Stay in the know on all smart updates of your favorite topics.

Will the 15-minute city cause the US suburbs to disappear? 6/7

Urbanisation in the US is undergoing major changes. The image of a central city surrounded by sprawling suburbs therefore needs to be updated. The question is what place does the 15-minute city have in it? That is what this somewhat longer post is about

From the 1950s, residents of US cities began moving en masse to the suburbs. A detached house in the green came within reach for the middle and upper classes, and the car made it possible to commute daily to factories and offices. These were initially still located in and around the cities. The government stimulated this development by investing billions in the road network.

From the 1980s, offices also started to move away from the big cities. They moved to attractive locations, often near motorway junctions. Sometimes large shopping and entertainment centres also settled there, and flats were built on a small scale for supporting staff. Garreau called such cities 'edge cities'.

Investors built new suburbs called 'urban villages' in the vicinity of the new office locations, significantly reducing the distance to the offices. This did not reduce congestion on congested highways.

However, more and more younger workers had no desire to live in suburbs. The progressive board of Arlington, near Washington DC, took the decision in the 1980s to develop a total of seven walkable, inclusive, attractive and densely built-up cores in circles of up to 800 metres around metro stations. In each was a wide range of employment, flats, shops and other amenities . In the process, the Rosslyn-Balston Corridor emerged and experienced rapid growth. The population of the seven cores now stands at 71,000 out of a total of 136,000 jobs. 36% of all residents use the metro or bus for commuting, which is unprecedentedly high for the US. The Rosslyn-Balston Corridor is a model for many other medium-sized cities in the US, such as New Rochelle near new York.

Moreover, to meet the desire to live within walking distance of all daily amenities, there is a strong movement to also regenerate the suburbs themselves. This is done by building new centres in the suburbs and densifying part of the suburbs.

The new centres have a wide range of flats, shopping facilities, restaurants and entertainment centres. Dublin Bridge Park, 30 minutes from Columbus (Ohio) is one of many examples.

It is a walkable residential and commercial area and an easily accessible centre for residents from the surrounding suburbs. It is located on the site of a former mall.

Densification of the suburbs is necessary because of the high demand for (affordable) housing, but also to create sufficient support for the new centres.

Space is plentiful. In the suburbs, there are thousands of (semi-)detached houses that are too large for the mostly older couples who occupy them. An obvious solution is to split the houses, make them energy-positive and turn them into two or three starter homes. There are many examples how this can be done in a way that does not affect the identity of the suburbs (image).

New construction in suburbs

This kind of solution is difficult to realise because the municipal authorities concerned are bound by decades-old zoning plans, which prescribe in detail what can be built somewhere. Some of the residents fiercely oppose changing the laws. Especially in California, the NIMBYs (not in my backyard) and the YIMBYs (yes in my backyard) have a stranglehold on each other and housing construction is completely stalled.

But even without changing zoning laws, there are incremental changes. Here and there, for instance, garages, usually intended for two or three cars, are being converted into 'assessor flats' for grandma and grandpa or for children who cannot buy a house of their own. But garden houses are also being added and souterrains constructed. Along the path of gradualness, this adds thousands of housing units, without causing much fuss.

It is also worth noting that small, sometimes sleepy towns seem to be at the beginning of a period of boom. They are particularly popular with millennials. These towns are eminently 'walkable' , the houses are not expensive and there is a wide range of amenities. The distance to the city is long, but you can work well from home and that is increasingly the pattern. The pandemic and the homeworking it has initiated has greatly increased the popularity of this kind of residential location.

All in all, urbanisation in the US can be typified by the creation of giant metropolitan areas, across old municipal boundaries. These areas are a conglomeration of new cities, rivalling the old mostly shrinking and poverty-stricken cities in terms of amenities, and where much of employment is in offices and laboratories. In between are the suburbs, with a growing variety of housing. The aim is to create higher densities around railway stations. Besides the older suburbs, 'urban villages' have emerged in attractive locations. More and more suburbs are getting their own walkable centres, with a wide range of flats and facilities. Green space has been severely restricted by these developments.

According to Christopher Leinberger, professor of real estate and urban analysis at George Washington University, there is no doubt that in the US, walkable, attractive cores with a mixed population and a varied housing supply following the example of the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor are the future. In addition, walkable car-free neighbourhoods, with attractive housing and ample amenities are in high demand in the US. Some of the 'urban villages' are developing as such. The objection is that these are 'walkable islands', rising in an environment that is anything but walkable. So residents always have one or two cars in the car park for when they leave the neighbourhood, as good metro or train connections are scarce. Nor are these kinds of neighbourhoods paragons of a mixed population; rents tend to be well above the already unaffordable average.

The answer of the question in the header therefore is: locally and slowly

😀Resultaten - Is betrokkenheid van de gemeenschap de moeite waard? 😀

We hebben uiteenlopende en interessante reacties ontvangen van stedenbouwkundigen, architecten en gemeenten. Als u wilt weten wat andere professionals denken, vul dan deze enquête in met uw e-mailadres en wij delen de inzichten met u.

Bedankt! 😀

Follow Playground on LinkedIn

We've received varied and interesting responses from urban developers, architects, and municipalities. If you want to know what other professionals think, please fill out this survey with your email, and we will share the insights with you.

Thank you! 😀

The '15-minute principle' also applies to rural areas (4/7)

Due to a long stay in the hospital, I was unable to post my columns. I also cannot guarantee their continuity in the near future, but I will do my best...

In my previous post, I emphasised that urban densification should be coordinated with other claims on space. These are: expanding blue-green infrastructure and the desire to combine living and working. I am also thinking of urban horticulture. It is therefore unlikely that all the necessary housing in the Netherlands - mentioned is a number of one million housing units - can be realised in the existing built-up area. Expansion into rural areas is then inevitable and makes it possible to improve the quality of these rural areas. Densification of the many villages and small towns in our country enable to approach them from the '15-minute principle' as well. Villages should thereby become large enough to support at least a small supermarket, primary school and health centre, but also to accommodate small businesses. A fast and frequent public transport-connection to a city, to other villages and to a railway station in the vicinity is important.

A thorny issue is the quality of nature in the rural area. Unfortunately, it is in bad shape. A considerable part of the rural area consists of grass plots with large-scale agro-industrial use and arable land on which cattle feed is grown. Half of the Netherlands is for cows, which, incidentally, are mostly in stalls. Restoring nature in the area that is predominantly characterised by large-scale livestock farming, is an essential task for the coming decades.

The development of sufficiently dense built-up areas both in cities and villages and the development of new nature around and within those cities and villages is a beckoning prospect. This can be done by applying the idea of 'scheggen' in and around medium-sized and large cities. These are green zones that penetrate deep into the urban area. New residential and work locations can then join the already built-up area, preferably along existing railway lines and (fast) bus connections. These neighbourhoods can be built in their entirety with movement on foot and by bicycle as a starting point. The centre is a small densely built-up central part, where the desired amenities can be found.

