Stay in the know on all smart updates of your favorite topics.

“We’re not just creating technology for cities—we’re creating better cities for people.” From Global Goals to Local Action: How Amsterdam Is Building a Smarter, Fairer City

As the world grapples with massive challenges—climate change, rapid urbanisation, digital disruption, and growing inequality—some cities are not waiting for top-down solutions. They are rolling up their sleeves and experimenting with new ways to improve life for everyone, block by block. Amsterdam is one of those cities.

That’s why I was proud to share Amsterdam InChanges approach to smart, inclusive urban innovation at the #CIPPCD2025 conference in Aveiro.

Through our open innovation platform, <strong>Amsterdam InChange</strong>, the city has become a global leader in turning lofty global ambitions into practical, local action. But Amsterdam’s model isn’t built around flashy tech or utopian blueprints. Instead, it’s grounded in an essential question: How can we use innovation to improve people’s everyday lives?

Local Action for Global Challenges

Amsterdam understands that the climate crisis, digital transition, and social inequality can’t be solved by government alone—or by technology alone. That’s why it launched Amsterdam Smart City in 2009 as a public-private partnership. What began as small-scale energy-saving pilots has grown into a community of over 8,500 members, coordinating more than 300 projects across the city and beyond.

The approach is rooted in co-creation. Citizens, companies, knowledge institutions, and government actors come together to design, test, and scale solutions that serve the public good. The values that guide the network are clear: people first, openness, transparency, learning by doing, and public value.

The Doughnut as a Compass

Amsterdam was the first city in the world to embrace Doughnut Economics as a guiding framework. The “City Doughnut,” developed with economist Kate Raworth, helps policymakers balance the city’s ecological footprint with the social foundations that all citizens need: housing, education, health, equity, and more. It’s a tool to align every local decision with both planetary boundaries and human dignity.

This framework has inspired circular construction strategies, neighbourhood energy co-ops, and more inclusive procurement policies. It shows that global concepts can become real when grounded in local practice.

Making Innovation Inclusive

One of Amsterdam’s core beliefs is that smart cities must be <strong>inclusive cities</strong>. That means tackling issues like <strong>mobility poverty</strong>, where rising transport costs and digital-only services make it harder for low-income or elderly residents to get around.

Through the <strong>Mobility Poverty Challenge</strong>, Amsterdam partnered with the Province of North Holland and researchers from DRIFT to understand where and how exclusion occurs—and to design better public mobility systems. Pilot ideas like a “Mobility Wallet” (a subsidy for essential travel) and more inclusive digital apps emerged from real conversations with affected residents.

The same inclusive mindset guides Amsterdam’s digital transformation. In the suburb of Haarlemmermeer, officials flipped the script on e-government. Instead of asking citizens to become “digitally skilled,” they asked how government systems could become more <strong>humane</strong>. This led to simplified interfaces, better access to services, and ultimately more trust.

Responsible Tech and Energy from the Ground Up

Tech transparency is another pillar of the Amsterdam model. The city runs the world’s first <strong>Algorithm Register</strong>, giving the public insight into how AI and automated systems are used in services—from traffic enforcement to housing applications. Anyone can access this register, offer feedback, and better understand how digital decisions are made.

In the energy space, the city supports both bold innovation and careful upscaling. At the <strong>Johan Cruijff ArenA</strong>, used electric vehicle batteries store solar energy, powering concerts and matches with clean backup power. At the same time, a coalition of partners led by Amsterdam InChange is working to scale up Local Energy Systems by collecting lessons learned and creating a toolkit for community-led energy.

What Makes It Work?

If there’s one secret to Amsterdam’s success, it’s the governance model: small, neutral facilitation teams guiding large multi-stakeholder coalitions, anchored by public trust and shared purpose. Regular Demo Days allow project teams to showcase progress, get feedback, and adapt. This culture of transparency and iteration helps avoid the so-called “innovation graveyard,” where pilot projects go to die.

The city also embraces failure—as long as it’s shared and learned from. Reports like “Organising Smart City Projects” openly list lessons, from the importance of strong leadership to the need for viable business models and continuous user involvement.

An Invitation to Other Cities

Amsterdam’s smart city is not a blueprint—it’s a mindset. Start with your biggest local challenge. Bring the right people together. Make space for experimentation. Build bridges between local and global. And, above all, put citizens at the centre.

As international smart city ambassador Frans-Anton Vermast puts it: “We’re not just creating technology for cities—we’re creating better cities for people.”

The III International Conference on Public Policies and Data Science

Building local mini-economy within planetary boundaries

Scroll naar beneden voor de Nederlandse versie

Growth is an end in itself, dictates the current economic model. For only growth would keep our economy going and be indispensable to further sustainability. At the same time, our planet is being depleted by this drive for green growth.

Is it time to abandon economic growth as a social ideal? And then what are workable, more social alternatives?

More and more business owners are opting for sustainable operations. They settle for less financial gain to do valuable work with positive social and environmental impact. The rise of the commons movement, housing-, energy- and food cooperatives, as well as social initiatives in health and welfare, show that people want to stand together for values other than financial gain.

Achievable and real alternatives

New economic models offer different perspectives for considering the economy as part of a society. They offer tools to make that economy more equitable and sustainable. Yet the new economic thinking is still often dismissed as unrealistic and unachievable. Only by trying out these theories in practice can we demonstrate that these are real alternatives.

New economic thinking, New economic acting

To experiment with new economic theory and models in practice, the Amsterdam Economic Board has started the New Economic Models exploration. In April, we introduced the living lab project “New Economic Thinking, New Economic Acting” at the Marineterrein in Amsterdam. In this we work on socio-economic experiments, together with AMS Institute, AHK Culture Club, And The People, Bureau Marineterrein, Kennisland, The Next Speaker and the knowledge coalition ‘Art, Tech & Science’.

The Marineterrein is the ideal place to do this because it is an official experiment site. Moreover, companies located here are often already working on circular and social projects. Cultural institutions and organisations at the Marineterrein, in turn, can represent what thriving without economic growth could look like and fuel our desire for a new economy.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bouwen aan lokale mini-economie binnen planetaire grenzen

Groei is een doel op zich, dicteert het huidige economische model. Want alleen groei zou onze economie draaiende houden en onmisbaar zijn om verder te verduurzamen. Tegelijkertijd raakt onze planeet uitgeput door die drang naar groene groei.

Wordt het tijd om economische groei als maatschappelijk ideaal los te laten? En wat zijn dan werkbare, socialere alternatieven?

Steeds meer ondernemers kiezen voor een duurzame bedrijfsvoering. Zij nemen genoegen met minder financiële winst om waardevol werk te kunnen doen, met positieve sociale en ecologische impact. De opkomst van de commons-beweging, woon-, energie- en voedselcoöperaties en maatschappelijke initiatieven in zorg en welzijn, laten zien dat mensen zich samen sterk willen maken voor andere waarden dan financieel gewin.

Haalbare en reële alternatieven

Nieuwe economische modellen bieden andere perspectieven om de economie als onderdeel van een samenleving te beschouwen. Ze bieden handvatten om die economie rechtvaardiger en duurzamer in te richten. Toch wordt het nieuwe economisch denken nog vaak weggezet als onrealistisch en niet haalbaar. Alleen door deze theorieën in de praktijk uit te proberen kunnen we aantonen dat dit reële alternatieven zijn.

Nieuw economisch denken, Nieuw economisch doen

Om te kunnen experimenteren met nieuwe economische theorie en modellen in de praktijk, verkent Amsterdam Economic Board deze in de verkenning Nieuwe economische modellen. In april introduceerden we het proeftuinproject ‘Nieuw economisch denken, Nieuw economisch doen’ op het Marineterrein in Amsterdam. Hierin werken we aan sociaaleconomische experimenten, samen met AMS Institute, AHK Culture Club, And The People, Bureau Marineterrein, Kennisland, The Next Speaker en de kenniscoalitie ‘Art, Tech & Science’.

Het Marineterrein is de ideale plek om dit te doen, omdat het een officieel ‘experimentterrein’ is. Bovendien zijn de hier gevestigde bedrijven vaak al bezig met circulaire en sociale projecten. Culturele instellingen en organisaties op het Marineterrein kunnen op hun beurt verbeelden hoe bloei zonder economische groei er uit kan zien en ons verlangen aanwakkeren naar een nieuwe economie.

