plan, for example for the maintenance of green areas, taking care of shared facilities, the operation of minibus transport.

<em>Budgetting</em>: In a growing number of cities, citizens jointly develop proposals to spend part of the municipal budget.

The role of the municipality in local initiatives

The success of commons in Italy and elsewhere in the world – think of the Dutch energy cooperatives – is based on people’s desire to perform a task of mutual benefit together, but also on the availability of resources and support.

The way support is organized is an important success factor. The placemaking model, developed in the United Kingdom, can be applied on a large scale. In this model, small independent support teams at neighbourhood level have proven to be necessary and effective.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

23. Governance

This is the 23st episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Its topic is the way how the quality of the living environment benefits from good governance.

In 1339 Ambrogio Lorenzetti completed his famous series of six paintings in the town hall of the Italian city of Siena: The Allegory of Good and Bad Government. The image above refers to the characteristics of governance: Putting the interests of citizens first, renouncing self-interest, helpfulness, and justice. These characteristics still apply.

Rooted in the community

The starting point of urban policy is a long-term vision on the development of the city that is tailored to the needs and wishes of citizens, as they become manifest within and beyond the institutional channels of representative democracy. In policies that are rooted in the community, knowledge, experiences, and actions of those involved are also addressed. Each city has a pool of experts in every field; many are prepared to commit themselves to the future of their hometown.

Participation

Governance goes beyond elections, representative bodies, following proper procedures and enforcing the law. An essential feature is that citizens can trust that the government protects their interests and that their voices are heard. The municipality of Amsterdam has access to a broad range of instruments: co-design, Initiating a referendum, subsiding local initiatives, neighbourhood law, including the 'right to challenge' and neighbourhood budgets. I will deal with participation in the next post.

Two-way communication

Barcelona and Madrid both use technical means to give citizens a voice and to make this voice heard in policy. Barcelona developed the platform Decidem (which means 'We decide' in Catalan) and Madrid made available Decide Madrid ('Madrid decides'). Both platforms provide citizens with information about the policy, allow them to put topics on the policy agenda, start discussions, change policy proposals, and issue voting recommendations for the city council.

Madrid has developed its participatory electronic environment together with CONSUL, a Madrid-based company. CONSUL enables cities to organize citizen participation on the internet. The package is very extensive. The software and its use is free. Consul is in use in 130 cities and organizations in 33 countries and has reached some 90 million citizens worldwide.

City management

Each city offers a range of services and facilities, varying from the fire brigade, police, health services, municipal cleaning services to 'Call and repair' lines, enabling residents to report defects, vandalism, damage, or neglect. Nuisance has many sources: non-functioning bridges, traffic lights, behavior of fellow citizens, young and old, traffic, aircraft noise and neighbours. In many cases, the police are called upon, but they are too often unable or unwilling to intervene because other work is considered more urgent. This is detrimental to citizens' confidence in 'politics' and seriously detracts from the quality of the living environment.

Resilience

Cities encounter disasters and chronic problems that can take decades to resolve. Resilience is needed to cope and includes measures that reduce the consequences of chronic stress (e.g., communal violence) and - if possible - acute shocks (e.g., floods) and eliminate their occurrence through measures 'at the source.'

For an adequate approach to disasters, the fire brigade, police, and ambulances work together and involve citizens. This cooperation must be learned and built up through practice, improvisation and trust and is not created through a hierarchical chain of command.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

16. A pleasant (family) home

This is the 16th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. This post is about one of the most important contributions to the quality of the living environment, a pleasant (family)home.

It is generally assumed that parents with children prefer a single-family home. New construction of this kind of dwelling units in urban areas will be limited due to the scarcity of land. Moreover, there are potentially enough ground-access homes in the Netherlands. Hundreds of thousands have been built in recent decades, while families with children, for whom this type of housing was intended, only use 25% of the available housing stock. In addition, many ground-access homes will become available in the coming years, if the elderly can move on to more suitable housing.

The stacked house of your dreams

It is expected that urban buildings will mainly be built in stacks. Stacked living in higher densities than is currently the case can contribute to the preservation of green space and create economic support for facilities at neighbourhood level. In view of the differing wishes of those who will be using stacked housing, a wide variation of the range is necessary. The main question that arises is what does a stacked house look like that is also attractive for families with children?