In terms of nature development, depending on the possibilities of the soil, I am thinking of the development of forest and heath areas and lush grasslands, combined with extensive livestock farming, small-scale cultivation of agricultural and horticultural products for the benefit of nearby city, water features with a sponge function with partly recreational use, and a network of footpaths and cycle paths. Picture above: nature development and stream restoration (Photo: Bob Luijks)

Below you can link to my free downloadable e-book: 25 Building blocks to create better streets, neighborhoods and cities

How do higher density and better quality of life go together? 3/7

A certain degree of compactness is essential for the viability of 15-minute cities. This is due to the need for an economic threshold for facilities accessible by walking or cycling. A summary of 300 research projects by the OECD shows that compactness increases the efficiency of public services in all respects. But it also reveals disadvantages in terms of health and well-being due to pollution, traffic, and noise. The assumption is that there is an optimal density at which both pleasant living and the presence of everyday facilities - including schools - can be realised. At this point, 'densification' is not at the expense of quality of life but contributes to it. A lower density results in more car use and a higher density will reduce living and green space and the opportunity to create jobs.

The image above is a sketch of the 'Plan Papenvest' in Brussels. The density, 300 dwellings on an area of 1.13 hectares, is ten times that of an average neighbourhood. Urban planners often mention that the density of Dutch cities is much lower than in Paris and Barcelona, for example. Yet it is precisely in these cities that traffic is one of the main causes of air pollution, stress, and health problems. The benefits of compactness combined with a high quality of life can only be realised if the nuisances associated with increasing density are limited. This uncompromisingly means limiting car ownership and use.

Urban planners often seem to argue the other way round. They argue that building in the green areas around cities must be prevented at all costs to protect nature and that there is still enough space for building in the cities. The validity of this view is limited. In the first place, the scarce open space within cities can be better used for clean workshops and nature development in combination with water control. Secondly, much of the 'green' space outside cities is not valuable nature at all. Most of it is used to produce feed for livestock, especially cows. Using a few per cent of this space for housing does not harm nature at all. This housing must be concentrated near public transport. The worst idea is to add a road to the outskirts of every town and village. This will undoubtedly increase the use of cars.

Below you can link to my free downloadable e-book: 25 Building blocks to create better streets, neighborhoods and cities

Demoday #22: Data Commons Collective

In the big tech-dominated era, data has been commercially exploited for so long that it is now hard to imagine that data sharing might also benefit the community. Yet that is what a collective of businesses, governments, social institutions and residents in Amsterdam aim to do. Sharing more data to better care for the city. On behalf of the Data Commons Collective, Lia Hsu (Strategic Advisor at Amsterdam Economic Board) asked the Amsterdam Smart City network for input and feedback on their Data Commons initiative on the last Demoday of 2023.

What is a (data) common?

Commons are natural resources that are accessible to everyone within a community. Water. Fertile soil. Clean air. Actually everything the earth has given us. We as humanity have increasingly begun to exploit these commons in our pursuit of power and profit maximisation. As a result, we risk exhausting them.

Data is a new, digital resource: a valuable commodity that can be used to improve products and services. Data can thus also be used for the common good. However there are two important differences between a common and a data common: data in commons never runs out, and data in commons is not tied to any geographical location or sociocultural groups.

Four principles for Data Commons

The Data Commons collective is currently working on different applied use cases to understand how data commons can help with concrete solutions to pressing societal problems in the areas of energy, green urban development, mobility, health and culture. Each data commons serves a different purpose and requires a different implementation, but there are four principles that are always the same:

- The data common is used to serve a public or community purpose

- The data common requires cooperation between different parties, such as individuals, companies or public institutions

- The data common is managed according to principles that are acceptable to users and that define who may access the data commons under what conditions, in what ways they may be used, for what purpose, what is meant by data misuse

- The data common is embedded to manage data quality, but also to monitor compliance with the principles and ensure that data misuse is also noticed and that an appropriate response (such as a reprimand, penalty or fine) follows.

The Data Commons Collective is now in the process of developing a framework, which provides a self-assessment tool to guide the formation of Data Commons initiatives by triggering consideration of relevant aspects for creating a data commons. It is a means of reflection, rather than prescription, to encourage sustainable and responsible data initiatives.

Energy Data Commons case and Value Workshop by Waag

After the introduction to the Data Commons Collective and Framework by Simone van der Burg (Waag) and Roos de Jong (Deloitte), the participants engaged in a value workshop led by Simone. The case we worked with: we’re dealing with a shortage of affordable and clean energy. Congestion issues are only expected to get worse, due to increased energy use by households en businesses. An energy Data Commons in neighbourhoods can have certain benefits. Such as preventing congestion issues, using clean energy sources more effectively, becoming self-sufficient as a neighbourhood and reducing costs. But under what circumstances would we want to share our energy data with our neighbours? What are the values that we find important when it comes to sharing our energy data?

Results: Which values are important when sharing our energy data?

In smaller groups, the participants discussed which values they found important for an energy data common using a value card deck from Waag. Some values that were mentioned were:

- Trustworthiness: It is important to trust one another when sharing our energy data. It helps when we assume that everyone that is part of the common has the right intentions.

- Fun: The energy Data Commons should be fun and positive! The participants discussed gamification and rewards as part of the common.

- Knowledge: One of the goals of sharing data with each other is to gain more knowledge about energy consumption and saving.

- Justice and solidarity: If everyone in the common feels safe and acknowledged, it will benefit the outcome. Everyone in the common should be treated equally.

- Inclusion and Community-feeling: It is important that people feel involved in the project. The Data Commons should improve our lives, make it more sustainable but also progress our social relations.

During this Demoday, we got to know the Data Commons collective and experienced which values we find important when sharing our data with others. Amsterdam Economic Board will remain involved in the Data Commons Collective in a coordinating role and work on use cases to understand how data commons can work for society.

Would you like to know more about the Data Commons Collective or do you have any input for them? Please feel free to reach out to me via sophie@amsterdamsmartcity.com or leave a comment below.

The 15-minute city: from metaphor to planning concept (2/7)

Carlos Moreno, a professor at the Sorbonne University, helped Mayor Anne Hidalgo develop the idea of the 15-minute city. He said that six things made people happy: living, working, amenities, education, wellbeing, and recreation. The quality of the urban environment is enhanced when these functions are realized near each other. The monofunctional expansion of cities in the US, but also in the bidonvilles of Paris, is a thorn in his side, partly because this justifies owning a car.

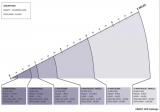

A more precise definition of the concept of the 15-minute city is needed before it can be implemented on a large scale. It is important to clarify which means of transport must be available to reach certain facilities in a given number of minutes. The list of facilities is usually very comprehensive, while the list of means of transport is usually only vaguely defined. But the distance you can travel in 15 minutes depends on the availability of certain modes of transport (see figure above).

Advocates of "new urbanism" have developed the tools to design 15-minute cities. They are based on three zones: the 5-minute walking zone, the 15-minute walking zone, which coincides with the 5-minute cycling zone, and finally the 15-minute cycling zone. These are not static concepts: In practice, the zones overlap and complement each other.

The 5-minute walking zone

This zone corresponds to the way in which most residential neighbourhoods functioned up until the 1960s, wherever you are in the world. Imagine a space with an average distance from the center to the edge of about 400 meters. In the center you will find a limited number of shops, a (small) supermarket, one or more cafes and a restaurant. The number of residents will vary between two and three thousand. Density will decrease from the centre and the main streets outwards. Green spaces, including a small neighbourhood park, will be distributed throughout the neighbourhood, as will workshops and offices.

In the case of new construction, it is essential that pedestrian areas have a dense network of paths without crossings at ground level with streets where car traffic is allowed. Some paths are wider and allow cycling within the 5- and 15-minute cycle zones. The streets provide access to concentrated parking facilities.