Demoday #23: Co-creating with residents in the heat transition

The heat transition is in full swing. Municipalities want their residents off the gas and want them to switch to renewable sources of heat. Unfortunately, heat grids have often led to frustrated residents. Which in turn has led to delayed or cancelled plans for the municipality.

Dave van Loon and Marieke van Doorninck (Kennisland) have looked into the problems surrounding heat grids and came up with a plan. In this Demoday work-session we dived into the problems surrounding heat grids and their plan to solve them. The session was moderated by our own Leonie van Beuken.

Why residents get frustrated with heat grid plans

Involving residents in the planning of a heat grid is difficult. It takes a lot of time and effort and the municipality is often in a hurry. This is why they choose for a compromise in which they already make the plan, but try to involve citizens at the end part. However, this leads to residents not having anything to say in the plans. They can block the plans, but they can’t really make changes. This leads to a lot of dissatisfaction.

This top-down approach doesn't seem to be ideal for involving residents in the heat transition. That's why Kennisland is working on developing a plan for early collaboration with residents in the heat transition of neighbourhoods, with a focus on connecting with the community's concerns.

They have seen that this kind of approach can be successful by looking at the K-buurt in Amsterdam-Zuid-Oost. In the initial stages, the first plan for the K-buurt didn't gain much traction. However, when they shifted towards a more collaborative approach, people felt empowered to engage, leading to a more meaningful participation process. Instead of traditional town hall meetings, discussions took place in community spaces like the local barber shop. This shift towards genuine participation and co-creation has resulted in a much-improved end product, one that residents truly support and believe in.

The plan for co-creation in the heat transition

The plan that Kennisland came up with consists of a few key points that are necessary for success:

• Engage with residents early on in the process.

• Also consider other issues in the neighbourhood. There might be more pressing concerns for the residents themselves.

• Ensure accessibility for everyone to participate.

• Truly collaborate on developing a list of requirements.

• Harness creativity.

• Work in a less compartmentalized manner.

They aim to form a neighbourhood alliance and organize a community council. Together a plan can be made for the neighbourhood that all residents can get behind.

This plan might take a bit longer at the start, but that investment in time will pay itself back in the end.

SWOT analysis of co-creation plan

After Dave and Marieke explained their plan we did a SWOT analysis with the group. We looked at the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats of the plan.

The main strength that was pointed out was the ability to make a plan together with the residents. The residents experience the neighbourhood differently than a government official, which makes the final plan more beneficial to everyone.

The weaknesses the group saw in the plan were mainly that this could potentially slow down the process. Should we maybe do less participation instead of more and use force to get this heat transition going?

There were a lot of opportunities identified for this plan. The quality of the plan (and the neighbourhood) can greatly increase. By slowing down at the start we can actually accelerate and improve the neighbourhood on many levels. This plan also offers a great learning experience.

Finally, we went into the threats. One of the big threats that was pointed out was the lack of trust. If residents don’t trust the municipality and the process then it will never be possible to let this plan succeed. The explanation to residents also needs to be understandable. The explanation around a heat grid can get technical very quickly, and residents often don’t have the background to understand everything. The last threat that was pointed out was that if you get a lot of input from the residents for the plan, you also have to do something with that, and still be realistic. You have to work hard to manage expectations.

We completed the session by asking the participants if they knew any partners and places to collaborate with for this plan, or if they had any other ideas to make this plan successful.

We would now like to ask the same questions to you! Do you know someone who would like to partner up with Kennisland, do you know a place where this plan can be tested, or do you have any other ideas? Let us know by contacting me at noor@amsterdamsmartcity.com.

Demoday #23 Knowledge Session: An Introduction to Socratic Design

During our 23rd Demo Day on April 18, 2024, Ruben Polderman told us more about the philosophy and method of Socratic Design. It's important for a city to collectively reflect on a good existence. Socratic Design can be a way to think about this together, collectively.

Thinking and Acting Differently with Socratic Design

Together with his colleagues at the Digitalization & Innovation department of the Municipality of Amsterdam, Ruben explored how a city should deal with innovation and digitalization. Things were progressing well. The municipality could act swiftly; for example, promising Smart Mobility research and innovation projects were initiated with new partners. However, the transitions are heading in various directions, and progress remains limited. No matter how groundbreaking innovation is, there's a danger in trying to solve problems with the same mindset that caused them. The ability to perceive or think differently is therefore crucial. More crucial, even, than accumulated knowledge, as filosopher David Bohm suggested.

Through Socratic Design, we can collectively improve the latter. You work on your own presuppositions, enhance your listening skills, and deepen your understanding of our current dominant narratives to create new narratives and practices. Ruben guided us through examples and exercises to help us understand what narratives and presuppositions entail.

Narratives

"We think we live in reality, but we live in a narrative," Ruben proposes to the group. What we say to each other and how we interact creates a culture that shapes the group and its actions. Narratives are stories that guide our culture, values, thoughts, and actions. They are paradigms so deeply rooted that we no longer question them and sometimes believe there is no alternative. Our current dominant narrative has significant consequences for the Earth and humanity, and although it seems fixed, we can also create new narratives together if we choose to do so.

We must fundamentally seek a good existence within safe ecological boundaries. This should go beyond the transitions we are currently favouring, which sustain our lifestyle but just make it less harmful for the environment. If we want to create new stories with new, positive human perceptions and lifestyles, we must first examine our current narrative and presuppositions. We will need to deconstruct our current ways of living and thinking, much like the Theory U method mentioned during the previous Knowledge Session (see our recap article of this session).

Understanding Presuppositions

Ruben showed us various themes and images to collectively practice recognizing presuppositions. For example, a photo of a medical patient and doctors in action demonstrates that our feeling of "to measure is to know" is also crucial in healthcare. The doctors focus on the screen, the graph, the numbers, and therefore have less focus on the patient; the human, themselves. A photo of the stock market, where a group of men is busy trading stocks, also illustrates our idea of economic growth. Here too, there is a fixation on numbers. Ideally, they're green and going up, but meanwhile, we can lose sight of what exactly we're working towards and what exactly it is that we’re ‘growing’.

As a group, we discussed some presuppositions we could find in our field of work. For example, we talked about our need for and appreciation of objective data, and technologism; the belief in solutions rooted in technology and digitalization.

Fundamental Presupposition Shifts and New Narratives

If you flip a presupposition like Technologism and suggest that Social Interaction could be our salvation and solution to many of our problems, you set off a fundamental presupposition shift. If you translate this into practical actions or experiments, you can collectively understand how a newly created presupposition functions. As a group, we worked on this. During this session, I myself worked with an example from the field of mobility.

If I were to apply this new presupposition in the field of mobility and we look at the development of cars, perhaps we shouldn't go towards autonomous vehicles (technologism), but look for ways to motivate and strengthen carpooling (social interaction). As an experiment, you could, for example, set up an alternative to the conventional car lease plan. Employees of an organization don't all get the option to lease a car; instead, it's considered who could commute together, and there's a maximum of 1 car for every 4 employees per organization. Just like going to an away game with your soccer team on Sundays as a kid; enjoyable!

Read More

This session was an introduction and gave us a good initial understanding of this philosophy and method, but there's much more to discover. The method also delves into how presuppositions are deeply rooted in us, how we validate this with feeling in our bodies, and dialogue methods to collectively arrive at new values and narratives. There's more explained about Socratic Design on Amsterdam's Open Research platform.

Join AMS Institute's Scientific Conference, hosted by TU Delft, Wageningen University & Research, MIT and the City of Amsterdam.

Do you want to learn from and network with the best researchers and scientists working to tackle pressing urban challenges?

AMS Institute, is organizing the AMS Scientific Conference from April 23-25 at the Marineterrein, Amsterdam, to address pressing urban challenges. The event is organized in collaboration with the City of Amsterdam.

The conference brings together leading institutions in urban research and innovation, thought leaders, municipalities, researchers, and practitioners to explore innovative solutions for sustainable development in Amsterdam and other global cities.

Keynotes, research workshops, learning tracks, and special sessions will explore the latest papers in the fields of mobility, circularity, energy transition, climate adaptation, urban food systems, digitization, diversity, inclusion, living labs experimentation, and transdisciplinary research.