Area developer BPD (Bouwfonds Property Development) studied the housing needs of urban families based on desk research, surveys and group discussions with parents and children who already live in the city and formulated guidelines for the design of 'child-friendly' homes based on this.

Another source of ideas for attractive stacked construction was the competition to design the most child-friendly apartment in Rotterdam. The winning design would be realized. An analysis of the entries shows that flexible floor plans stand head and shoulders above other wishes. This wish was mentioned no less than 104×. Other remarkably common wishes are collective outdoor space [68×], each child their own place/play area [55×], bicycle shed [43×], roof garden [40×], vertical street [28×], peace and privacy [27× ], extra storage space [26×], excess [22×] and a spacious entrance [17×].

Flexible layout

One of the most expressed wishes is a flexible layout. Family circumstances change regularly and then residents want to be able to 'translate' to the layout without having to move. That is why a fixed 'wet unit' is often provided and wall and door systems as well as floor coverings are movable. It even happens that non-load-bearing partition walls between apartments can be moved.

Phased transition from public to private space

One of the objections to stacked living is the presence of anonymous spaces, such as galleries, stairwells, storerooms, and elevators. Sometimes children use these as a play area for lack of anything better. To put an end to this kind of no man's land, clusters of 10 – 15 residential units with a shared stairwell are created. This solution appeals to what Oscar Newman calls a defensible space, which mainly concerns social control, surveillance, territoriality, image, management, and sense of ownership. These 'neighborhoods' then form a transition zone between the own apartment, the rest of the building and the outside world, in which the residents feel familiar. Adults indicate that the use of shared cars should also be organized in these types of clusters.

Variation

Once, as the housing market becomes less overburdened, home seekers will have more options. These relate to the nature of the house (ground floor or stacked) and - related thereto - the price, the location (central or more peripheral) and the nature of the apartment itself. But also, on the presence of communal facilities in general and for children in particular.

Many families with children prefer that their neighbors are in the same phase of life and that the children are of a similar age. In addition, they prefer an apartment on the ground floor or lower floors that preferably consists of two floors.

Communal facilities

Communal facilities vary in nature and size. Such facilities contain much more than a stairwell, lift and bicycle storage. This includes washing and drying rooms, hobby rooms, opportunities for indoor and outdoor play, including a football cage on the roof and inner gardens. Houses intended for cohousing will also have a communal lounge area and even a catering facility.

However, the communal facilities lead to a considerable increase in costs. That is why motivated resident groups are looking for other solutions.

Building collectively or cooperatively

The need for new buildings will increasingly be met by cooperative or collective construction. Many municipalities encourage this, but these are complicated processes, the result of which is usually a home that better meets the needs at a relatively low price and where people have got to know the co-residents well in advance.

With cooperative construction, the intended residents own the entire building and rent a housing unit, which also makes this form of housing accessible to lower incomes. With collective building, there is an association of owners, and everyone owns their own apartment.

Indoor and outdoor space for each residential unit

Apartments must have sufficient indoor and outdoor space. The size of the interior space will differ depending on price, location and need and the nature of the shared facilities. If the latter are limited, it is usually assumed that 40 - 60 m2 for a single-person household, 60 - 100 m2 for two persons and 80 - 120 m2 for a three-person household. For each resident more about 15 to 20 m2 extra. Children over 8 have their own space. In addition, more and more requirements are being set for the presence, size, and safety of a balcony, preferably (partly) covered. The smallest children must be able to play there, and the family must be able to use it as a dining area. There must also be some protection against the wind.

Residents of family apartments also want their apartment to have a spacious hall, which can also be used as a play area, plenty of storage space and good sound insulation.

'The Babylon' in Rotterdam

De Babel is the winning entry of the competition mentioned before to design the ideal family-friendly stacked home (see title image). The building contains 24 family homes. All apartments are connected on the outside by stairs and wide galleries. As a result, there are opportunities for meeting and playing on all floors. The building is a kind of box construction that tapers from wide to narrow. The resulting terraces are a combination of communal and private spaces. Due to the stacked design, each house has its own shape and layout. The living areas vary between approximately 80 m2 and 155 m2 and a penthouse of 190 m2. Dimensions and layouts of the houses are flexible. Prices range from €400,000 – €1,145,000 including a parking space (price level 2021).