The 5-minute cycle zone and the 15-minute walking zone.

Here the distance from the center to the edge is about one kilometer. In this area, most of the facilities that residents need is available and can be distributed around the centers of the 5-minute walking zones. For example, a slightly larger supermarket may be located between two 5-minute walking zones. This zone will also contain one or more larger parks and some larger concentrations of employment.

This zone can be a large district of a city, but it can also be a small municipality or district of around 15 to 25,000 inhabitants. With such a population there will be little room for dogmatic design, especially when it comes to existing buildings. But even then, it is possible to separate traffic types by keeping cars off many streets and clustering car parks. The bottom line is that all destinations in this zone can be reached quickly by walking and cycling, and that car routes can be crossed safely.

The car will be used (occasionally) for several destinations. For example, for large shopping trips to the supermarket.

The 15-minute cycle zone.

This zone will be home to 100.00 or more residents. The large variation is due to the (accidental) presence of facilities for a larger catchment area, such as an industrial estate, a furniture boulevard or an IKEA, a university or a (regional) hospital. It is certainly not a sum of comparable 5-minute cycle zones. Nevertheless, the aim is to distribute functions over the whole area on as small a scale as possible. In practice, this zone is also crossed by several roads for car traffic. The network of cycle paths provides the most direct links between the 5-minute cycle zones and the wider area.

The main urban development objectives for this zone are good accessibility to urban facilities by public transport from all neighbourhoods, the prohibition of hypermarkets and a certain distribution of central functions throughout the area: Residents should be able to go out and have fun in a few places and not just in a central part of the city.

Below you can link to my free downloadable e-book: 25 Building blocks to create better streets, neighborhoods and cities.

Digitale tweeling als gesprekspartner in gebiedsontwikkeling

Zie digitale tweelingen niet als dé oplossing voor maatschappelijke vraagstukken die in gebieden spelen. Data en modellen belichten namelijk slechts een deel van de werkelijkheid. Bij ruimtelijke opgaven, zoals het woningtekort, de energietransitie en natuurherstel, gaat het om het gesprek om te komen tot een gedeelde werkelijkheid. Zorg dat digitalisering hierbij een constructieve rol speelt.

Op de grens van Brabant en Limburg ligt de Peel. Daar komen onder grote tijdsdruk verschillende opgaven samen: transitie van de landbouw, omslag naar hernieuwbare energie inclusief netverzwaringen, woningtekort, verdroging van de Peel en de mogelijke heropening van de vliegbasis Vredepeel. Het maken van die ruimtelijke puzzel vergt samenwerking tussen twintig gemeenten, drie waterschappen, twee provincies, diverse departementen en tal van bedrijven, maatschappelijke organisaties en burgers. Daarnaast vraagt die puzzel een integrale afweging: ingrepen voor de ene opgave kunnen immers vergaande gevolgen hebben voor andere opgaven.

Voor de digitale tweeling is echter geen vraagstuk te complex, schreef Microsoft in een artikel op Ibestuur. Het bedrijf werkt zelfs aan een digitale tweeling van de aarde, met de ambitie om deze beter te besturen voor mens en natuur. Tijdens een conferentie over slimme steden in Barcelona viel de sterke aantrekkingskracht van de digitale tweeling voor beleidsmakers en bestuurders op. ‘Doe mij ook maar zo’n digitale tweeling’ leek de dominante gedachte te zijn. De talrijke pilots en experimenten met digitale tweelingen in het ruimtelijk domein onderstrepen dit.

Hype?

Er lijkt sprake van een ‘hype’: digitale tweelingen als panacee voor gebiedsontwikkeling. Deze ‘hype’ hangt samen met de toenemende hoeveelheid en beschikbaarheid van (real-time) data over onze leefomgeving, zoals lucht-, grond- en waterkwaliteit en energieverbruik. Dit is mede het gevolg van het beter en goedkoper worden van monitoringstechnieken, zoals slimme meters in huis en allerlei soorten sensoren op straat, in drones en satellieten. Daarnaast stimuleert en verplicht de aankomende Omgevingswet het gebruik van data.

Partijen gebruiken verschillende definities voor de digitale tweeling. Doorgaans verwijst de term ‘digitale tweeling’ naar het idee dat een fysieke en virtuele ‘tweeling’ met elkaar in verbinding staan door de uitwisseling van data en informatie. Data over de fysieke wereld voeden de virtuele tweeling en inzichten daaruit kunnen weer worden gebruikt om te interveniëren in de fysieke wereld. Dat helpt bij het maken van allerlei producten – van de bouw van de Boekelose brug tot de BMW fabriek – en het verbeteren van bedrijfsprocessen, zoals het onderhoud en beperking van de CO2-uitstoot van de Airbus.

Hierdoor geïnspireerd, zien veel beleidsmakers en bestuurders de digitale tweeling als een belangrijk middel om besluitvorming – van beleidsvoorbereiding tot implementatie – te verbeteren door de gevolgen van keuzes te simuleren en te visualiseren. In het domein van politiek en bestuur is de digitale tweeling dus meer dan een technologische innovatie; het is een democratische innovatie. Dit roept de vraag op: hoe kan een digitale tweeling de besluitvorming daadwerkelijk verbeteren?

Er bestaat geen eenduidige werkelijkheid

Dat kan door de variëteit en veelzijdigheid van een gebied te erkennen. Een gebied is nooit één monolithische werkelijkheid; er spelen vaak duizend-en-een belangen en processen tegelijk. Toch is zo’n eenduidige werkelijkheid wel precies wat een digitale tweeling suggereert. En daarin schuilt zowel de kracht als het risico van dit instrument. Kracht, omdat het zorgt voor een basis voor een gesprek. En een goed gesprek is de basis voor goede besluitvorming. Risico, omdat zo’n eenduidige werkelijkheid ons kan doen vergeten dat de digitale tweeling selectief is. Hij laat slechts een beperkt aantal variabelen zien. Bovendien, datgene wat subjectief of lastiger meetbaar is, bijvoorbeeld de betekenis van een gebied voor haar inwoners, kunnen we gemakkelijk over het hoofd zien. Terwijl een democratisch proces juist ook voor die zachte waarden aandacht behoort te hebben.

Gesprekspartner

Beschouw een digitale tweeling dus niet als de gedeelde werkelijkheid zelf, maar als gesprekspartner in een breder democratisch proces. Daarbij is ook transparantie van belang over welke data wel aanwezig zijn en welke niet. En over welke modellen gebruikt worden en de aannames die daarbij gemaakt worden. Zo laat de maatschappelijke aandacht voor bijvoorbeeld de stikstofmodellen van het RIVM zien dat data en modellen niet neutraal zijn en ook niet apolitiek, ook al worden ze soms wel zo gepresenteerd. Data, modellen en algoritmes hebben namelijk invloed op hoe we problemen definiëren en begrijpen, wie daarbij betrokken worden en hoe we vervolgens handelen. Of toegepast op besluitvorming: ze bepalen welke maatschappelijke opgaven wel en niet worden opgepakt en hoe en wie wel of niet mee mag praten en beslissen.

Praktijkcases?

Dit artikel is een weergave van een aantal eerste inzichten in een project van het Rathenau Instituut naar de wijze waarop digitale tweelingen kunnen bijdragen aan besluitvorming over gebiedsontwikkeling. Hierin heeft het Rathenau samengewerkt met de Provincie Noord-Holland. Voor het vervolg van dit project is het instituut op zoek naar interessante praktijkcases.