Attendees can expect to gain valuable insights into cutting-edge research and engage in meaningful discussions with leading experts in their field. You can see the full program and all available sessions here.

This year's theme is 'Blueprints for messy cities? Navigating the interplay of order and messiness'.

The program

Day 1: The good, the bad, and the ugly

Keynotes by Paul Behrens of Leiden University and Elin Andersdotter Fabre of UN-Habitat will be followed by a city panel including climate activist <strong>Hannah Prins</strong>. The first day concludes with a dinner at the Koepelkerk in Amsterdam: you're welcome to join our three-course meal with a 50 euro ticket.

Day 2️: Amazing discoveries

Keynotes by Carlo Ratti of MIT and Sacha Stolp of the Municipality of Amsterdam discuss innovation and research in cities. <strong>Corinne Vigreux</strong>, co-founder of TomTom, and Erik Versnel from Rabobank will participate in the city panel.

Day 3️: We are the city

Keynotes by Paul Chatterton of Leeds University and Victor Neequaye Kotey Deputy Director of the Waste Management Department of the Accra Metropolitan Assembly, Ghana. They discuss how we shape the future of our cities together. This will be followed by a city panel including Ria Braaf-Fränkel of WomenMakeTheCity and prof. dr. Aleid Brouwer of the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen.

To buy tickets: You can secure your conference tickets through our website.

Dinner tickets: On April 23 we’re hosting a dinner at the Koepelkerk in Amsterdam. Tickets for this can be added to your conference pass or bought separately.

The global distribution of the 15-minute city idea 5/7

A previous post made it clear that a 15-minute city ideally consists of a 5-minute walking zone, a 15-minute walking zone, also a 5-minute cycling zone and a the 15-minute cycling zone. These three types of neighbourhoods and districts should be developed in conjunction, with employment accessibility also playing an important role.

In the plans for 15-minute cities in many places around the world, these types of zones intertwine, and often it is not even clear which type of zone is meant. In Paris too, I miss clear choices in this regard.

The city of Melbourne aims to give a local lifestyle a dominant place among all residents. Therefore, everyone should live within at most 10 minutes' walking distance to and from all daily amenities. For this reason, it is referred to as a 20-minute city, whereas in most examples of a 15-minute city, such as Paris, it is only about <strong>the round trip</strong>. The policy in Melbourne has received strong support from the health sector, which highlights the negative effects of traffic and air pollution.

In Vancouver, there is talk of a 5-minute city. The idea is for neighbourhoods to become more distinct parts of the city. Each neighbourhood should have several locally owned shops as well as public facilities such as parks, schools, community centres, childcare and libraries. High on the agenda is the push for greater diversity of residents and housing types. Especially in inner-city neighbourhoods, this is accompanied by high densities and high-rise buildings. Confronting this idea with reality yields a pattern of about 120 such geographical units (see map above).

Many other cities picked up the idea of the 15-minute city. Among them: Barcelona, London, Milan, Ottawa, Detroit and Portland. The organisation of world cities C40 (now consisting of 96 cities) elevated the idea to the main policy goal in the post-Covid period.

All these cities advocate a reversal of mainstream urbanisation policies. In recent decades, many billions have been invested in building roads with the aim of improving accessibility. This means increasing the distance you can travel in a given time. As a result, facilities were scaled up and concentrated in increasingly distant places. This in turn led to increased congestion that negated improvements in accessibility. The response was further expansion of the road network. This phenomenon is known as the 'mobility trap' or the Marchetti constant.

Instead of increasing accessibility, the 15-minute city aims to expand the number of urban functions you can access within a certain amount of time. This includes employment opportunities. The possibility of working from home has reduced the relevance of the distance between home and workplace. In contrast, the importance of a pleasant living environment has increased. A modified version of the 15-minute city, the 'walkable city' then throws high hopes. That, among other things, is the subject of my next post.

Data Dilemma's verslag: Data voor leefbare straten, buurten en steden

Hoe zetten we Data in voor leefbare straten, buurten en steden? En heb je die datasets echt zo hard nodig? "Of heb je de bewoner al voor je, kun je aan tafel, en kun je gewoon samen van start gaan met een idee?" (aldus Luc Manders).

Op 29 februari kwamen we in een volle Culture Club (Amsterdamse Hogeschool voor de Kunsten) bijeen om het te hebben over Data en Leefbare Wijken. In een fijne samenwerking met onze partner Hieroo en SeederDeBoer nodigden we verschillende sprekers en onze communities uit op het Marineterrein Amsterdam.

Leefbare wijken op de kaart en het visueel maken van data.

Sahar Tushuizen en Martijn Veenstra (Gemeente Amsterdam) namen verschillende kaarten mee om ons te laten zien hoe visuele data weergaven worden ingezet bij het maken van verstedelijkingsstrategieën, omgevingsvisies en beleid.

Een stad is opgebouwd uit verschillende wijken en gebieden. Simpel gezegd; in sommige wijken wordt vooral ‘gewoond’, in andere gebieden vooral gewerkt, en in sommige wijken vindt er een mooie functiemenging plaats. Samen zorgt dit voor een balans, en maakt het de stad. Maar vooral de wijken met een functiemix maken fijne wijken om in te leven, aldus Sahar en Martijn. Door de spreiding van functies visueel te maken met kaarten kan je inzichtelijk maken hoe het nu is verdeeld in Amsterdam, en inspelen op de gebieden waar functiemenging misschien wel erg achterloopt. Stedelijke vernieuwing is uiteindelijk ook een sociaal project. Het gaat niet alleen over stenen plaatsen, we moeten het ook koppelen aan bereikbaarheid en/van voorzieningen.

Sahar en Martijn gebruiken hun kaarten en gekleurde vlekken om de leefbaarheid van wijken terug te laten komen in Amsterdamse visies. Maar de kaarten vertellen niet het hele verhaal, benoemen ze op het einde van hun presentatie. “We gaan ook in gesprek met inwoners hoe functies en buurtactoren worden ervaren en gewaardeerd”. Dit maakte een mooi bruggetje naar de volgende twee sprekers.

Welzijnsdashboard.nl

Hebe Verrest (Professor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam) nam ons daarna mee in het verhaal van welzijnsdashboard.nl. Een samenwerkingsproject tussen Amsterdamse buurtbewoners (Venserpolder) en onderzoekers van de UvA.

Dit project vond haar oorsprong in twee ontwikkelingen: Er zijn de bewoners die zich niet altijd kunnen herkennen in het beeld dat over hun wijk en economisch welzijn bestaat, en zich niet gehoord voelen in verbeterprocessen in hun eigen omgeving. En dan zijn er ook de wetenschappers die merkten dat data over levens vaak nauw economisch gestuurd is. De data en het meten ervan gebeurt op een hoog schaalniveau, en dus vroegen onderzoekers zich af hoe je op lokale schaal kunt meten met meetinstrumenten die van nature democratischer zijn.

Onderzoekers van de UvA en bewoners van de wijk Venserpolder (Amsterdam Zuid-Oost) creëerden daarom samen een dashboard. De bewoners mochten meedenken wat het dashboard allemaal voor functies had, en het belangrijkste; ze mochten samen de variabele indicatoren bedenken die ze van belang vonden voor de buurt. Met behulp van de samengestelde indicatoren konden ze hun (persoonlijke) ervaringen vertalen naar data over de leefbaarheid en staat van hun buurt. De bewoners ervaarden meer zeggenschap en gehoor, en werden steeds beter in het werken met het dashboard en het vertalen van persoonlijke ervaringen naar wat algemenere data. De onderzoekers leerden met het dashboard over het ophalen van subjectieve, maar bruikbare data. En ten slotte was het voor beleidsmedewerkers en experts een mooie middel om een mix van ‘verhalen uit de buurt’ en abstractere data te verkrijgen.

Het project loopt nog steeds en zal worden toegepast op verschillende buurten. Voor nu sloot Hebe haar presentatie af met een belangrijke learning: "Wat de bewoners belangrijke variabelen vinden, lijken ook die te zijn waar een probleem speelt".

Van data naar datum

Ten slotte hield Luc Manders (Buurtvolk) een inspirerend pleidooi over zijn ervaringen met interventies in kwetsbare wijken. Hoewel data zeker bruikbaar kan zijn voor het signaleren en voorspellen van problemen, wilde hij het publiek tonen dat het uiteindelijk vooral gaat om het in gang zetten van een dialoog en interventie, samen mét de buurtbewoners.