As promised, the building has now been completed, albeit in a considerably 'skimmed-down' form compared to the 'playful' design (left), no doubt for cost reasons. The enclosed stairs that were originally planned have been replaced by external steel structures that will not please everyone. Anyway, it is an attractive edifice.

14. Liveability

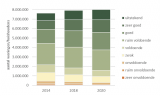

The picture shows the average development of the liveability per household in residential neighborhoods in the Netherlands from 2014 (source: Leefbaarheid in Nederland, 2020)

This is the 14th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. This post discusses how to improve the liveability of neighbourhoods. Liveability is defined as the extent to which the living environment meets the requirements and wishes set by residents.

Differences in liveability between Dutch neighbourhoods

From the image above can be concluded that more than half of all households live in neighborhoods to be qualified as at least 'good'. On the other hand, about 1 million households live in neighborhoods where liveability is weak or even less.

These differences are mainly caused by nuisance, insecurity, and lack of social cohesion. Locally, the quality of the houses stays behind.

The neighborhoods with a weak or poorer liveability are mainly located in the large cities. Besides the fact that many residents are unemployed and have financial problems, there is also a relatively high concentration of (mental) health problems, loneliness, abuse of alcohol and drugs and crime. However, many people with similar problems also live outside these neighbourhoods, spread across the entire city.

Integration through differentiation: limited success

The Netherlands look back on a 75 years period in which urban renewal was high on the agenda of the national and municipal government. Over the years, housing different income groups within each neighbourhood has played a major role in policy. To achieve this goal, part of the housing stock was demolished to be replaced by more expensive houses. This also happened if the structural condition of the houses involved gave no reason to demolishment.

Most studies show that the differentiation of the housing stock has rarely had a positive impact on social cohesion in a neighborhood and often even a negative one. The problems, on the other hand, were spread over a wider area.

Ensuring a liveable existence of the poor

Reinout Kleinhans justly states: <em>Poor neighborhoods are the location of deprivation, but by no means always the cause of it.</em> A twofold focus is therefore required: First and foremost, tackling poverty and a structural improvement of the quality of life of people in disadvantaged positions, and furthermore an integrated neighborhood-oriented approach in places where many disadvantaged people live together.

I have already listed measures to improve the quality of life of disadvantaged groups in an earlier post that dealt with social security. I will therefore focus here on the characteristics of an integrated neighbourhood-oriented approach.

• Strengthening of the remaining social cohesion in neighborhoods by supporting bottom-up initiatives that result in new connections and feed feelings of hope and recognition.

• Improvement of the quality of the housing stock and public space where necessary to stimulate mobility within the neighborhood, instead of attracting 'import' from outside.

• Allowing residents to continue living in their own neighborhood in the event of necessary improvements in the housing stock.

• Abstaining from large-scale demolition to make room for better-off residents from outside the neighborhood if there are sufficient candidates from within.

• In new neighborhoods, strive for social, cultural, and ethnic diversity at neighborhood level so that children and adults can meet each other. On 'block level', being 'among us' can contribute to feeling at home, liveability, and self-confidence.

• Curative approach to nuisance-causing residents and repressive approach to subversive crime through the prominent presence of community police officers who operate right into the capillaries of neighbourhoods, without inciting aggression.

• Offering small-scale assisted living programs to people for whom independent living is still too much of a task. This also applies to housing-first for the homeless.

• Strengthening the possibilities for identification and proudness of inhabitants by establishing top-quality play and park facilities, a multifunctional cultural center with a cross-district function and the choice of beautiful architecture.

• Improving the involvement of residents of neighbourhoods by trusting them and giving them actual say, laid down in neighborhood law.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

9. Road safety

This is the 9th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Casualties in traffic are main threats to the quality of the living environment. ‘Vision zero’ might change this.

Any human activity that annually causes 1.35 million deaths worldwide, more than 20 million serious injuries, damage of $1,600 billion and is a major cause of global warming would be banned immediately. Except for the use of the car. This post describes how changes in road design will improve safety.