De digitale tweeling als gesprekspartner dus. Hoe doe je dat op een verantwoorde manier? Wie kan hier praktijkcases van laten zien?

Dit artikel is geschreven door Romy Dekker (Rathenau Instituut), Paul Strijp (Provincie Noord-Holland) Allerd Nanninga (Rathenau Instituut) en Rinie van Est (Rathenau Instituut) en gepubliceerd op iBestuur. De auteurs danken Brian de Vogel, Henk Scholten, Arny Plomp, Herman Wilken, Rosemarie Mijlhoff, Jan Bruijn en Martine Verweij voor hun waardevolle inbreng in het project.

Beeld: Shutterstock

11. Nature inclusivity

This is the 11th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. In this post, I wonder whether nature itself can tackle the environmental problems that humans have caused.

Ecosystem services

According to environmental scientists, ecosystems are providers of services. They are divided into production services (such as clean drinking water, wood, and biomass), regulating services (such as pollination, soil fertility, water storage, cooling, and stress reduction) and cultural services (such as recreation, and natural beauty). In case of nature-inclusive solutions ecosystems are co-managed to restore the quality of life on the earth in the short term and to maintain it in the long term, insofar as that is still possible.

The green-blue infrastructure

The meaning of urban green can best be seen in conjunction with that of water, hence the term green-blue infrastructure. Its importance is at least fourfold: (1) it is the source of all life, (2) it contributes substantially to the capture and storage of CO2, (3) 'green' has a positive impact on well-being and health; (4) it improves water management. This post is mainly about the third aspect. The fourth will be discussed in the next post. 'Green' has many forms, from sidewalk gardens to trees in the street or vegetated facades to small and large parks (see collage above).

Improving air quality

Trees and plants help to filter the water itself. They have a significant role to play in managing water and air pollution. Conifers capture particulate matter. However, the extent to which this occurs is less than is necessary to have a significant impact on health. Particulate matter contributes to a wide range of ailments. Like infections of the respiratory system and cardiovascular disease, but also cancer and possibly diabetes.

Countering heat stress

Heat stress arises because of high temperature and humidity. The wind speed and the radiation temperature also play a role. When the crowns of trees cover 20% of the surface of an area, the air temperature decreases by 0.3oC during the day. However, this relatively small decrease already leads to a 10% reduction in deaths. Often 40% crown area over a larger area is considered as an optimum.

Reduce mental stress and improve mood

According to Arbo Nederland, 21% of the number of absenteeism days is stress-related, which means approximately a €3 billion damage. A short-term effect of contact with nature on stress, concentration and internal tranquility has been conclusively demonstrated. The impact of distributing greenery within the residential environment is larger than a concentrated facility, such as a park, has.

Strengthening immune function via microbiome

The total amount of greenery in and around the house influences the nature and quantity of the bacteria present. This green would have a positive effect on the intestinal flora of those who are in its vicinity and therefore also on their immune function. The empirical support for this mechanism is still rather limited.

Stimulate physical activity

The impact of physical activity on health has been widely demonstrated. The Health Council therefore advises adults to exercise at least 2½ hours a week. The presence of a green area of at least ¼ hectare at 300 meters from the home is resulting more physical activity of adults in such areas, but not to more activity as a whole.

Promoting social contact

Well-designed green areas near the living environment invite social contacts. For instance, placement of benches, overview of the surroundings and absence of traffic noise. The state of maintenance are important: people tend to avoid neglected and polluted areas of public space, no matter how green.

Noise reduction

Vegetation dampens noise to some extent, but it is more important that residents of houses with a green environment experience noise as less of a nuisance. It is assumed that this is due to a mechanism already discussed, namely the improvement of stress resistance because of the greenery present.

Biophilic construction

For years buildings made people sic. A growing number of architects want to enhance the effect of 'green' on human health by integrating it into the design of houses and buildings and the materials used. This is the case if it is ensured that trees and plants can be observed permanently. But also, analogies with natural forms in the design of a building

The 'Zandkasteel', the former headquarters of the Nederlandse Middenstandsbank in Amsterdam, designed by the architects Ton Alberts and Max van Huut, is organically designed both inside and outside, inspired by the anthroposophical ideas of Rudolf Steiner. The (internal) water features are storage for rainwater and the climate control is completely natural. The building has been repurposed for apartments, offices and restaurants.

Green gentrification

Worldwide, there is a direct correlation between the amount of greenery in a neighborhood and the income of its residents. Conversely, we see that poorer neighborhoods where new green elements are added fall victim to green gentrification over time and that wealthier housing seekers displace the original residents.

The challenge facing city councils is to develop green and fair districts where gentrification is halted and where poorer residents can stay. Greening in poor communities must therefore be accompanied by measures that respect the residential rights and aim at improving the socio-economic position of the residents.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

10. Health

Most important causes of death worldwide (Source: The Lancelet, le Monde)

This is the 10th episode of a series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. In this post, I mainly focus on health problems which are directly related to the quality of the living environment

Are cities healthy places?

According to the WHO's Global Burden of Diseases Study, 4.2 million deaths worldwide each year are caused by particulate matter. The regional differences are significant. Urban health depends on the part of the world and the part of the city where you are living. More than 26 million people in the United States have asthma and breathing problems as a result. African-American residents in the US die of asthma three times as often as whites. They live in segregated communities with poor housing, close to heavy industry, transportation centers and other sources of air pollution.

Globally, the increasing prosperity of city dwellers is causing more and more lifestyle-related health problems. Heart disease, and violence (often drug-related) has overtaken infectious diseases as the first cause of death in wealthy parts of the world.

The Netherlands

Very recently, Arcadis published a report on 'the healthy city'. This report compares 20 Dutch cities based on many criteria, divided over five domains. The four major cities score negatively on many aspects. In particular: healthy outdoor space, greenery, air quality, noise nuisance, heat stress and safety. Medium-sized cities such as Groningen, Emmen, Almere, Amersfoort, Nijmegen, and Apeldoorn, on the other hand, are among the healthiest cities.

In Amsterdam, the level of particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) in 2018 exceeded World Health Organization standards in many streets. The GGD of Amsterdam estimates that 4.5% of the loss of healthy years is the result of exposure to dirty air.

Collaborative measuring air quality

In various cities, groups of concerned citizens have started measuring the quality of the air themselves. A professional example is the AiREAS project in Eindhoven. An innovative measuring system has been developed together with knowledge institutions and the government. Sensors are distributed over the area of the city and the system provides real-time information. The AiREAS group regularly discusses the results with other citizens and with the city government. The measurement of the quality of the air is supplemented by medical examination. This research has confirmed that citizens in the vicinity of the main roads and the airport have an increased risk of mortality, reduced lung function and asthma.

The AiREAS project is linked to similar initiatives in other European cities. Occasionally the data is exchanged. That resulted in, among other things, this shocking video.

Future?

Could the future not be that we are busy doing the obvious things for our health, such as walking, cycling, eating good food and having fun and that thanks to wearables, symptoms of diseases are watched early and permanently in the background, without us being aware of it? The local health center will monitor and analyze the data of all patients using artificial intelligence and advise to consult the doctor if necessary. An easily accessible health center in one's own neighborhood remains indispensable.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

5. Integration of high-rises

This article is part of the series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Read how the design of high-rises might comply with the quality of the urban environment.