Data kan zeker bruikbaar zijn voor het signaleren en voorspellen van problemen. Het in kaart brengen van risico’s in wijken kan ons tonen waar actie nodig is, maar uiteindelijk gaat leefbaarheid en welzijn over een geleefde werkelijkheid. Het gevaar is dat we blindstaren op data en kaarten en dat we de kaarten ‘beter’ maken, in plaats van iets echt in gang zetten in de wijk zelf. Want ook daar waar de cijfers verbetering aangeven, kunnen nog steeds dingen spelen die we niet weten te vangen met onze data en meetinstrumenten.

Luc noemde zijn presentatie daarom ‘Van data naar datum’. We zouden het iets minder mogen hebben over data, en het méér moeten hebben over de datum waarop we van start gaan met een project, een initiatief of een dialoog met buurtbewoners. Het liefst gaan we zo snel mogelijk met de bewoner aan tafel en zetten we iets in gang. Het begint bij het delen van verhalen en ervaringen over de situatie in de wijk, deze gaan verder dan cijfers die hoogover zijn opgehaald. Dan kan er samen met de bewoners worden nagedacht over een interventie die de wijk ten goede zou komen. Luc benadrukte hierbij ook dat we nog in te korte termijnen denken. Projecten van 2 jaar en professionals die zich 2 jaar in een wijk vastbijten vinden we al een mooie prestatie. Maar interventies in het sociaal domein hebben langer nodig. We zouden moeten denken in investeringen van bijvoorbeeld 10 jaar, zo kunnen we samen met bewoners meer leren van elkaar en meer vertrouwen op bouwen, en hoeven we niet steeds het wiel opnieuw uit te vinden.

Luc deelde ervaringsvoorbeelden, waarbij kleine interventies positieve bij-effecten in gang zetten, en moedigde het publiek aan: "Kosten en investeringen zullen aan de voorkant komen en blijven. Maar blijf het langdurig doen, leer samen met de bewoners, en denk aan het sneeuwbaleffect dat kleine interventies in gang zetten".

Dank aan de sprekers voor hun verhalen en het publiek voor de levendige discussies na afloop. Wil je bij onze volgende Data Dilemma's zijn? De volgende editie van deze serie open events vindt plaats op 30 mei. Het onderwerp en de sprekers worden binnenkort bekendgemaakt via ons platform en LinkedIn. Tot dan!

New article "Guidelines for a participatory Smart City model to address Amazon’s urban environmental problems"

Dear Amsterdam Smart City Managers and Members,

As a member of your digital platform, I would like to sincerely thank you for the insightful emails and contents you provide to members like myself throughout the year.

I am delighted to share with you my latest published article, "Guidelines for a participatory Smart City model to address Amazon’s urban environmental problems," featured in the December 12, 2023 issue of PeerJ Computer Science.

The article can be fully accessed and cited at:

da Silva JG. 2023. Guidelines for a participatory Smart City model to address Amazon’s urban environmental problems. PeerJ Computer Science 9:e1694 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.1694

I welcome you to read my publication and share it with fellow members who may find the digital solutions for the Amazon region useful. Please let me know if you have any feedback or ideas to advance this work.

Sincerely (敬具)

Prof. Jonas Gomes ( 博士ジョナス・ゴメス)

www.jgsilva.org

UFAM/FT Industrial Engineering Department (Manaus-Amazon-Brazil)

The University of Manchester/MIOIR/SCI/AMBS Research Visitor 2020/2023

Vaart maken met bestaanszekerheid? Schaal goede initiatieven op!

Welke concrete stappen kan de overheid op korte termijn zetten om kwetsbare burgers te ondersteunen?

Bestaanszekerheid was een van de cruciale thema's tijdens de verkiezingen en zal dat ook tijdens de formatie zijn. Er zijn veel ideeën over lange termijn oplossingen, maar mensen hebben nu direct hulp nodig. Hoe kan de overheid op korte termijn kwetsbare burgers helpen? Schaal succesvolle projecten snel op, benut fondsen beter en maak gebruik van de kracht en invloed van het bedrijfsleven, adviseren John Schattori, Johan Stuiver en Channa Dijkhuis van Deloitte.

In Nederland leven bijna één miljoen mensen onder de armoedegrens. Ook worstelen steeds meer mensen om financieel het hoofd boven water te houden. Uit recent onderzoek van Deloitte blijkt dat van de 5000 ondervraagde huishoudens slechts de helft zonder problemen alle rekeningen kon voldoen. En bijna één op de vijf huishoudens had afgelopen jaar moeite met het betalen van essentiële levenskosten. Dit illustreert dat zelfs in een van de rijkste landen ter wereld een grote groep mensen in aanzienlijke onzekerheid leeft.

Het is dan ook niet verrassend dat 'bestaanszekerheid' een belangrijk thema was in alle verkiezingsprogramma’s. En terecht, want in een wereld van economische onzekerheid en maatschappelijke veranderingen, moeten we mensen beschermen tegen financiële kwetsbaarheid en sociale ontwrichting.

De politieke partijen hebben sterk uiteenlopende oplossingen voor het aanpakken van bestaanszekerheid die vooral gericht zijn op de lange termijn. Zo is een stelselwijziging noodzakelijk om gaandeweg te zorgen voor een eerlijk, eenvoudig en rechtvaardig systeem dat bestaanszekerheid voor iedereen biedt. Maar zo’n verandering is complex en tijdrovend, terwijl er nu een groeiende groep burgers is die direct dringend hulp nodig heeft. Over de vraag wat de overheid op de korte termijn al kan doen, vertellen John Schattorie, Partner Centrale Overheid, Johan Stuiver, Director WorldClass bij de Deloitte Impact Foundation en Channa Dijkhuis, Director Public Sector.

Pak de regie en werk samen

Een eerste stap voor de overheid is om in te zetten op projecten die hun succes al hebben bewezen. Veel experimenten en pilots gericht op het verhogen van bestaanszekerheid vinden plaats op gemeentelijk niveau. Maar wanneer zo'n experiment of pilot slaagt, ontbreekt het vaak aan verantwoordelijkheid voor verdere opschaling, constateren Schattorie, Stuiver en Dijkhuis.

Stuiver: “Dat is kapitaalvernietiging, omdat een geslaagd initiatief daardoor op gemeentelijk niveau blijft hangen, net als de kennis en ervaring. In die leemte, waarbij niemand zich eigenaar voelt en verantwoordelijkheid neemt, kan het Rijk vaker de regie pakken om opschaling mogelijk te maken, in samenwerking met de gemeente waar veel kennis zit.”

Schattorie: “We hebben nu eenmaal verschillende bestuurslagen in Nederland, maar daar moet het Rijk zich niet door laten weerhouden. Zij moet juist over deze lagen heen kijken, succesvolle initiatieven selecteren en onderzoeken wat nodig is om ze op te schalen.”

Innovatieve arbeidsmarktconcepten

Neem het innovatieve arbeidsmarktconcept van de basisbaan. Deze is bedoeld voor mensen die al langdurig in de bijstand zitten en moeilijk aan regulier werk kunnen komen. Dankzij het salaris van de basisbaan zijn zij niet langer afhankelijk van een uitkering. Het werk is van maatschappelijke waarde en verhoogt de leefbaarheid in buurten, denk aan onderhouds- en reparatiewerkzaamheden, zorgtaken en toezicht in de wijk.

Dijkhuis: “Het opschalen van experimenten naar landelijk niveau is primair de verantwoordelijkheid van het Rijk. Zij zijn dan ook aan zet om zelf of in samenwerking met experts de opschaling te realiseren.” Schattorie: “We zien dat betrokkenen bij de basisbaan er netto direct op vooruitgaan wat leidt tot verlaging van tal van maatschappelijke kosten. Dat verdient landelijke opschaling met steun van het Rijk, gemeenten, het bedrijfsleven en maatschappelijke organisaties.”

Stuiver: “De basisbaan is in een aantal gemeenten succesvol, maar heeft nog geen grote navolging gekregen op nationaal niveau. In plaats daarvan ontwikkelen veel gemeenten het concept vaak opnieuw.” Dijkhuis: “Dat is het bekende psychologische effect van not invented here, waarbij nieuwe ideeën worden genegeerd omdat ze elders bedacht zijn. De overheid moet dit effect actief tegengaan.”