The more public transport, the safer the traffic

Researchers from various universities in the US, Australia and Europe have studied the relationship between road pattern, other infrastructure features and road safety or its lack. They compared the road pattern in nearly 1,700 cities around the world with data on the number of accidents, injuries, and fatalities. Lead researcher Jason Thompsonconcluded: <em>It is quite clear that places with more public transport, especially rail, have fewer accidents</em>. Therefore, on roads too public transport must prioritized.

The growing risk of pedestrians and cyclists

Most accidents occur in developing and emerging countries. Road deaths in developed countries are declining. In the US from 55,000 in 1970 to 40,000 in 2017. The main reason is that cars always better protect their passengers. This decrease in fatalities does not apply to collisions between cars and pedestrians and cyclists, many of which are children. Their numbers are increasing significantly, in the US more than in any other developed country. In this country, the number of bicycle lanes has increased, but adjustments to the layout of the rest of the roads and to the speed of motorized traffic have lagged, exposing cyclists to the proximity of speeding or parking cars. SUVs appear to be 'killers'and their number is growing rapidly.

Safe cycling routes

In many American cities, paint is the primary material for the construction of bike lanes. Due to the proximity of car traffic, this type of cycle routes contributes to the increasing number of road deaths rather than increasing safety. The Canadian city of Vancouver, which doubled the number of bicycle lanes in five years to 11.9% of all downtown streets, has the ambition to upgrade 100% of its cycling infrastructure to an AAA level, which means safe and comfortable for all ages and abilities. Cycle paths must technically safe: at least 3 meters wide for two-way traffic; separated from other traffic, which would otherwise have to reduce speed to less than 30 km/h). In addition, users also need to feel safe.

Street design

Vision Zero Cities such as Oslo and Helsinki are committed to reducing road fatalities to zero over the next ten years. They are successful already now: There were no fatalities in either city in 2019. These and other cities use the Vision Zero Street Design Standard, a guide to planning, designing, and building streets that save lives.

Accidents are often the result of fast driving but are facilized by roads that allow and encourage fast driving. Therefore, a Vision Zero design meets three conditions:

• Discouraging speed through design.

• Stimulating walking, cycling and use of public transport.

• Ensure accessibility for all, regardless of age and physical ability (AAA).

The image above shows a street that meets these requirements. Here is an explanation of the numbers: (1) accessible sidewalks, (2) opportunity to rest, (3) protected cycle routes, (4) single lane roads, (5) lanes between road halves, (6) wide sidewalks, (7) public transport facilities, (8) protected pedestrian crossings, (9) loading and unloading bays, (10) adaptive traffic lights.

Enforcement

Strict rules regarding speed limits require compliance and law enforcement and neither are obvious. The Netherlands is a forerunner with respect to the infrastructure for bikes and pedestrians, but with respect to enforcement the country is negligent: on average, a driver of a passenger car is fined once every 20,000 kilometers for a speeding offense (2017 data). In addition, drivers use apps that warn of approaching speed traps. Given the risks of speeding and the frequency with which it happens, this remissing law enforcement approach is unacceptable.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

4. Informative plinths

This article is part of the series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Read how design, starting from street-level view contributes to the quality of the urban environment.

Plinths express the nature of activities inside

The visual quality, design and decoration of the plinth, the 'ground floor' of a building, contributes significantly to the quality of the streetscape and to the (commercial) success of the activities that take place at plinth level. This also applies, for example, if the activities of a workshop can be observed through the windows. Blank walls speed up visitors' pace, unless this wall has attractive art. Vacancy is disastrous.

A plinth displays the destination of a building or a part of it (photo bottom left). Fashion stores and suppliers of delicacies depend on its ability to attract buyers. There is nothing against allowing the plinth to expand slightly onto the street - think of beautiful displays of fresh vegetables - if a sufficiently wide barrier-free pedestrian route is maintained.

The total length of streets that must generate customers and visitors must not be too long in order to keeps vacancy to a minimum. This may mean that still profitable shops in streets where the number of vacancies is increasing must consider moving if revitalization of the street is infeasible. The space left behind can best be revamped into space for housing or offices to prevent further dilapidation.