High-rises are under scrutiny in two respects. First, its necessity or desirability. Secondly, their integration in the urban fabric. This post is about the latter.

Options for high-rises

Suppose you want to achieve a density of 200 housing equivalents in a newly to build area of one hectare. A first option is the way in which Paris and Barcelona have been built: Contiguous buildings from five to eight floors along the streets, with attractive plinths. In addition, or as an addition, others prefer high-rises because of their capacity of enhancing the metropolitan appearance of the area. Not to increase the density in the first place.

Integrative solution

Almost all urban planners who opt for the latter option take as starting point rectangular blocks, which height along the streets is limited to 4-6 storeys, including attractive plinths. The high-rise will then be realized backwards, to keep its massiveness out of sight. The image at top left gives an impression of the reduced visibility of high-rises at street level on Amsterdam's Sluisbuurt. According to many, this is a successful example of the integration of high-rises, just like the Schinkelkwartier under development, also in Amsterdam(picture top right).

Separate towers

The last option is also recognisable in all urban plans with a metropolitan character in Utrecht and Rotterdamand more or less in The Hague too. This represents a turnaround from the past. Research by Marlies de Nijsshowed that only 20% of all high-rises built before 2015 met this condition. These buildings consist of separate towers without an attractive plinth. What you see at ground floor-level are blank walls hiding technical, storage or parking areas. The Zalmtoren in Rotterdam, the tallest building in the Netherlands, exemplifies this (picture below right). This kind of edifices is mostly surrounded by a relatively large space of limited use. Other disadvantages of detached high-rises are the contrast with adjacent buildings, their windy environment, the intense shadows, its ecological footprint, and the costs.

Paris

Two extreme examples of disproportionate high-rises can be found in Paris. Paris has always applied a limitation of the building height to 37 meters within the zone of the Périférique. The exception is the Eiffel Tower, but it was only meant to be temporary. In the two short periods that this provision was cancelled, two buildings have risen: The first is the 210-meter-high Tour Montparnasse, which most Parisians would like to demolish immediately. Instead, the building will be renovated at a cost of €300 million in preparation for the Olympic Games. After 10 years of struggle, construction of the second has started in 2021. It is the 180-meter-high Tour Triangle, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, so-called star architects. The photos at the bottom left and centre show the consequences for the cityscape.

Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/x39qvzkw687rxsjvhsrzn/overzicht-blogposts-Eng.docx?rlkey=vpf7pwlfxkildpr9r062t5gf2&dl=0

2. Human density

This article is part of the series 25 building blocks to create better streets, neighbourhoods, and cities. Read how design, departing from the human dimension contributes to the quality of the urban environment. Follow the link below to find an overview of all articles.

Human dimension means that residents nor visitors feel overwhelmed by the environment. An urban planner must avoid them thinking that it is all about other things, such as commerce, traffic, or the buildings themselves, which unfortunately often is the case indeed. Constructions by 'star architects' can be crowd pullers but usually also result into a disproportionate use of space. Cities therefore better tolerate only a limited number of such edifices. Alexander Herrebout (OTO Landscape) believes that space has a human dimension if you experience attention for you as a human being and that there are objects you can connect with. For many, this will be more often a historic building (church, town hall) than a modernist one.

Compactness (‘enclosure’)

Compact streets and squares give a sense of security. They encourage people to linger there, increasing the chance of unforeseen encounters. Sjoerd Soeters considers squares in the first place as a widening in the street pattern and therefore they are preferably no larger than 24 by 40 meters. A round or oval shape enhances the feeling of security. If the height of the surrounding buildings is also in line with this, there may be contact between residents and people on the street. Good examples are the square he designed in the Oostpoort shopping center in Amsterdam, but also a square in <em>The Point</em>, a new shopping center in Utah (US), resp. bottom left and bottom center and of course the Piazza der Campo in Siena.

If streets are too wide or narrow or buildings are too high?

Trees, for example a double row all around, will help if a street is too wide or a square is too big. Trees are also a source of reducing urban heat. The extent to which trees contribute to the sense of intimacy is expressed by comparing the images at the top left (Herring Cove Road, Halifax, Canada) and the top right (Course Mirabeau, Aix-en-Provence). A square or a street that is too wide can be further visually reduced by the construction of terraces, the placement of a pavilion or the presence of water features, such as on the Brusselplein, Leidsche Rijn (bottom right). Sometimes also by allowing destination traffic and public transport.

A street that is too narrow can be widened psychologically by designing sidewalks and a carriageway in the same level and shades, possibly separated by a narrow band, as illustrated in the image of the Sluisbuurt in Amsterdam (top center).

If case of high-rises, the human dimension can be respected by planting trees and by placing taller buildings back from the plinth to limit their visibility from the street. This is also illustrated by the image of the Sluisbuurt (top center).

Density

Compactness presupposes a certain density. In a very dense city center is only room for pedestrians and not for traffic, in some cases except for the tram. Though, these areas must be always accessible to emergency services. Waste removal, deliveries and parking must be solved differently, for example on the inner space of blocks or by introducing strict time slots. Every city also needs space for events such as concerts, fairs, etcetera. Accessibility is more important than a central location.

Transition Day 2023: Digital identity and implementing new electronic identification methods

The Digital Government Act (Wet Digitale Overheid) aims to improve digital government services while ensuring citizens' privacy. An important part of this law is safe and secure logging in to the government using new electronic identification methods (eIDs) such as Yivi (formerly IRMA). The municipality of Amsterdam recently started a pilot with Yivi. Amsterdam residents can now log in to “Mijn Amsterdam” to track the status of complaints about public area’s. But how do you get this innovation, which really requires a different way of thinking, implemented?

Using the Change Curve to categorise barriers

At the Transition day (June 2023), Mike Alders (municipality of Amsterdam) invited the Amsterdam Smart City network to help identify the barriers and possible interventions, and explore opportunities for regional cooperation. Led by Coen Smit from Royal HaskoningDHV, the participants identified barriers in implementing this new technology from an organisational and civil society perspective. After that, the participants placed these barriers on a Change Curve, a powerful model used to understand the stages of personal transition and organization stage. Using the Change Curve, we wanted to give Mike some concrete guidance on where to focus his interventions on within the organisation. The barriers were categorised in four phases:

- Awareness: associated with anxiety and denial;

- Desire: associated with emotion and fear;

- Knowledge & ability: associated with acceptance, realisation and energy;

- Reinforcement: associated with growth.

Insights and next steps

In the case of digital identity and the implementation of eID’s, such as Yivi, it appears that most of the barriers are related to the first phase of awareness. Think of: little knowledge about digital identity and current privacy risks, and a lack of trust in a new technology. Communication is crucial to overcome barriers in the awareness. To the user, but also internally to employees and the management. Directors often also know too little about the topic of digital identity.

By looking at the different phases in the change process, we have become aware of the obstacles and thought about possible solutions. But we are still a long way from full implementation and acceptance of this new innovation. For that, we need different perspectives from business, governments and knowledge institutions. This way, we can start creating more awareness about digital transformations and identity in general, which will most likely lead to wishes for more privacy-friendly and easier way of identifying online. Besides focusing on creating more awareness about our digital identity, another possible next step is to organise a more in-depth session (deepdive) with all governmental organisations in the Amsterdam Smart City network.

Do you have any tips or questions in relation to Mike’s project about Digital Identity and electronic Identification? Please get in touch with me through sophie@amsterdamsmartcity.com or leave a comment below.