Betrek het bedrijfsleven

Een ander inspirerend voorbeeld van een initiatief dat opschaling naar landelijk niveau verdient is Stichting het Bouwdepot. Dat begon als een project van gemeente Eindhoven waarbij dertig thuisloze jongeren een jaar lang 1050 euro per maand ontvingen.

Dijkhuis: “Het merendeel van de jongeren woonde na dat jaar zelfstandig en meer dan de helft was schuldenvrij. Dit laat zien dat als je mensen vertrouwen geeft en voor rust zorgt, ze bewuste keuzes maken.”

Stuiver: “Pas als mensen financiële rust hebben kunnen ze de stap zetten om hun bestaanszekerheid te verbeteren, bijvoorbeeld door eindelijk alle post weer te openen, maatschappelijk actief te worden of zich te oriënteren op scholing of werk.”

De vraag is nu hoe je dergelijke projecten slim opschaalt. Schattorie, Stuiver en Dijkhuis zien een belangrijke rol weggelegd voor het bedrijfsleven en maatschappelijke organisaties. Zij dragen immers al structureel bij aan initiatieven om bestaanszekerheid te verbeteren, bijvoorbeeld in onderwijs, financiële gezondheid, schuldhulpverlening en armoedebestrijding.

Dijkhuis: “Feit is dat in publiek-private samenwerkingen (PPS-en) bestaanszekerheidsvraagstukken doorgaans effectiever, sneller en duurzamer kunnen worden opgelost. Niemand - overheid, bedrijfsleven of onderwijs - kan de huidige vraagstukken alleen oplossen. We hebben elkaar nodig, uit de PPS-en komen nieuwe inzichten en innovaties voort.”

Stuiver: “Vanuit de Impact Foundation werken we bijvoorbeeld samen met onze klanten aan allerlei projecten rond financiële gezondheid voor verschillende doelgroepen, zoals SchuldenLab NL en Think Forward Initiative. Ook werken we met impact ondernemers om ongeziene talenten te helpen die moeite hebben hun plek in de samenleving te vinden.”

Schattorie: “Het is wel nodig dat het bedrijfsleven gebundeld en voor de lange termijn haar bijdrage levert aan dergelijke programma’s, waar zij samen met de overheid de richting en inrichting van de oplossingen bepaalt. Vanuit een gemeenschappelijk belang, resultaatgericht en in onderling vertrouwen. Onze ambitie is dan ook dat we vaker samen met onze klanten gebundeld impact willen maken.” Dijkhuis: “Nu zitten we nog te vaak met een ‘duizend bloemen bloeien-strategie’, het zou veel impactvoller zijn als je dat meer in lijn brengt met elkaar.”

Benut fondsen beter

Volgens Schattorie, Stuiver en Dijkhuis is het essentieel om met een meer geïntegreerde blik te kijken naar wat er nodig is om mensen weer op de been te helpen. Ze benadrukken dat het bedrijfsleven zich medeverantwoordelijk voelt en, mits de juiste randvoorwaarden worden gecreëerd, bereid is om meer te doen dan nu het geval is. Met andere woorden: er is genoeg potentie voor experimentele innovatie, capaciteit en budget. Het is de verantwoordelijkheid van de overheid om de regie nemen en deze zaken samen te brengen, waarbij ook fondsen beter benut kunnen worden.

Schattorie: “Het aantal toeslagen, budgetten en fondsen voor het verhogen van de bestaanszekerheid en verminderen van armoede is enorm. Veel van deze budgetten blijven echter ongebruikt, bijvoorbeeld uit vrees voor de mogelijke effecten op andere toeslagen en kortingen.”

Dijkhuis: “Onbekendheid en complexiteit van de beschikbare financiële steun is een belangrijke reden. Daarnaast is er in een aantal grote steden een versnipperd aanbod van honderden maatschappelijke initiatieven die zich per wijk en doelgroep op specifieke thema’s richten.”

Stuiver: “De communicatie over deze regelingen loopt vaak via kanalen die voor (kwetsbare) burgers moeilijk te vinden zijn. Een oplossing zou zijn om bedragen uit fondsen proactief en automatisch toe te kennen aan diegenen die het nodig hebben. De impact hiervan is direct merkbaar.”

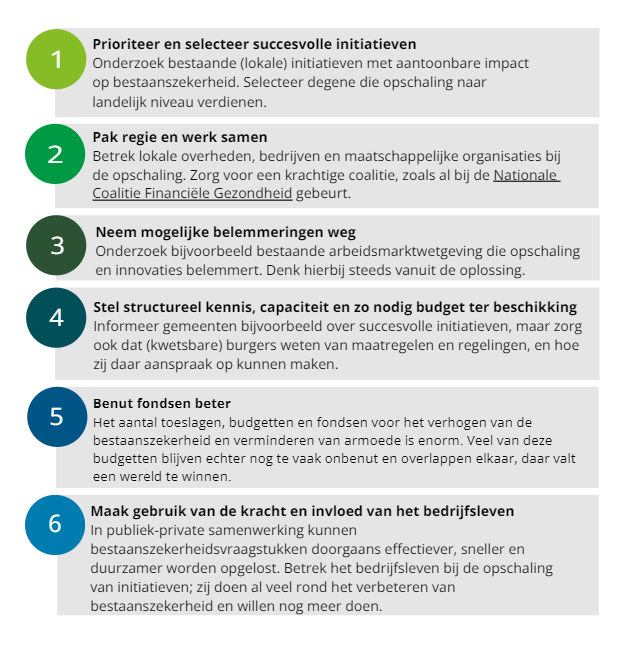

Ondanks de politieke onzekerheden is één ding duidelijk: actie is nu nodig. Zelfs een demissionair kabinet kan initiatief nemen door samenwerking te stimuleren, regie te voeren en de beste initiatieven landelijk uit te rollen, menen Schattorie, Stuiver en Dijkhuis. In onderstaande tabel geven zij een aanzet voor de eerste praktische stappen. Want: bestaanszekerheid mag dan een complex politiek vraagstuk zijn, het is vooral een dringende maatschappelijke behoefte waar elke bestuurder vandaag nog mee aan de slag kan.

Stappen om succesvolle initiatieven op te schalen

First driverless taxis on the road (6/8)

Since mid-2022, Cruise and Waymo have been allowed to offer a ride-hailing service without a safety driver in a quiet part of San Francisco from 11pm to 6am. The permit has now been extended to the entire city throughout the day. The company has 400 cars and Waymo 250. So far, it has not been an unqualified success.

A turbulent start

In a hilarious incident, an empty taxi was pulled over by police; it stopped properly, but kept going after a few seconds, leaving the officers wondering if they should give chase. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is investigating this incident, as well as several others involving Cruise taxis stalling at intersections, and the Fire Department reports 60 incidents involving autonomous taxis.

Pending further investigation, both companies are only allowed to operate half of their fleet. In addition to the fire department and public transport companies, trade unions are also opposed to the growth of autonomous taxis. California's governor has rejected the objections, fearing that BigTech will swap the state for more car-friendly ones. It is expected that autonomous taxis will gradually enter all major US cities, at a rate just below that of Uber and Lyft.

Cruise has already hooked another big fish: In the not-too-distant future, the company will be allowed to operate autonomous taxis in parts of Dubai.

The number of autonomous taxi services in the world can still be counted on one hand. Baidu has been offering ride-hailing services in Wuhan since December 2022, and robot taxis have been operating in parts of Shenzen since then.

Singapore was the first city in the world to have several autonomous taxis operating on a very small scale. These were developed by nuTonomy, an MIT spin-off, but the service is still in an experimental phase. Another company, Mobileye, also plans to start operating in Singapore this year.

The same company announced in 2022 that it would launch a service in Germany in 2023 in partnership with car rental company Sixt 6, but nothing more has been heard. A survey by JD Power found that almost two-thirds of Germans do not trust 'self-driving cars'. But that opinion could change quickly if safety is proven and the benefits become clear.

What is it like to drive a robotaxi?

Currently, the group of robotaxi users is still small, mainly because the range is limited in space and time. The first customers are early adopters who want to experience the ride.

Curious readers: Here you can drive a Tesla equipped with the new beta 1.4 self-driving system, and here you can board a robotaxi in Shenzhen.