Plinths of non-commercial destinations

The need for an attractive plinth also applies to non-commercial spaces. This may concern information centers, libraries, day care centers for children or the elderly, places where music groups rehearse, etcetera. Co-housing and co-working centers might also concentrate several activities in a semi-public print. In an apartment building, you might like to see an attractive portal through the glass, with stairs and elevators and a sitting area.

Residential plinths

Houses in the more central parts of the city can also have an attractive plinth. In practice, this happens often by placing plants and creating a seat on the sidewalk. The so-called Delft plinths are narrow, sometimes slightly raised additional sidewalks for plants, a bench, or stalling bicycles (photo bottom middle). The worst is if the plinth of a private house is mainly the garage door.

The aesthetics of the plinth

In many pre-war high streets, the plinth was designed as an integral part of the building. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, many retailers modernized their businesses and demolished entire ground floors. The walls of the upper floor, sometimes of several buildings at the same time, rested on a heavy steel beam and the new plinth was mainly made of glass (photo top left). Often a door to reach the upper floors is missing, complicating the premises’ residential function. Initially, these new fronts increased the attractivity of the ground floor. However, the effect on the streetscape has turned out to be negative. In Heerlen, artist and 'would be' urban planner Michel Huisman (the man behind the Maankwartier) is busy restoring old shopfronts together with volunteers and with the support of the municipality (photos top right). In Amsterdam, shopfronts are also being restored to their original appearance (photo bottom right).

Plinths policy

The sky is the limit for improving plinths, as can be seen in the book Street-Level Architecture, The Past, Present and Future of Interactive Frontages by Conrad Kicker and the *Superplinten Handbook</em> , commissioned by the municipality of Amsterdam.

In 2020, a plinth policy was introduced in the Strijp-S district in Eindhoven from a social-economic background. 20% of the available plinths is destined for starters, pioneers and 'placemakers'. Continuous coordination with the target group is important here. In The Hague, 100 former inner-city shops have now been transformed into workplaces for young and creative companies. Differentiating rents is part of the plinth policy too.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

Transition Day 2023: Digital identity and implementing new electronic identification methods

The Digital Government Act (Wet Digitale Overheid) aims to improve digital government services while ensuring citizens' privacy. An important part of this law is safe and secure logging in to the government using new electronic identification methods (eIDs) such as Yivi (formerly IRMA). The municipality of Amsterdam recently started a pilot with Yivi. Amsterdam residents can now log in to “Mijn Amsterdam” to track the status of complaints about public area’s. But how do you get this innovation, which really requires a different way of thinking, implemented?

Using the Change Curve to categorise barriers

At the Transition day (June 2023), Mike Alders (municipality of Amsterdam) invited the Amsterdam Smart City network to help identify the barriers and possible interventions, and explore opportunities for regional cooperation. Led by Coen Smit from Royal HaskoningDHV, the participants identified barriers in implementing this new technology from an organisational and civil society perspective. After that, the participants placed these barriers on a Change Curve, a powerful model used to understand the stages of personal transition and organization stage. Using the Change Curve, we wanted to give Mike some concrete guidance on where to focus his interventions on within the organisation. The barriers were categorised in four phases:

- Awareness: associated with anxiety and denial;

- Desire: associated with emotion and fear;

- Knowledge & ability: associated with acceptance, realisation and energy;

- Reinforcement: associated with growth.

Insights and next steps

In the case of digital identity and the implementation of eID’s, such as Yivi, it appears that most of the barriers are related to the first phase of awareness. Think of: little knowledge about digital identity and current privacy risks, and a lack of trust in a new technology. Communication is crucial to overcome barriers in the awareness. To the user, but also internally to employees and the management. Directors often also know too little about the topic of digital identity.

By looking at the different phases in the change process, we have become aware of the obstacles and thought about possible solutions. But we are still a long way from full implementation and acceptance of this new innovation. For that, we need different perspectives from business, governments and knowledge institutions. This way, we can start creating more awareness about digital transformations and identity in general, which will most likely lead to wishes for more privacy-friendly and easier way of identifying online. Besides focusing on creating more awareness about our digital identity, another possible next step is to organise a more in-depth session (deepdive) with all governmental organisations in the Amsterdam Smart City network.

Do you have any tips or questions in relation to Mike’s project about Digital Identity and electronic Identification? Please get in touch with me through sophie@amsterdamsmartcity.com or leave a comment below.