Demoday #19: CommuniCity worksession

Without a doubt, our lives are becoming increasingly dependent on new technologies. However, we are also becoming increasingly aware that not everyone benefits equally from the opportunities and possibilities of digitization. Technology is often developed for the masses, leaving more vulnerable groups behind. Through the European-funded CommuniCity project, the municipality of Amsterdam aims to support the development of digital solutions for all by connecting tech organisations to the needs of vulnerable communities. The project will develop a citizen-centred co-creation and co-learning process supporting the cities of Amsterdam, Helsinki, and Porto in launching 100 tech pilots addressing the needs of their communities.

Besides the open call for tech-for-good pilots, the municipality of Amsterdam is also looking for a more structural process for matching the needs of citizens to solutions of tech providers. During this work session, Neeltje Pavicic (municipality of Amsterdam) invited the Amsterdam Smart City network to explore current bottlenecks and potential solutions and next steps.

Process & questions

Neeltje introduced the project using two examples of technology developed specifically for marginalised communities: the Be My Eyes app connects people needing sighted support with volunteers giving virtual assistance through a live video call, and the FLOo Robot supports parents with mild intellectual disabilities by stimulating the interaction between parents and the child.

The diversity of the Amsterdam Smart City network was reflected in the CommuniCity worksession, with participants from governments, businesses and knowledge institutions. Neeltje was curious to the perspectives of the public and private sector, which is why the group was separated based on this criteria. First, the participants identified the bottlenecks: what problems do we face when developing tech solutions for and with marginalised communities? After that, we looked at the potential solutions and the next steps.

Bottlenecks for developing tech for vulnerable communities

The group with companies agreed that technology itself can do a lot, but that it is often difficult to know what is already developed in terms of tech-for-good. Going from a pilot or concept to a concrete realization is often difficult due to the stakeholder landscape and siloed institutions. One of the main bottlenecks is that there is no clear incentive for commercial parties to focus on vulnerable groups. Another bottleneck is that we need to focus on awareness; technology often targets the masses and not marginalized groups who need to be better involved in the design of solutions.

In the group with public organisations, participants discussed that the needs of marginalised communities should be very clear. We should stay away from formulating these needs for people. Therefore, it’s important that civic society organisations identify issues and needs with the target groups, and collaborate with tech-parties that can deliver solutions. Another bottleneck is that there is not enough capital from public partners. There are already many pilots, but scaling up is often difficult.. Therefore solutions should have a business, or a value-case.

Potential next steps

What could be the next steps? The participants indicated that there are already a lot of tech-driven projects and initiatives developed to support vulnerable groups. A key challenge is that these initiatives are fragmented and remain small-scale because there is insufficient sharing and learning between them. A better overview of what is already happening is needed to avoid re-inviting the wheel. There are already several platforms to share these types of initiatives but they do not seem to meet the needs in terms of making visible tested solutions with most potential for upscaling. Participants also suggested hosting knowledge sessions to present examples and lessons-learned from tech-for-good solutions, and train developers to make technology accessible from the start. Legislation can also play a role: by law, technology must meet accessibility requirements and such laws can be extended to protect vulnerable groups. Participants agreed that public authorities and commercial parties should engage in more conversation about this topic.

In response to the worksession, Neeltje mentioned that she gained interesting insights from different angles. She was happy that so many participants showed interest in this topic and decided to join the session. In the coming weeks, Neeltje will organise a few follow-up sessions with different stakeholders. Do you have any input for her? You can contact me via sophie@amsterdamsmartcity.com, and I'll connect you to Neeltje.

Beep for Help, direct hulp aan huis

Beep for help ontzorgt alle Amsterdammers die wel wat hulp thuis kunnen gebruiken.

De oplossing voor ouderen die prettig thuis willen blijven wonen, overbelaste mantelzorgers of mensen die meer tijd willen voor ontspanning.

Makkelijk boeken van hulp bij boodschappen, koken, schoonmaken, tuinieren, huisdieren of gezelschap. Zonder wachtlijsten. Simpel en snel. Wij zijn er trots op een Amsterdamse startup te zijn. Wij werken graag samen met andere organisaties om elkaar te versterken. Neem contact op voor de mogelijkheden.

The Public Stack: a Model to Incorporate Public Values in Technology

Public administrators, public tech developers, and public service providers face the same challenge: How to develop and use technology in accordance with public values like openness, fairness, and inclusivity? The question is urgent as we continue to rely upon proprietary technology that is developed within a surveillance capitalist context and is incompatible with the goals and missions of our democratic institutions. This problem has been a driving force behind the development of the public stack, a conceptual model developed by Waag through ACROSS and other projects, which roots technical development in public values.

The idea behind the public stack is simple: There are unseen layers behind the technology we use, including hardware, software, design processes, and business models. All of these layers affect the relationship between people and technology – as consumers, subjects, or (as the public stack model advocates) citizens and human beings in a democratic society. The public stack challenges developers, funders, and other stakeholders to develop technology based on shared public values by utilising participatory design processes and open technology. The goal is to position people and the planet as democratic agents; and as more equal stakeholders in deciding how technology is developed and implemented.

ACROSS is a Horizon2020 European project that develops open source resources to protect digital identity and personal data across European borders. In this context, Waag is developing the public stack model into a service design approach – a resource to help others reflect upon and improve the extent to which their own ‘stack’ is reflective of public values. In late 2022, Waag developed a method using the public stack as a lens to prompt reflection amongst developers. A more extensive public stack reflection process is now underway in ACROSS; resources to guide other developers through this same process will be made available later in 2023.

The public stack is a useful model for anyone involved in technology, whether as a developer, funder, active, or even passive user. In the case of ACROSS, its adoption helped project partners to implement decentralised privacy-by-design technology based on values like privacy and user control. The model lends itself to be applied just as well in other use cases:

- Municipalities can use the public stack to maintain democratic approaches to technology development and adoption in cities.

- Developers of both public and private tech can use the public stack to reflect on which values are embedded in their technology.

- Researchers can use the public stack as a way to ethically assess technology.

- Policymakers can use the public stack as a way to understand, communicate, and shape the context in which technology development and implementation occurs.

Are you interested in using the public stack in your own project, initiative, or development process? We’d love to hear about it. Let us know more by emailing us at publicstack@waag.org.

'Better cities' is nu 'Steden en digitalisering'

Vorige week heb ik de community geattendeerd op de publicatie van mijn e-book Better cities and digitization. Dat is een compilatie van de 23 posts op deze website het afgelopen half jaar.

Inmiddels is ook de Nederlandstalige versie Steden en digitalisering beschikbaar. Ik sta daarin eerst stil bij de technocentrische en de mensgerichte benadering van smart cities. Daarna problematiseer ik de roep om 'datagestuurd beleid'. Ik ga vervolgens uitvoerig in op ethische principes bij de beoordeling van technologieën. Vervolgens beschrijf ik een procedure hoe steden met digitalisering zouden kunnen omgaan, te beginnen met Kate Raworth. Ook het digitaliseringsbeleid van Amsterdam krijgt aandacht. Daarna komen vier toepassingen aan de orde: bestuur, energie, mobiliteit en gezondheidszorg. Wie doorleest tot op de laatste bladzijde ziet dat Amsterdam Smart City het laatste woord krijgt;-)

Via de link hieronder kun je dit boek gratis downloaden.