The robotaxis work by hailing: You use an app to say where you are and where you want to go, and the computer makes sure the nearest taxi picks you up. Meanwhile, you can adjust the temperature in the car and tune in to your favourite radio station.

Inside the car, passengers will find tablets with information about the journey. They remind passengers to close all doors and fasten their seatbelts. Passengers can communicate with remote support staff at the touch of a button. TV cameras allow passengers to watch. Passengers can end the journey at any time by pressing a button. If a passenger forgets to close the door, the vehicle will do it for them.

The price of a ride in a robotaxi is just below the price of a ride with Uber or Lyft. The price level is strongly influenced by the current high purchase price of a robotaxi, which is about $175,000 more than a regular taxi. Research shows that people are willing to give up their own cars if robotaxis are available on demand and the rides cost significantly less than a regular taxi. But then the road is open for a huge increase in car journeys, CO2 emissions and the cannibalisation of public transport, which I previously called the horror scenario.

Roboshuttles

In some cities, such as Detroit, Austin, Stockholm, Tallinn and Berlin, as well as Amsterdam and Rotterdam, minibuses operate without a driver, but usually with a safety officer on board. They are small vehicles with a maximum speed of 25 km/h, which operate in the traffic lane or on traffic-calmed streets and follow a fixed route. They are usually part of pilot projects exploring the possibilities of this mode of transport as a means of pre- and post-transport.

Free download

Recently, I published a new e-book with 25 advices for improving the quality of our living environment. Follow the link below to download it for free.

A new challenge: Floating neighbourhoods with AMS Institute and municipality of Amsterdam

A lot of what we did in Barcelona was about making connections, sharing knowledge, and being inspired. However, we wouldn’t be Amsterdam Smart City if we didn’t give it a bit of our own special flavour. That’s why we decided to take this inspiring opportunity to start a new challenge about floating neighbourhoods together with Anja Reimann (municipality of Amsterdam) and Joke Dufourmont (AMS Institute). The session was hosted at the Microsoft Pavilion.

We are facing many problems right now in the Netherlands. With climate change, flooding and drought are both becoming big problems. We have a big housing shortage and net congestion is becoming a more prominent problem every day. This drove the municipality of Amsterdam and AMS institute to think outside the box when it came to building a new neighbourhood and looking towards all the space we have on the water. Floating neighbourhoods might be the neighbourhoods of the future. In this session, we dived into the challenges and opportunities that this type of neighbourhood can bring.

The session was split up into two parts. The first part was with municipalities and governmental organisations to discuss what a floating neighbourhood would look like. The second part was with entrepreneurs who specialized in mobility to discuss what mobility on and around a floating neighbourhood should look like.

Part one - What should a floating neighbourhood look like?

In this part of the session, we discussed what a floating district should look like:

- What will we do there?

- What will we need there?

- How will we get there?

We discussed by having all the contestants place their answers to these questions on post-its and putting them under the questions. We voted on the post-its to decide what points we found most important.

A few of the answers were:

- One of the key reasons for a person to live in a floating neighbourhood would be to live closer to nature. Making sure that the neighbourhood is in balance with nature is therefore very important.

- We will need space for nature (insects included), modular buildings, and space for living (not just sleeping and working). There need to be recreational spaces, sports fields, theatres and more.

- To get there we would need good infrastructure. If we make a bridge to this neighbourhood should cars be allowed? Or would we prefer foot and bicycle traffic, and, of course, boats? In this group, a carless neighbourhood had the preference, with public boat transfer to travel larger distances.

Part two - How might we organise the mobility system of a floating district?

In the second part of this session, we had a market consultation with mobility experts. We discussed how to organise the mobility system of a floating neighbourhood:

- What are the necessary solutions for achieving this? What are opportunities that are not possible on land and what are the boundaries of what’s possible?

- Which competencies are necessary to achieve this and who has them (which companies)?

- How would we collaborate to achieve this? Is an innovation partnership suitable as a method to work together instead of a public tender? Would you be willing to work with other companies? What business model would work best to collaborate?

We again discussed these questions using the post-it method. After a few minutes of intense writing and putting up post-its we were ready to discuss. There a lot of points so here are only a few of the high lights:

Solutions:

- Local energy: wind, solar, and water energy. There are a lot of opportunities for local energy production on the water because it is often windy, you can generate energy from the water itself, and solar energy is available as well. Battery storage systems are crucial for this.

- Autonomous boats such as the roboat. These can be used for city logistics (parcels) for instance.

- Wireless charging for autonomous ferry’s.

Competencies:

- It should be a pleasant and social place to live in.

- Data needs to be optimized for good city logistics. Shared mobility is a must.

- GPS signal doesn’t work well on water. A solution must be found for this.

- There needs to be a system in place for safety. How would a fire department function on water for instance?

Collaboration:

- Grid operators should be involved. What would the electricity net look like for a floating neighbourhood?

- How do you work together with the mainland? Would you need the mainland or can a floating neighbourhood be self-sufficient?

- We should continue working on this problem on a demo day from Amsterdam Smart City!

A lot more interesting points were raised, and if you are interested in this topic, please reach out to us and get involved. We will continue the conversation around floating neighbourhoods in 2024.

25. Happiness

This is the 25st and last episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Its topic is happiness. Happiness is both a building block for the quality of the living environment and at the same time it is shaped by it. This is what this post is about.

A municipality with residents who all feel happy. Who wouldn't want that? It is not an easily attainable goal, also because there are still many unanswered questions about the circumstances that make people happy.

In its broadest sense, happiness refers to people's satisfaction with their lives in general over an extended period.

Can happiness be developed?

Only in a limited way. According to Ruut Veenhoven, the Dutch 'happiness professor', half of happiness is determined by character traits, such as honesty, openness, optimism, forgiveness, and inquisiveness. Five societal characteristics determine the rest. These are a certain level of material wealth, social relations, health, living conditions and self-determination. In between, culture plays a role.

Happy and unhappy cities

What about the happiness of cities, for what it's worth? The happiness of cities depends on the self-declared degree of happiness (of a sample) of its inhabitants. Scandinavian cities dominate the top 10: Helsinki (Finland) and Aarhus (Denmark) rank first and second, Copenhagen (Denmark), Bergen (Norway) and Oslo (Norway) rank fifth, sixth and seventh. Stockholm (Sweden) is ninth. Amsterdam follows in 11th place. Two of the top ten cities are in Australia and New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand's capital, ranks third and Brisbane (Australia) ranks tenth. The only top ten cities not in the Scandinavia or Australia and New Zealand are Zurich (Switzerland) and Tel Aviv (Israel).

The bottom five cities are mainly cities that have been strongly marked by wars and conflicts: Kabul in Afghanistan, Sanaa in Yemen, Gaza in Palestine, and Juba in South Sudan. Delhi (India) ranks the fifth place from the bottom, because of the perceived very poor quality of life.

Independently from the place where they live, people who are happy are characterized by longevity, better health, more social relationships, and active citizenship.

Can cities improve their inhabitants’ happiness?

A happiness-based policy provides 'resources' in the first place, such as a livable income, affordable housing, health care and, in addition, creates circumstances ('conversion factors') to support people in making optimal use these resources. For instance, through social work, opportunities for participation, and invitation to festivities, such as street fairs, car-free days and music in the street.

Municipalities such as Schagen and Roerdalen consider the happiness of their citizens as the first goal for their policy. Cities abroad that intend the same are Bristol, Seoul, and Vilnius, among others. Nevertheless, Nancy Peters (project leader happiness of the municipality of Schagen) remarks: <em>We cannot make people happy. But the government offers a frame that helps people to become happy</em>.

Together with the Erasmus Happiness Economics Research Organization (EHERO), the municipality of Schagen has agreed on 12 spearheads: meaningful work, meaningful contact, participation in social life, connection with the neighbourhood, social safety net, trust in the municipality, pride in the place where people live, satisfaction with relationships, sports facilities, quality of public space, neighborhood-oriented cooperation and the relationship between citizens and community.

The importance of participation

In the previous blogposts, many topics have been discussed that easily fit in one of these spearheads. In his book <em>The Architecture of Happiness</em>, Alain de Botton notes that the characteristics of the environment that ignite social activities contribute most to the pursuit of happiness. In addition to the tangible properties of the living environment, participation by citizens plays is of importance as a direct consequence of self-determination.