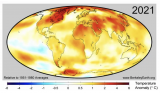

How to live with global warming larger then 3 degrees C

In my previous post (in Dutch) I summarized the main conclusions of the IPCC's Final Report: The probability that the world will have warmed by more than three degrees by 2100 is much greater than that we hold it at 1 1/2 degrees Celsius. In this post I will discuss the consequences of this for the world, whether there is still a way out and what the consequences are for Dutch policy.

Demoday #19: CommuniCity worksession

Without a doubt, our lives are becoming increasingly dependent on new technologies. However, we are also becoming increasingly aware that not everyone benefits equally from the opportunities and possibilities of digitization. Technology is often developed for the masses, leaving more vulnerable groups behind. Through the European-funded CommuniCity project, the municipality of Amsterdam aims to support the development of digital solutions for all by connecting tech organisations to the needs of vulnerable communities. The project will develop a citizen-centred co-creation and co-learning process supporting the cities of Amsterdam, Helsinki, and Porto in launching 100 tech pilots addressing the needs of their communities.

Besides the open call for tech-for-good pilots, the municipality of Amsterdam is also looking for a more structural process for matching the needs of citizens to solutions of tech providers. During this work session, Neeltje Pavicic (municipality of Amsterdam) invited the Amsterdam Smart City network to explore current bottlenecks and potential solutions and next steps.

Process & questions

Neeltje introduced the project using two examples of technology developed specifically for marginalised communities: the Be My Eyes app connects people needing sighted support with volunteers giving virtual assistance through a live video call, and the FLOo Robot supports parents with mild intellectual disabilities by stimulating the interaction between parents and the child.

The diversity of the Amsterdam Smart City network was reflected in the CommuniCity worksession, with participants from governments, businesses and knowledge institutions. Neeltje was curious to the perspectives of the public and private sector, which is why the group was separated based on this criteria. First, the participants identified the bottlenecks: what problems do we face when developing tech solutions for and with marginalised communities? After that, we looked at the potential solutions and the next steps.

Bottlenecks for developing tech for vulnerable communities

The group with companies agreed that technology itself can do a lot, but that it is often difficult to know what is already developed in terms of tech-for-good. Going from a pilot or concept to a concrete realization is often difficult due to the stakeholder landscape and siloed institutions. One of the main bottlenecks is that there is no clear incentive for commercial parties to focus on vulnerable groups. Another bottleneck is that we need to focus on awareness; technology often targets the masses and not marginalized groups who need to be better involved in the design of solutions.

In the group with public organisations, participants discussed that the needs of marginalised communities should be very clear. We should stay away from formulating these needs for people. Therefore, it’s important that civic society organisations identify issues and needs with the target groups, and collaborate with tech-parties that can deliver solutions. Another bottleneck is that there is not enough capital from public partners. There are already many pilots, but scaling up is often difficult.. Therefore solutions should have a business, or a value-case.

Potential next steps

What could be the next steps? The participants indicated that there are already a lot of tech-driven projects and initiatives developed to support vulnerable groups. A key challenge is that these initiatives are fragmented and remain small-scale because there is insufficient sharing and learning between them. A better overview of what is already happening is needed to avoid re-inviting the wheel. There are already several platforms to share these types of initiatives but they do not seem to meet the needs in terms of making visible tested solutions with most potential for upscaling. Participants also suggested hosting knowledge sessions to present examples and lessons-learned from tech-for-good solutions, and train developers to make technology accessible from the start. Legislation can also play a role: by law, technology must meet accessibility requirements and such laws can be extended to protect vulnerable groups. Participants agreed that public authorities and commercial parties should engage in more conversation about this topic.

In response to the worksession, Neeltje mentioned that she gained interesting insights from different angles. She was happy that so many participants showed interest in this topic and decided to join the session. In the coming weeks, Neeltje will organise a few follow-up sessions with different stakeholders. Do you have any input for her? You can contact me via sophie@amsterdamsmartcity.com, and I'll connect you to Neeltje.

The Public Stack: a Model to Incorporate Public Values in Technology

Public administrators, public tech developers, and public service providers face the same challenge: How to develop and use technology in accordance with public values like openness, fairness, and inclusivity? The question is urgent as we continue to rely upon proprietary technology that is developed within a surveillance capitalist context and is incompatible with the goals and missions of our democratic institutions. This problem has been a driving force behind the development of the public stack, a conceptual model developed by Waag through ACROSS and other projects, which roots technical development in public values.