Rapport 'Beter beslissen over datacentra' (Rathenau Instituut)

In de afgelopen maanden is de maatschappelijke en politieke discussie over de vestiging van datacentra in een stroomversnelling geraakt. Naar aanleiding van de plannen voor de bouw van een groot datacentrum bij Zeewolde is veel gesproken over nut, noodzaak en wenselijkheid van vestiging van dit soort faciliteiten in Nederland. Daarbij kwamen zorgen naar boven over de verhouding tussen het energie- en grondstoffengebruik van datacentra en hun maatschappelijke en economische meerwaarde. Ook was er kritiek op hoe de besluitvorming over de vestiging van datacentra bestuurlijk is ingericht.

Het rapport 'Beter beslissen over datacentra' van het Rathenau Instituut onderzoekt de maatschappelijke betekenis van datacentra en de besluitvorming over hun vestiging. Het maakt inzichtelijk wat datacentra zijn, hoe ze werken en hoe ze onderling van elkaar verschillen, welke kwesties er spelen en hoe deze kwesties op dit moment bestuurd worden op lokaal, regionaal en nationaal niveau. De analyse mondt uit in vijf aanbevelingen voor een goede publieke governance van de digitale infrastructuur.

Het Rathenau Instituut pleit ervoor om bij de ontwikkeling van beleid, niet te focussen op de (grote) datacentra die nu volop in de belangstelling staan, maar te kijken naar de hele infrastructuur die de digitalisering van onze samenleving mogelijk maakt. Daarbij gaat het ook om kabels, zendmasten, ontvangers, schakelaars en routers, plus de functies die zij in samenhang vervullen. Wat willen we in Nederland met deze infrastructuur? Die vraag zou het voorwerp moeten zijn van een maatschappelijk debat. Naast bestuurders en deskundigen, moeten ook burgers daarbij betrokken zijn. Om het debat te voeden, is ook meer kennis nodig, bijvoorbeeld over de financieel-economische voordelen van datacentra.

De digitale infrastructuur is inmiddels zo belangrijk geworden voor de samenleving dat ze kenmerken heeft van een nutsvoorziening: een essentiële voorziening van algemeen belang. Dit betekent dat publieke waarden leidend moeten zijn bij de governance van deze infrastructuur. Het bestaande energiebeleid kan daartoe als model dienen. Het onderzoek laat zien dat relevante publieke waarden voor de digitale infrastructuur, veel gelijkenis vertonen met de waarden die ten grondslag liggen aan het Nederlandse energiebeleid. Ook hier immers gaat het om betrouwbaarheid, veiligheid, betaalbaarheid, duurzaamheid en goede ruimtelijke inpassing.

Meer hierover kunt u lezen op https://www.rathenau.nl/nl/digitale-samenleving/beter-beslissen-over-datacentra.

Foto bij bericht: Shutterstock

The Creative Industry Program's

The Creative Industry Program's main objective is to enhance creative skills in all segments of the industry, stimulating the emergence of new business opportunities, in addition to offering business representation, professional education and technology for various creative sectors.

The Program works in the development of industries through forums, and through the articulation of a network that includes universities, development agencies, government and private initiative, and creative networks. Internationally, the Creative Industry Program is a reference for countries and international organizations.

Based on the needs and opportunities identified in the economic context, the Program works to develop innovative skills, in order to create a favorable environment for business.

The Creative Industry Program seeks to develop the potential of creative entrepreneurship networks, in addition to promoting distribution through communication channels.

to know more

Send us an email to motivaco@gmail.com

We can navigate wickedness together

On the 25 and 26st of November the Amsterdam Smart City network worked together to tackle big wicked problems that exist in the region. But is it even possible to tackle wicked problems? In a masterclass on the first day, initiated by the ASC wicked problems team, Marije Poel (HvA) and Nora van der Linden (Kennisland) tried to change the perspective: what if we aim to navigate wickedness together?

While we work on big and complex issues like the energy transition or the digital transition, we try to get a grip on problems and come up with a structured plan or linear project. But that approach is not always in line with reality, where we struggle with complex, unstructured and undefined messiness. In this masterclass, we shared a perspective on the character of wicked problems and on the consequences of working on these kind of challenges. Most of the participants recognised the reflexes we have, trying to master or control a wicked problem and come up with a concrete solution.

To give some perspective on how to deal with wickedness, we presented some overall strategies on navigating in wickedness. We suggested to make room for little mistakes (to prevent big ones), invite different perspectives and voices to the table, to be adaptive all along the way, and create time and space for reflection and learning.

The Wicked problems team got positive feed back on the workshop, leading to the idea next time we might dive a bit deeper into this topic and try to apply one or more concrete approaches and tools to navigate around wickedness.

We continue learning and sharing learnings about wickedness in the ASC network. Therefore we are open to work with wicked cases. So, Is your organization a partner of Amsterdam Smart City and do you deal with wicked problems? Let the Wicked Problems know and find out if we can inspire you and find innovative ways to navigate through them together. You can contact Francien who is coordinating this team from the Amsterdam Smart City Baseteam.

In the Wicked problems team are: Dave van Loon (Kennisland), Christiaan Elings (RHDHV), Gijs Diercks (Drift), Giovanni Stijnen (NEMO), Bas Wolfswinkel (Arcadis) en Marije Poel (HvA).

4. Digital social innovation: For the social good (and a moonshot)

The fourth edition in the series Better cities. The Contribution of Digital Technology is about “digital social innovations” and contains ample examples of how people are finding new ways to use digital means to help society thrive and save the environment.

Digitale sociale innovatie – also referred to as smart city 3.0 – is a modest counterweight to the growing dominance and yet lagging promises of 'Big Tech'. It concerns "a type of social and collaborative innovation in which final users and communities collaborate through digital platforms to produce solutions for a wide range of social needs and at a scale that was unimaginable before the rise of Internet-enabled networking platforms."

Digital innovation in Europe has been boosted by the EU project Growing a digital social Innovation ecosystem for Europa (2015 – 2020), in which De Waag Society in Amsterdam participated for the Netherlands. One of the achievements is a database of more than 3000 organizations and companies. It is a pity that this database is no longer kept up to date after the project has expired and – as I have experienced – quickly loses its accuracy.

Many organizations and projects have interconnections, usually around a 'hub'. In addition to the Waag Society, these are for Europe, Nesta, Fondazione Mondo Digitale and the Institute for Network Cultures. These four organizations are also advisors for new projects. Important websites are: digitalsocial.eu(no longer maintained) and the more business-oriented techforgood.

A diversity of perspectives

To get to know the field of digital innovation better, different angles can be used:

• Attention to a diversity of issues such as energy and climate, air and noise pollution, health care and welfare, economy and work, migration, political involvement, affordable housing, social cohesion, education and skills.

• The multitude of tools ranging from open hardware kits for measuring air pollution, devices for recycling plastic, 3D printers, open data, open hardware and open knowledge. Furthermore, social media, crowdsourcing, crowdfunding, big data, machine learning et cetera.

• The variety of project types: Web services, networks, hardware, research, consultancy, campaigns and events, courses and training, education, and research.

• The diverse nature of the organizations involved: NGOs, not-for-profit organizations, citizens' initiatives, educational and research institutions, municipalities and increasingly social enterprises.

Below, these four perspectives are only discussed indirectly via the selected examples. The emphasis is on a fifth angle, namely the diversity of objectives of the organizations and projects involved. At the end of this article, I will consider how municipalities can stimulate digital social innovation. But I start with the question of what the organizations involved have in common.