25 years ago, residents of two streets in Portland (USA) decided to turn the intersection of those streets into a meeting place. At first, only tents, tables, chairs and play equipment were placed on the sidewalks, later the intersection itself was used at set times. After some negotiations, the city council agreed, if this would be sufficiently made visible. The residents didn't think twice and engaged in painting the street as visible as possible (See the image above). The residents agree that this whole project has made their lives happier and that the many activities they organize on the square still contribute to this.

The impact of happiness on the quality of the living environment.

But, what about the other way around, happiness as a building block for the quality of the living environment? Happy people are a blessing for the other inhabitants of a neighbourhood, because of their good mood, social attitude, willingness to take initiatives, and optimism regarding the future. At their turn, happy people can make most of available resources in their living environment because of the above-mentioned characteristics. Environmental qualities are not fixed entities: they derive their value from the meaning citizens give them. In this context, happiness is a mediator between environmental features and their appraisal by citizens.

Therefore, happy citizens can be found in Mumbai slums, and they might be happier than a selfish grumbler in a fancy apartment. At the same time, happy citizens might be best equipped to take the lead in collective action to improve the quality of the living environment, also because of the above-mentioned characteristics.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

24 Participation

This is the 24st episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Its topic is how involving citizens in policy, beyond the elected representatives, will strengthen democracy and enhance the quality of the living environment, as experienced by citizens.

Strengthening local democracy

Democratization is a decision-making process that identifies the will of the people after which government implements the results. Voting once every few years and subsequently letting an unpredictable coalition of parties make and implement policy is the leanest form of democracy. Democracy can be given more substance along two lines: (1) greater involvement of citizens in policy-making and (2) more autonomy in the performance of tasks. The photos above illustrate these lines; they show citizens who at some stage contribute to policy development, citizens who work on its implementation and citizens who celebrate a success.

Citizen Forums

In Swiss, the desire of citizens for greater involvement in political decision-making at all levels is substantiated by referenda. However, they lack the opportunity to exchange views, let alone to discuss them.

In his book Against Elections (2013), the Flemish political scientist David van Reybrouck proposes appointing representatives based on a weighted lottery. There are several examples in the Netherlands. In most cases, the acceptance of the results by the established politicians, in particular the elected representatives of the people, was the biggest hurdle. A committee led by Alex Brenninkmeijer, who has sadly passed away, has expressed a positive opinion about the role of citizen forums in climate policy in some advice to the House of Representatives. Last year, a mini-citizen's forum was held in Amsterdam, also chaired by Alex Brenninkmeijer, on the concrete question of how Amsterdam can accelerate the energy transition.

Autonomy

The ultimate step towards democratization is autonomy: Residents then not only decide, for example, about playgrounds in their neighbourhood, they also ensure that these are provided, sometimes with financial support from the municipality. The right to do so is formally laid down in the 'right to challenge'. For example, a group of residents proves that they can perform a municipal task better and cheaper themselves. This represents a significant step on the participation ladder from participation to co-creation.

Commons

In Italy, this process has boomed. The city of Bologna is a stronghold of urban commons. Citizens become designers, managers, and users of part of municipal tasks. Ranging from creating green areas, converting an empty house into affordable units for students, the elderly or migrants, operating a minibus service, cleaning and maintaining the city walls, redesigning parts of the public space etcetera.

From 2011 on commons can be given a formal status. In cooperation pacts the city council and the parties involved (informal groups, NGOs, schools, companies) lay down agreements about their activities, responsibilities, and power. Hundreds of pacts have been signed since the regulation was adopted. The city makes available what the citizens need - money, materials, housing, advice - and the citizens donate their time and skills.

From executing together to deciding together

The following types of commons can be distinguished:

Collaboration: Citizens perform projects in their living environment, such as the management of a communal (vegetable) garden, the management of tools to be used jointly, a neighborhood party. The social impact of this kind of activities is large.

Taking over (municipal) tasks: Citizens take care of collective facilities, such as a community center or they manage a previously closed swimming pool. In Bologna, residents have set up a music center in an empty factory with financial support from the municipality.

Cooperation: This refers to a (commercial) activity, for example a group of entrepreneurs who revive a street under their own responsibility.

Self-government: The municipality delegates several administrative and management tasks to the residents of a neighborhood after they have drawn up a plan, for example for the maintenance of green areas, taking care of shared facilities, the operation of minibus transport.

<em>Budgetting</em>: In a growing number of cities, citizens jointly develop proposals to spend part of the municipal budget.

The role of the municipality in local initiatives

The success of commons in Italy and elsewhere in the world – think of the Dutch energy cooperatives – is based on people’s desire to perform a task of mutual benefit together, but also on the availability of resources and support.

The way support is organized is an important success factor. The placemaking model, developed in the United Kingdom, can be applied on a large scale. In this model, small independent support teams at neighbourhood level have proven to be necessary and effective.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

AMS Conference: Final call for submissions & keynote speaker announcement

We're thrilled to share another round of exciting updates on the AMS Conference (April 23-24, 2024). As a quick reminder, the submission deadline has been extended to November 14th, providing you with an opportunity to be a contributor to this multi-dimensional event celebrating urban innovation and sustainability. Submit your abstract, workshop, or special session here 👉 https://reinventingthecity24.dryfta.com/call-for-abstracts

🎙️ Meet our keynote speaker: Charles Montgomery

We are honored to introduce Charles Montgomery, an award-winning author and urbanist, named one of the 100 most influential urbanists in the world by Planetizen magazine in 2023. Charles Montgomery leads transformative experiments, research, and interventions globally to enhance human well-being in cities.

His acclaimed book, Happy City, Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design, explores the intersection between urban design and the emerging science of happiness. His presentation at the AMS Conference, "Your city should be a trust machine," delves into the critical role of trust in human happiness and societal success. As the world grapples with a trust deficit, Charles Montgomery shares insights drawn from over a decade of using lessons from behavioral science and psychology to turn cities into better social machines.

🚀 Don't miss your chance to contribute to the future of cities! For more details about submissions and to submit your abstract, workshop, and/or special session, visit our conference website 👉 https://reinventingthecity24.dryfta.com/call-for-abstracts

Demoday #21: How to share the learnings of Local Energy Systems and form a coalition

When thinking about the decarbonization of cities, Local Energy Systems (LES) are often mentioned as one of the key enablers in the future. While there is agreement that LES have a role to play in the energy system of the future, what exactly is this role and how do we scale up implementation of this solution?

Cities are a major source of GHG emissions, with UN estimates suggesting that cities are responsible for ~75% of global emissions, mainly by means of transport and energy use in buildings. The decarbonization of buildings within urban areas can prove especially difficult, as space is limited, issues like grid congestion delay further electrification and there are a lot of stakeholders involved.

LES can be a solution in the decarbonisation of buildings in urban areas, like residential spaces, business parks and hybrid areas, creating positive energy districts that simultaneously reduce their impact on the grid. Preliminary LES pilot programs indicate that a LES can support decarbonization by integrating renewable generation and efficiently using energy by decreasing energy losses due to smart grids, communal energy management systems and by combining generation and use as locally as possible. We are however still in the early stages of building and growing LES around the globe, which is why we are focused on getting the right stakeholders together and learning about the requirements for scaling up such systems.

## Case & Set-up of the Session

During the latest Transition Day we hosted a work session on the topic of LES. In the past months, a number of partners in the Amsterdam Smart City network have expressed interest in the topic and would like to work together on the topic. Simultaneously the HvA, who is working on the ATELIER project with the aim to create Positive Energy Districts (PEDs), developed a framework to structurally categorize the various aspects involved in implemeting a LES. During the Demo Day, we considered two topics related to LES The first was a the framework created by the HvA, with the intention of capturing feedback and validating the approach. Secondly, we considered how we can move from an informal network around LES, to a structural coalition that can scale up the concept.

## Insights

A framework for structurally capturing aspects of a LES

Omar Shafqat from the HvA / ATELIer project presented their framework for structurally capturing and monitoring aspects of LES. The framework categorizes various aspects into policy, market, technical and social considerations (from top to bottom). Next to that, it divides these aspects on a timeline along a planning horizon from longer term (planning) to shorter term (management). The framework is shown below in this image.