The idea behind the public stack is simple: There are unseen layers behind the technology we use, including hardware, software, design processes, and business models. All of these layers affect the relationship between people and technology – as consumers, subjects, or (as the public stack model advocates) citizens and human beings in a democratic society. The public stack challenges developers, funders, and other stakeholders to develop technology based on shared public values by utilising participatory design processes and open technology. The goal is to position people and the planet as democratic agents; and as more equal stakeholders in deciding how technology is developed and implemented.

ACROSS is a Horizon2020 European project that develops open source resources to protect digital identity and personal data across European borders. In this context, Waag is developing the public stack model into a service design approach – a resource to help others reflect upon and improve the extent to which their own ‘stack’ is reflective of public values. In late 2022, Waag developed a method using the public stack as a lens to prompt reflection amongst developers. A more extensive public stack reflection process is now underway in ACROSS; resources to guide other developers through this same process will be made available later in 2023.

The public stack is a useful model for anyone involved in technology, whether as a developer, funder, active, or even passive user. In the case of ACROSS, its adoption helped project partners to implement decentralised privacy-by-design technology based on values like privacy and user control. The model lends itself to be applied just as well in other use cases:

- Municipalities can use the public stack to maintain democratic approaches to technology development and adoption in cities.

- Developers of both public and private tech can use the public stack to reflect on which values are embedded in their technology.

- Researchers can use the public stack as a way to ethically assess technology.

- Policymakers can use the public stack as a way to understand, communicate, and shape the context in which technology development and implementation occurs.

Are you interested in using the public stack in your own project, initiative, or development process? We’d love to hear about it. Let us know more by emailing us at publicstack@waag.org.

The 100 Intelligent Cities Challenge: Looking Back & Looking Forward

Over the past 2.5 years, the 100 Intelligent Cities Challenge (ICC) of the European Commission’s DG GROW (Directorate General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs) brought together 136 cities in a peer network aimed at transitioning to the green economy.

The main beneficiaries of the program were the 80 core cities that received policy advice and project implementation support. Additionally, all ICC participants engaged in collective learning and knowledge exchange during a series of “City Labs”.

The Role of Amsterdam Metropolitan Region (MRA)

The MRA, represented by Amsterdam Economic Board and Amsterdam Smart City program participated in the ICC as one of sixteen mentors, sharing experiences and best practices throughout the ICC journey. Thirteen experts and stakeholders from MRA contributed to sixteen knowledge-sharing sessions on topics such as local green deals, multi-stakeholder governance, up-skilling & re-skilling, smart mobility, circular economy, and citizen-led initiatives. Amsterdam Smart City and Amsterdam Economic Board also shared knowledge and advice in bilateral meetings with several ICC core cities and participated in the ICC Advisory Board.

Closing Conference

The closing conference of the first phase of the ICC took place in Barcelona during the Smart City Expo World Congress on November 15-16. The conference brought together 40 European mayors, vice-mayors, political representatives, and city leaders. Marja Ruigrok, vice-mayor of the city of Haarlemmermeer, shared MRA’s experience and approach on multi-stakeholder collaboration and several Green Deals initiated by Amsterdam Economic Board. The development of Local Green Deals has become a cornerstone of the ICC which supported 42 cities in designing Green Deals through the development of a Green Deals Blueprint, and tailored support.

Looking Forward to Phase 2 of ICC

In Barcelona, the European Commission confirmed that the second phase of the ICC initiative will start in 2023. Phase 2 will focus on strengthening the existing network of cities and improving the ICC methodology for city-to-city learning, collaboration, and capacity building. Phase 2 also aims to ensure and improve complementarity between the ICC and other EU initiatives, particularly the 100 Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission.

For more information about the first phase of the ICC, visit:

• ICC Website: https://www.intelligentcitieschallenge.eu/

• ICC Project on ASC platform: https://amsterdamsmartcity.com/updates/project/the-100-intelligent-cities-challenge

Stay up to date

Get notified about new updates, opportunities or events that match your interests.