A common denominator

A number of organizations drew up the Manifesto for Digital Social Innovation in 2017 and identified central values for digital social innovation: Openness and transparency, democracy and decentralization, experimentation and adoption, digital skills, multidisciplinary and sustainability. These give meaning to the three components of the concept of digital social technology:

Social issues

The multitude of themes of projects in the field of digital social innovation has already been mentioned. Within all these themes, the perspective of social inequality, diversity, human dignity, and gender are playing an important role. In urban planning applications, this partly shifts the focus from the physical environment to the social environment: We're pivoting from a focus on technology and IoT and data to a much more human-centered process, in the words of Emily Yates, smart cities director of Philadelphia.

Innovation

Ben Green writes in his book 'The smart enough city': One of the smart city's greatest and most pernicious tricks is that it .... puts innovation on a pedestal by devaluing traditional practices as emblematic of the undesirable dumb city.(p. 142). In digital social, innovation rather refers to implement, experiment, improve and reassemble.

(Digital) technology

Technology is not a neutral toolbox that can be used or misused for all purposes. Again Ben Green: We must ask, what forms of technology are compatible with the kind of society we want to build (p. 99). Current technologies have been shaped by commercial or military objectives. Technologies that contribute to 'the common good' still need to be partly developed. Supporters of digital social innovation emphasize the importance of a robust European open, universal, distributed, privacy-aware and neutral peer-to-peer network as a platform for all forms of digital social innovation.

Objectives and focus

When it comes to the objective or focus, five types of projects can be distinguished: (1) New production techniques (2) participation (3) cooperation (4 raising awareness and (5) striving for open access.

1. New production techniques

A growing group of 'makers' is revolutionizing open design. 3D production tools CAD/CAM software is not expensive or available in fab labs and libraries. Waag Society in Amsterdam is one of the many institutions that host a fab lab. This is used, among other things, to develop several digital social innovations. One example was a $50 3D-printed prosthesis intended for use in developing countries.

2. Participation

Digital technology can allow citizens to participate in decision-making processes on a large scale. In Finland, citizens are allowed to submit proposals to parliament. Open Ministry supports citizens in making an admissible proposal and furthermore in obtaining the minimum required 50,000 votes. Open Ministry is now part of the European D-CENTproject a decentralized social networking platform that has developed tools for large-scale collaboration and decision making across Europe.

3. Collaboration

It is about enabling people to exchange skills, knowledge, food, clothing, housing, but also includes new forms of crowdfunding and financing based on reputation and trust. The sharing economy is becoming an important economic factor. Thousands of alternative payment methods are also in use worldwide. In East Africa, M-PESA (a mobile financial payment system) opens access to secure financial services for nine million people. Goteo is a social network for crowdfunding and collaborative collaboration that contribute to the common good.

4. Awareness

These are tools that seek to use information to change behavior and mobilize collective action. Tyze is a closed and online community for family, friends, neighbors, and care professionals to strengthen mutual involvement around a client and to make appointments, for example for a visit. Safecast is the name of a home-built Geiger counter with which a worldwide community performs radiation measurements and thus helps to increase awareness in radiation and (soon) the presence of particulate matter.

5. Open Access

The open access movement (including open content, standards, licenses, knowledge and digital rights) aims to empower citizens. The CityService Development Kit (CitySDK) is a system that collects open data from governments to make it available uniformly and in real time. CitySDK helps seven European cities to release their data and provides tools to develop digital services. It also helps cities to anticipate the ever-expanding technological possibilities, for example a map showing all 9,866,539 buildings in the Netherlands, shaded by year of construction. Github is a collaborative platform for millions of open software developers, helping to re-decentralize the way code is built, shared, and maintained.

Cities Support

Cities can support organizations pursuing digital social innovations in tackling problems in many ways. Municipalities that want to do this can benefit from the extensive list of examples in the Digital Social Innovation Ideas Bank, An inspirational resource for local governments.

Funding

Direct support through subsidies, buying shares, loans, social impact bonds, but also competitions and matching, whereby the municipality doubles the capital obtained by the organization, for example through crowdfunding. An example of a project financed by the municipality is Amsterdammers, maak je stad.

Cooperation

Involvement in a project, varying from joint responsibility and cost sharing, to material support by making available space and service s, such as in the case Maker Fairs or the Unusual Suspects Festival. Maker Fairs or the Unusual Suspects Festival. Municipalities can also set up and support a project together, such as Cities for Digital Rights. A good example is the hundreds of commons in Bologna, to which the municipality delegates part of its tasks.

Purchasing Policy

Digital social innovation projects have provided a very wide range of useful software in many areas, including improving communication with citizens and their involvement in policy. Consul was first used in Madrid but has made its way to 33 countries and more than 100 cities and businesses and is used by more than 90 million people. In many cases there is also local supply. An alternative is Citizenlab.

Infrastructure

Municipalities should seriously consider setting up or supporting a fab lab. Fab Foundation is helpful in this regard. Another example is the Things Network and the Smart citizen kit.. Both are open tools that enable citizens and entrepreneurs to build an IoT application at low cost. These facilities can also be used to measure noise nuisance, light pollution, or odors with citizens in a neighborhood, without having to install an expensive sensor network.

Skills Training

Municipalities can offer citizens and students targeted programs for training digital skills, or support organizations that can implement them, through a combination of physical and digital means. One of the options is the lie detector program, developed by a non-profit organization that teaches young children to recognize and resist manipulative information on (social) media.

Incubators and accelerators

We mainly find these types of organizations in the world of start-ups, some of which also have a social impact. Targeted guidance programs are also available for young DSI organizations. In the Netherlands this is the Waag Society in Amsterdam. A typical tech for good incubator in the UK is Bethnal Green Ventures. An organization that has also helped the Dutch company Fairphone to grow. In the Netherlands, various startup in residence programs also play a role in the development of DSI organisations.

A digital-social innovative moonshot to gross human happiness

It is sometimes necessary to think ahead and wake up policymakers, putting aside the question of implementation for a while. A good example of this from a digital social innovation perspective is the moonshot that Jan-Willem Wesselink (Future City Foundation), Petra Claessen (BTG/TGG). Michiel van Willigen and Wim Willems (G40) and Leonie van den Beuken (Amsterdam Smart City) have written in the context of 'Missie Nederland' of de Volkskrant. Many DSI organizations can get started with this piece! I'll end with the main points of this:

By 2030...

… not a single Dutch person is digitally literate anymore, instead every Dutch person is digitally skilled.

… every resident of the Netherlands has access to high-quality internet. This means that every home will be connected to fast fixed and mobile internet and every household will be able to purchase devices that allow access. A good laptop is just as important as a good fridge.

… the internet is being used in a new way. Applications (software and hardware) are created from within the users. With the premise that anyone can use them. Programs and the necessary algorithms are written in such a way that they serve society and not the big-tech business community.

… every resident of the Netherlands has a 'self-sovereign identity' with which they can operate and act digitally within the context of their own opportunities.

… new technology has been developed that gives residents and companies the opportunity to think along and decide about and to co-develop and act on the well-being of regions, cities, and villages.

… all Dutch politicians understand digitization and technology.

… the Dutch business community is leading in the development of these solutions.

… all this leads to more well-being and not just more prosperity.

… the internet is ours again.

A more detailed explanation can be found under this link

Stay up to date

Get notified about new updates, opportunities or events that match your interests.