In response to the framework, the participants shared some the following feedback:

- Testing the framework is necessary to validate and improve it. This implies an inventorization of LES projects and working through a few specific cases to check how the framework can be applied, and how it can benefit project managers/owners.

- The framework should also be presented and validated by other key stakeholders such as Amsterdam’s “Task Force Congestion Management”.

- Participants raised the question of who exactly will use the framework, and how? Is this intended as an instrument to be used primarily by academics, and researchers, or also by practitioners?

Forming a coalition on the advancement of LES

The second part of the work session was moderated by Joost Schouten from Royal Haskoning DHV, who led the discussion on the need for building a coalition around LES. He argued that the further development of LES requires an ecosystem approach, since multiple parties with different interests are involved, but there is no clear ‘owner’ of the problem.

A ‘coalition of the willing’ could help to advance the development of LES. A discussion in breakouts led to the following insights:

- A coalition should be formed by the community itself, but it requires a party that coordinates during the kick-off phase. A discussion emerged around whose role should be to take on the coordination phase. Some participants were of the view that this should be led by a governmental party, others thought this should be organised by a network party like Amsterdam Smart City.

- To effectively build a coalition, the involved parties need to be interdependent. To make sure that it is clear that the parties in a LES are interdependent, the parties need to state their interests in developing a LES, to determine whether there is a common goal.

- Even when these interests are not fully aligned, communication between parties can help bridge gaps. Discussion leads to understanding and empathy.

- An ambassador can be a vital enabler in the beginning of building a coalition, as a clear face and point of contact for such a group.

- There are already many other communities and coalitions working on topics related to LES, including but not limited to 02025, New Amsterdam Climate platform, TET-ORAM, TopSector Energie, among others. A key question is whether a new coalition is necessary, or whether it should be possible to join forces with an existing coalition / initiative.

## Conclusions and next steps

Many work session participants indicated support and interest to further contribute to the development of the LES project. The HvA framework was viewed as a useful tool to capture learnings from LES projects to facilitate scaling up. Additionally, the question of how to facilitate collaboration and coalition forming requires further attention. There are many parties involved in the development of LES, and they don’t always have the same interests. However, this is not an issue that any party can ‘own’ or ‘solve’ on its own. It requires an ecosystem approach, which is something that will need to be further detailed.

For now, we will simultaneously work on further building the coalition and looking for LES projects that can be used to test and further develop the framework. If you would like to know more or get involved in the project, for example by contributing you own LES to be tested by the framework itself, let me know via noor@amsterdamsmartycity.com.

This challenge was introduced in the Amsterdam Smart City network by Lennart Zwols from gemeente Amsterdam and Omar Shafqat (HvA). The session was prepared with and moderated by Joost Schouten from Royal HaskoningDHV. Do you have any questions or input for us? Contact me via noor@amsterdamsmartcity.com or leave a comment below. Would you like to know more about the LES challenge? You can find the overview of the challenge with the reports of all the sessions here.

16. A pleasant (family) home

This is the 16th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. This post is about one of the most important contributions to the quality of the living environment, a pleasant (family)home.

It is generally assumed that parents with children prefer a single-family home. New construction of this kind of dwelling units in urban areas will be limited due to the scarcity of land. Moreover, there are potentially enough ground-access homes in the Netherlands. Hundreds of thousands have been built in recent decades, while families with children, for whom this type of housing was intended, only use 25% of the available housing stock. In addition, many ground-access homes will become available in the coming years, if the elderly can move on to more suitable housing.

The stacked house of your dreams

It is expected that urban buildings will mainly be built in stacks. Stacked living in higher densities than is currently the case can contribute to the preservation of green space and create economic support for facilities at neighbourhood level. In view of the differing wishes of those who will be using stacked housing, a wide variation of the range is necessary. The main question that arises is what does a stacked house look like that is also attractive for families with children?

Area developer BPD (Bouwfonds Property Development) studied the housing needs of urban families based on desk research, surveys and group discussions with parents and children who already live in the city and formulated guidelines for the design of 'child-friendly' homes based on this.

Another source of ideas for attractive stacked construction was the competition to design the most child-friendly apartment in Rotterdam. The winning design would be realized. An analysis of the entries shows that flexible floor plans stand head and shoulders above other wishes. This wish was mentioned no less than 104×. Other remarkably common wishes are collective outdoor space [68×], each child their own place/play area [55×], bicycle shed [43×], roof garden [40×], vertical street [28×], peace and privacy [27× ], extra storage space [26×], excess [22×] and a spacious entrance [17×].

Flexible layout

One of the most expressed wishes is a flexible layout. Family circumstances change regularly and then residents want to be able to 'translate' to the layout without having to move. That is why a fixed 'wet unit' is often provided and wall and door systems as well as floor coverings are movable. It even happens that non-load-bearing partition walls between apartments can be moved.

Phased transition from public to private space

One of the objections to stacked living is the presence of anonymous spaces, such as galleries, stairwells, storerooms, and elevators. Sometimes children use these as a play area for lack of anything better. To put an end to this kind of no man's land, clusters of 10 – 15 residential units with a shared stairwell are created. This solution appeals to what Oscar Newman calls a defensible space, which mainly concerns social control, surveillance, territoriality, image, management, and sense of ownership. These 'neighborhoods' then form a transition zone between the own apartment, the rest of the building and the outside world, in which the residents feel familiar. Adults indicate that the use of shared cars should also be organized in these types of clusters.

Variation

Once, as the housing market becomes less overburdened, home seekers will have more options. These relate to the nature of the house (ground floor or stacked) and - related thereto - the price, the location (central or more peripheral) and the nature of the apartment itself. But also, on the presence of communal facilities in general and for children in particular.

Many families with children prefer that their neighbors are in the same phase of life and that the children are of a similar age. In addition, they prefer an apartment on the ground floor or lower floors that preferably consists of two floors.

Communal facilities

Communal facilities vary in nature and size. Such facilities contain much more than a stairwell, lift and bicycle storage. This includes washing and drying rooms, hobby rooms, opportunities for indoor and outdoor play, including a football cage on the roof and inner gardens. Houses intended for cohousing will also have a communal lounge area and even a catering facility.

However, the communal facilities lead to a considerable increase in costs. That is why motivated resident groups are looking for other solutions.

Building collectively or cooperatively

The need for new buildings will increasingly be met by cooperative or collective construction. Many municipalities encourage this, but these are complicated processes, the result of which is usually a home that better meets the needs at a relatively low price and where people have got to know the co-residents well in advance.

With cooperative construction, the intended residents own the entire building and rent a housing unit, which also makes this form of housing accessible to lower incomes. With collective building, there is an association of owners, and everyone owns their own apartment.

Indoor and outdoor space for each residential unit

Apartments must have sufficient indoor and outdoor space. The size of the interior space will differ depending on price, location and need and the nature of the shared facilities. If the latter are limited, it is usually assumed that 40 - 60 m2 for a single-person household, 60 - 100 m2 for two persons and 80 - 120 m2 for a three-person household. For each resident more about 15 to 20 m2 extra. Children over 8 have their own space. In addition, more and more requirements are being set for the presence, size, and safety of a balcony, preferably (partly) covered. The smallest children must be able to play there, and the family must be able to use it as a dining area. There must also be some protection against the wind.

Residents of family apartments also want their apartment to have a spacious hall, which can also be used as a play area, plenty of storage space and good sound insulation.

'The Babylon' in Rotterdam

De Babel is the winning entry of the competition mentioned before to design the ideal family-friendly stacked home (see title image). The building contains 24 family homes. All apartments are connected on the outside by stairs and wide galleries. As a result, there are opportunities for meeting and playing on all floors. The building is a kind of box construction that tapers from wide to narrow. The resulting terraces are a combination of communal and private spaces. Due to the stacked design, each house has its own shape and layout. The living areas vary between approximately 80 m2 and 155 m2 and a penthouse of 190 m2. Dimensions and layouts of the houses are flexible. Prices range from €400,000 – €1,145,000 including a parking space (price level 2021).

As promised, the building has now been completed, albeit in a considerably 'skimmed-down' form compared to the 'playful' design (left), no doubt for cost reasons. The enclosed stairs that were originally planned have been replaced by external steel structures that will not please everyone. Anyway, it is an attractive edifice.

13. Social safety